Ethiopia: Evidence of social media blocking and internet censorship

Maria Xynou (OONI), Arturo Filastò (OONI), Amnesty International, Girma Walabuma

2016-12-14

Youth in Addis trying to get Wi-Fi Connection. Credit Addis Fortune Newspaper

Recently we published a post about what appeared to be a possible internet

shutdown in Ethiopia during a wave of ongoing protests by ethnic groups. Today,

in collaboration with Amnesty International we are releasing a report that

includes evidence of recent censorship events during Ethiopia’s political

upheaval.

See the Amharic translation of the report. Translated by Wolete Mariam.

View the pdf version of the report here.

Country: Ethiopia

Probed ISP: EthioNet-AS, ET ( AS24757 )

Censorship method: Deep Packet Inspection (DPI), HTTP response failures, DNS

tampering, TCP injections

OONI tests: Web Connectivity, Vanilla Tor, WhatsApp test, HTTP invalid request

line, HTTP header field manipulation, HTTP Host

Measurement period: 2016-06-15 - 2016-10-07

Key Findings

New OONI data published in this report reveals the following:

WhatsApp was found to be blocked inside Ethiopia.

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology was detected. DPI is technology that

can be bought and deployed on any network, enabling monitoring and filtering of

Internet traffic. This can be useful as part of network management, but it can

also be used for mass surveillance and internet censorship. This finding

suggests that Ethiopia has DPI technology in its possession and is deploying it

for censorship purposes inside the country.

Out of 1,403 different types of URLs that were tested, the types of sites that

consistently presented network anomalies and which were more likely to be

blocked include:

News outlets and online forums

Armed groups and political opposition websites

LGBTI websites

Websites advocating free expression

Circumvention tool websites (including Tor and Psiphon)

The above types of websites mostly presented HTTP response failures, indicating

that they were likely blocked by DPI equipment. Overall, 16 different Ethiopian

news outlets presented signs of censorship, many of which showed evidence of

being blocked prior to the state of emergency declaration.

In the course of this investigation, OONI also sought to verify reports from

Ethiopia of a mobile internet shutdown in October 2016. OONI software tests are

designed to examine the blocking of sites and services, but do not monitor

internet shutdowns as a whole. As such, the organisation referred to third party

data such as Network Diagnostic Test (NDT) measurements and Google transparency

reports, in an attempt to examine whether the reported internet shutdown could

be confirmed.

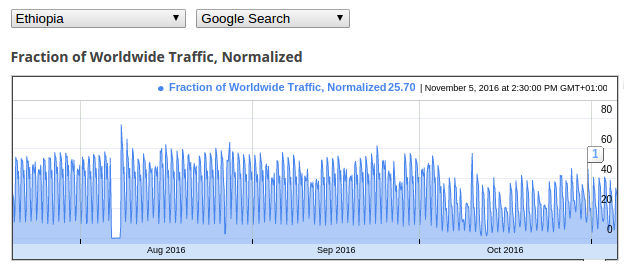

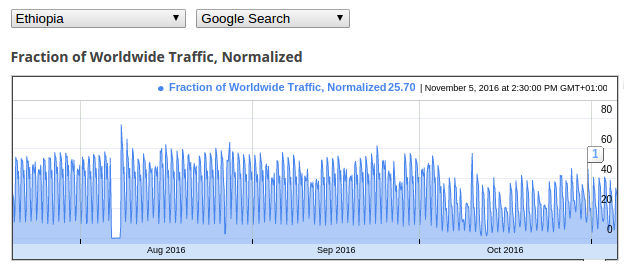

The below graph from Google’s transparency reports illustrates the total volume

of Google Search traffic originating from Ethiopia between July and November

2016. As published in an earlier report by OONI and Strathmore University Centre

for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law (CIPIT), the data shows

a complete drop in Internet traffic in early August, suggesting that a full

Internet block took place following the call by political activists for region-

wide protests on the weekend of 5 and 6 August. While the data shows a decrease

in internet traffic during October, there is no strong indication of an internet

shutdown along the lines of that observed in early August.

Google Transparency Report, Ethiopia, Google Search traffic between July and November 2016.

The findings suggest that if an internet shutdown did occur in October, it only

occurred in some networks in certain locations, rather than nationwide.

Furthermore, the decrease in overall traffic during October could be attributed

to temporary mobile internet shutdowns in certain local networks, or to an

increase of censorship events (for example, targeted blocking of certain

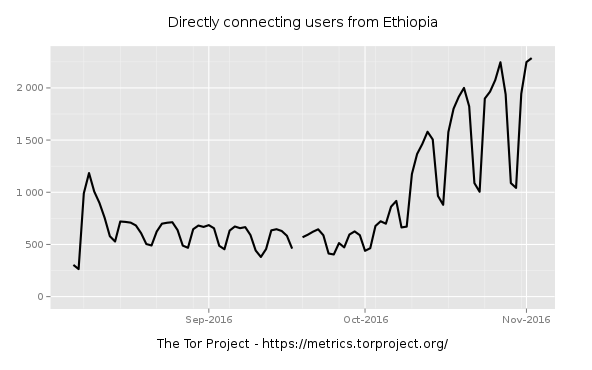

websites and instant messaging services). An examination of data from the

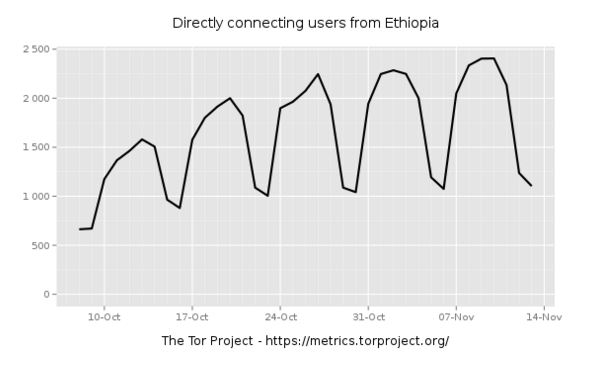

circumvention software Tor, shows a spike in traffic from Ethiopia in October,

suggesting that more people were seeking ways around censorship. This indicates

that there might have been an increase in censorship events following the

declaration of Ethiopia’s state of emergency.

OONI was unable to confirm the reported mobile internet shutdown in October,

partly due to limitations in NDT measurements and Google transparency reports.

We therefore strongly encourage Internet companies including Facebook,

Microsoft, Yahoo and Twitter, to increase transparency around internet traffic

data so that internet shutdowns and other censorship events can be investigated

and verified quickly, and more accurately.

Many of these acts of censorship took place before a state of emergency was

announced, raising questions about whether these measures had any basis in

Ethiopian law, as required by international human rights law. While the State of

Emergency may have subsequently provided a legal framework under Ethiopian law

for some of these measures, the State of Emergency itself is so broadly drafted

that it violates Ethiopia’s international legal obligations and permits

violations of numerous human rights. Amnesty International and OONI are

concerned that unnecessary and disproportionate censorship of the internet will

not only continue during the state of emergency, but become institutionalized

and entrenched.

OONI has unearthed evidence of systematic interference with access to numerous

websites belonging to independent news organizations and political opposition

groups, as well as sites supporting freedom of expression and LGBTI rights. Such

widespread interference and blocking is a violation of people’s freedom of

expression, and specifically, people’s right to hold opinions without

interference, and their right to receive and impart information of all kinds as

guaranteed under article 19 (1) and (2) of the International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Ethiopia has ratified.

Ethiopia’s position on the use of social media indicates that the authorities

are invoking their obligations to restrict freedom of expression where such

freedom is abused, as articulated in article 19 (3) of the ICCPR. However, the

acts of censorship uncovered by OONI’s study are inconsistent with the

requirements laid out in the ICCPR to restrict these rights. Specifically, that

any restrictions will be provided by law and are necessary to respect the rights

or reputations of others; or for the protection of national security or of

public order, public health or morals. Any restrictions to freedom of expression

is subject to a three part test: that they are legal; necessary and

proportional. The acts of censorship evidenced in OONI’s study fail to meet the

test. They are arbitrary, being carried out in the absence of clear and precise

law in the country which governs access to internet and social media,

restrictions/blockade of websites and social media, and clear legal procedures

governing restrictions, including administrative and judicial procedures to

challenge such restrictions and blockades. The acts of censorship also fail the

test of proportionality. The censorship acts uncovered by OONI were not

restricted to specific content; rather the censorship was happening at a large

scale, with dozens of websites and popular communications platforms like

WhatsApp affected over the space of several months.

The decision to restrict people’s ability to receive and impart information by

censoring internet access during the protests, only served to sweep the

underlying issues fuelling the protests under the carpet. To fully address the

situation that led up to the state of emergency, the government must genuinely

commit to addressing the underlying human rights violations that triggered the

protests in the first place; and respect its human rights obligations. This

includes refraining from blocking access to the internet and ensuring that all

its people can enjoy their right to express their opinions; even those who

criticise government policy and action; and guarantee their right to expression

and association online and offline.

Social media companies should make available publicly verifiable data on network

traffic originating from countries around the world, to ensure transparency when

social media restrictions or heavy network disruptions occur.

Executive Summary

Waves of protests against the government have taken place across various parts

of Ethiopia since November 2015. These protests have consistently been quashed

by Ethiopian security forces using excessive, sometimes lethal, force, which led

to scores of injuries and deaths. The crackdown on protests was accompanied by

increasingly severe restrictions on access to information and communications in

large parts of the country by cutting off internet access, slowing down

connections and blocking social media websites.

The protests began on 12 November 2015 in Ginchi, a town in West Shewa Zone of

Oromia Region, against the Addis Ababa Masterplan, a government plan to extend

the capital Addis Ababa’s administrative control into parts of the Oromia. The

protests continued even after the Government announced in January that they had

cancelled the plans, and later expanded into the Amhara region with demands for

an end to arbitrary arrests and ethnic marginalization.

Amnesty International’s research since the protests began revealed that security

forces responded with excessive and lethal force in their efforts to quell the

protests. Amnesty International interviewed at least fifty victims and witnesses

of human rights abuses during the protests, twenty human rights monitors,

activists and legal practitioners within Ethiopia, and also reviewed relevant

other primary and secondary information on the protests and the government

response. Based on this research, the organisation estimates that at least 800

people have been killed since the protests began.

Tensions in Oromia escalated at the beginning of October, following a stampede

during a religious festival which killed at least 55 people. Fresh protests,

some of which turned violent, broke out amidst contestations over who was

responsible for the stampede. Oromo activists blamed security forces for firing

live ammunition and tear gas into the crowds, while the government blamed anti-

peace protestors. The government of Ethiopia declared a state of emergency on 8

October. The state of emergency imposes broad restrictions on a range of human

rights, some of which are non-derogable rights, meaning that under international

law, they may never be restricted, even during a state of emergency.

In addition to using security forces to quash protests, the Ethiopian

authorities have restricted access to internet services during this time.

Amnesty International´s contacts inside Ethiopia reported that social media and

messaging mobile applications such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter, have been

largely inaccessible since early March 2016, especially in the Oromia region

where the bulk of the protests were taking place. Internet services were also

completely blocked in Amhara, Addis Ababa and Oromia Regions following a call by

political activists for region-wide protests on the weekend of 6 and 7 August

2016. The protests went ahead during these two days. The government security

forces used excessive force against the protesters in Addis Ababa, Amhara and

Oromia Regions resulting in the death of at least 100 people.

Internet disruptions started again on 5 October 2016 after protesters in some

parts of Oromia targeted businesses, investments, government buildings and

security forces in the wake of the stampede during the Irrecha thanksgiving

festival in Oromo, which killed at least 55 people. Amnesty International´s

contacts have since reported that internet connections were very slow and social

media services have been inaccessible through browsers. Access to the mobile

internet connection in Addis Ababa improved for a couple of days in early

December, on 4th and 5th, before becoming inaccessible once again.

The Ethiopian government considers that social media has empowered populists and

extremists to exploit people’s genuine concerns and to spread bigotry and hate.

This position was made clear in the Prime Minister’s speech to the UN General

Assembly in September. Indeed, a number of political and other activists have

been arrested and charged under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation on the basis of

their activities on social media platforms. Yonatan Tesfaye, formerly of the

Blue Party, was arrested and charged with terrorism crimes because of his

facebook posts criticizing government policy and action.

In the midst of these protests, and in response to the numerous reports from

Ethiopia that access to the internet was being blocked, the Open Observatory of

Network Interference (OONI) performed a study of internet censorship. OONI is a

free software project whose goal is to increase transparency about internet

censorship and traffic manipulation around the world. OONI undertook the study

in order to assess whether, and to what extent the censorship being reported

actually occurred during the protests. OONI sought evidence of websites and

instant messaging apps were being blocked; systems causing censorship and

traffic manipulation; and inaccessibility of censorship circumvention tools such

as Tor and Psiphon.

OONI’s software tests were run from a computer inside the country (running on

the EthioNet network, the Ethiopia telecom monopoly). Tests were run on a total

of 1,403 different URLs, including both Ethiopian and global websites, in order

to determine website blocking. Additional OONI tests were run to examine whether

systems that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance, and traffic

manipulation were present in the tested network. OONI then processed and

analysed the network data collected based on a set of criteria for detecting

internet censorship and traffic manipulation. The testing period started on 15

June 2016 and concluded on 7 October 2016, immediately prior to the announcement

of the state of emergency.

This report, presents the findings of the OONI study, and Amnesty

International’s human rights analysis of these findings. This report also

provides details of the technical methodology OONI used to verify the blockade

on Whatsapp and the restrictions on websites with political and other content in

a second, distinct section.

Methodology

This report has two distinct sections. Part 1 of the report presents Amnesty

International and OONI´s joint findings related to Internet censorship during

the protests that have rocked Ethiopia since November 2015. Part 2 of the report

provides a detailed overview of OONI´s technical study, including the full range

of tests performed on Ethiopia´s network and acknowledged limitations in the

methodology.

Amnesty International has been documenting the protests since they began, as

well as the state response to the same. Primarily, Amnesty International has

conducted this research remotely, relying on victim and eyewitness testimony,

which has been taken through at least 50 phone and email interviews. Amnesty

International researchers have also used a variety of other primary and

secondary information to corroborate and verify witness accounts of specific

incidents including at least 20 phone and email interviews with human rights

monitors in Ethiopia; members of Ethiopian political opposition parties

including spokespersons; media reports; reports and images posted on social

media; and Ethiopian government communications. Amnesty International has tried

unsuccessfully to engage with the Ethiopian authorities on the protests.

The information gathered by Amnesty International and used in this report, is to

provide the background, and context within which the OONI network measurement

study was carried out. It is not intended to provide comprehensive information

on the human rights violations that have occurred in the context of the

protests. For more information and analysis on the protests, please visit

Amnesty International’s website.

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) is a free software project

that aims to increase transparency about internet censorship and traffic

manipulation around the world. OONI undertook a network measurement study, which

run from 15 June to 7 October 2016. OONI used multiple free and open source

software tests it had designed to examine the following:

Blocking of websites and instant messaging apps.

Detection of systems responsible for censorship and traffic manipulation.

Reachability of circumvention tools (such as Tor, Psiphon, and Lantern) and

sensitive domains.

It is important to note that the technical findings are subject to limitations,

and do not necessarily reflect a comprehensive view of internet censorship in

Ethiopia. The methodology, and its limitations, are discussed in detail in part

2 of the report.

Part 1: Evidence of internet censorship

Background: Sustained protests

Despite the lack of confirmed data about casualties, an estimated 800 people

have been killed due to excessive or otherwise unlawful use of force by the

security forces - some of which may amount to extrajudicial executions - since

the beginning of the protests in November 2015. The United Nations High

Commissioner for Human Rights has described the situation as “extremely

alarming” and urged Ethiopia to allow international human rights observers into

the country. The Ethiopian government, however, rejected this UN request,

arguing that it alone is responsible for the security of its citizens.

There have been almost continuous protests in parts of Ethiopia since November

2015. The protests in Oromia region were initially triggered by plans to extend

the capital, Addis Ababa, into Oromia, but continued even after the Addis Ababa

Masterplan was scrapped in January, evolving into demands for accountability for

human rights violations, ethnic equality and the release of political prisoners.

In August 2016, people in the Amhara Region joined protests against arbitrary

detention of members of the Wolkait Amhara Identity and Self-determination

Committee. The Ethiopian security forces have consistently used excessive, including lethal, force to disperse the protesters. Over 600 protesters in

Oromia and 200 in Amhara have been killed as a result. Hundreds of political

activists, human rights defenders, journalists and protesters have been

arrested. Since the start of the protests in November last year, the police have

charged at least 200 people, including journalists, bloggers and opposition

political party leaders, under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation. Their trials

were ongoing as of November 2016.

Tensions in Oromia escalated again following a stampede during the Irrecha

religious festival on 2 October that resulted in the death of at least 52 people. The cause of the stampede, and the number of casualties, is contested.

The government has claimed that protesters triggered the stampede, while Oromo

activists claim that the government security forces caused the stampede when

they fired tear gas canisters and shot live ammunition into the crowds.

Following the stampede, fresh protests broke out in Oromia with a number of them

turning violent. Protesters attacked foreign and local businesses, farms, and

vehicles, especially those near Addis Ababa.

In response to the wave of protests, the government of Ethiopia severely

restricted internet access and declared a state of emergency on 8 October 2016.

The state of emergency imposes broad restrictions on a variety of human rights,

some of which are non-derogable rights, meaning that under international law,

they may never be restricted, even during a state of emergency. The arrest and

detention of protesters and politically-outspoken individuals critical of

government action continues, including Zone-9 bloggers Natnael Feleke on 4

October and Befeqadu Hailu on 11 November. The government forces also arrested

Anania Sorri and Daniel Shibeshi (members of former Unity Party) and Elias Gebru

(journalist) on 18 November 2016. The three of them had posted their picture

showing the protest sign on 28 October 2016.

The Government of Ethiopia continues to accuse the Ethiopian diaspora based

opposition political parties, Egypt and Eritrea for supporting and fostering the

protests.

Internet censorship during protests

Testimonies gathered by Amnesty International from different parts of the Oromia

region indicate that social media mobile applications such as Facebook,

WhatsApp, and Twitter, were largely inaccessible since early March 2016,

especially in the Oromia region, where residents were waging protests against

the government since November 2015.

”…you can’t use social media apps across Oromia for the last 6 weeks[since Mid-

March]. I personally checked it in Ambo town in West Shawa Zone and In

Batu/Ziway in East Shawa Zone and all [along] the road to there. The blackout is

directed to the apps [both Android and IOS] but, the whole Internet is too slow

and not working at all in some parts of the Region.”

Moreover, the witnesses Amnesty International spoke to in the Oromia region and

neighbouring cities, such as Hawassa, said that not only are the popular social

media applications largely inaccessible, but that the internet has also been

rendered unusually slow.

“All the way to Hawassa from Addis Ababa, I was not able to access skype and

facebook. Even after I reached Hawassa, the connection was too slow that I was

not able to have decent skype conversation during the night.”

The Government blocked access to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Viber during

the National University Exam week “to prevent students being distracted from studying during the exam period and to prevent the spread of false rumours”.

Accordingly, those social media outlets were reportedly inaccessible throughout

the country from 9-14 July 2016.

Internet services were also reportedly not available in Amhara, Addis Ababa and

Oromia Regions following the call for region-wide protests on the weekend of 6

and 7 August 2016. During these two days, the government used excessive,

including lethal force against protesters in Addis Ababa, Amhara and Oromia

Regions resulting in the death of at least 100 people.

Social media and mobile internet was also reportedly unavailable from 5 October

2016 after protests in some parts of Oromia targeted businesses, investments,

government buildings and security forces, during a proclaimed “week of rage”.

In addition, the government employed legislative and judicial tools to

discourage the use of internet and social media for expression of dissenting

views. The government passed a new computer crimes law in June 2016 that among

other things penalises distribution of “violent messages, audio, or video”. The

law also authorizes the Ministry of Justice to issue a warrant for interception

or surveillance, and people suspected of computer crimes can be held in pre-

trial detention for up to four months. The law has had a chilling effect on the

flow of information about human rights violations perpetrated by the security

forces against protesters.

The Ethiopian government has relied on the Anti-terrorism Proclamation (ATP) to

charge and convict people who have criticized government policy and action on

social media platforms. The Ethiopian Government arrested and charged Yonatan

Tesfaye, a political activist and former public relation head of the Blue Party,

with terrorism crimes under the ATP because of the content of his posts on

Facebook. The Zone-9 bloggers and Zelalem Workalemahu et el were also tried

because of their online activities. The Prosecutor charged the Zone-9 bloggers

with terrorism crimes for using encrypted software to ensure the security of

their communications. In Zelalem Workalemahu et al the Court convicted the first

defendant, Zelalem Workalemahu, for provision of training on online encryption

methods.

The Ethiopian Prime Minister´s speech at the United Nations General Assembly in

September 2016, gave an indication of the government’s views around the use of

social media: “social media has certainly empowered populists and other

extremists to exploit people’s genuine concerns and spread their message of hate

and bigotry without any inhibition.”

It is unlikely that social media played a crucial role in mobilizing the

protests, given that internet penetration in the country remains very low at

2.9%. However, it has aided protesters in uncovering acts of violence committed

by the security forces. Previous protests in the country, such as the April 2014 Oromo Protest against the Addis Ababa Master Plan and the Muslim protest against

government interference in religious affairs since 2012 did not attract

international media coverage. However, the current protests in Oromia and Amhara

Regional States have gained a relatively greater media coverage due to the use of social media, even in very small towns, where witnesses have reported on

events and the violence committed by the security forces, sometimes in real-

time. For instance, the footage from the Irrecha tragedy on 2 October 2016 was

available on social media platforms almost in real time.

Google traffic data depicts an acute decline of traffic on 6 and 7 August 2016,

when there was a call by political activists for protests in Addis Ababa,

Oromia, and Amhara. The internet shutdown tallied with the heavy-handed response

of the security forces to the protests on these dates. Since social media was

not accessible on those days in Amhara, Oromia and Addis Ababa there were very

little reports at the time of the violence by the security forces. It was only

after 8 August 2016 that pictures, footage, and reports of excessive force by

security forces started to emerge on social media.

State of emergency

Ethiopia is currently in a state of emergency for six months, as announced by

the government on 8 October 2016.

The Government has arrested more than 11,000 people for “violence and property

damage”. Amongst those in detention are bloggers, journalists, and members of the

political opposition, for publicly criticizing the government, the state of

emergency declaration or for posting the protest sign on Facebook.

Under the state of emergency, all unauthorized protests and assemblies are

banned. Sharing information about protests through social media platforms, such

as Facebook and Twitter, is prohibited, while two TV stations run for the

Ethiopian diaspora, ESAT and the Oromia Media Network, are banned due to their

coverage of the protests.

The state of emergency declaration imposes broad derogations on a variety of

human rights, some of which affect non-derogable rights according to Article 4

(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The

state of emergency declaration established a Command Post chaired by the Prime

Minister with the power to determine the specific restrictions, measures, and

geographic scope in the implementation of the state of emergency.

The Command Post has broad powers, including to:

Prohibit any overt or covert incitement for violence or ethnic conflict, in

whatever form of expression;

Stop or suspend any media;

Prohibit any assembly, association and demonstration;

Arrest anyone suspected of using violence in the areas the Command Post

identifies. Those arrested will be educated and released and, if necessary, they

will be punished under relevant law;

Search and seize any person or place and confiscate where necessary;

Impose curfew;

Block any road or public place or evacuate and move people from certain places;

Evacuate people vulnerable to threats and keep them in safe places for a limited

period of time;

Use proportionate force necessary for the implementation of the state of

emergency;

Accordingly, the Command Post issued a Directive on 15th October, which further

enumerated the acts prohibited, the state of emergency measures, and the

obligations to keep and communicate records. The directive conferred the

security forces with the powers to:

Arrest without warrant;

Detain those arrested at places designated by the Command Post until the end of

the state of emergency;

Search without warrant anytime and anywhere;

Monitor and control any messages through radio, TV, articles, pictures,

photographs, theatre and movies.

Sources told Amnesty International that the security forces have demolished a

number of private satellite frequency receivers in the Oromia and Amhara

regions, barring access to the broadcasts of the Ethiopian Satellite Television

and Oromia Media Network. Several witnesses have also told Amnesty International

that they were unable to access mobile internet service in Oromia, Addis Ababa,

and Amhara Regional States resulting in information blackout on the human rights

situation in those regions. However, it is not clear why the mobile internet was

unavailable.

Findings of the network measurement study

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) performed a study of

internet censorship in Ethiopia in the midst of tensions and ongoing public

protests in Oromia region, and prior to the announcement of the country’s state

of emergency. The aim of this study was to understand whether and to what extent

the censorship being reported actually occurred during the protests, and to

provide evidence in relation to:

Blocking of websites and instant messaging apps

Detection of systems responsible for censorship and traffic manipulation.

Reachability of common circumvention tools used to get around censorship (such

as Tor and Psiphon).

OONI’s software tests were run from a computer inside

the country (running on the EthioNet network, the Ethiopia telecom monopoly).

Tests were run on a total of 1,403 different URLs, including Ethiopian websites

as well as URLs that are commonly accessed around the world. All URLs were

tested for blocking. Other OONI tests were run to examine whether systems that

could be responsible for censorship, surveillance, and traffic manipulation were

present in the tested network. OONI processed and analysed the network

measurement data collected from these tests based on a set of heuristics for

detecting internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

The testing period started on 15 June 2016 and concluded on 7 October,

immediately prior to the announcement of the state of emergency. The testing was

also limited due to security risks to people involved in conducting the testing.

Even though Ethio Telecom is government owned and Ethiopia’s main ISP, it is

likely that censorship was implemented differently across locations, and that

the findings of this study do not necessarily represent nationwide censorship. A

detailed explanation of the methodology, including limitations, can be found in

part 2 of this report.

WhatsApp blocked

OONI has designed a new software test for examining the reachability of

WhatsApp.

This test attempts to perform an HTTP GET request, TCP connection and DNS lookup

to WhatsApp’s endpoints, registration service and web version over the vantage

point of the user. Based on this methodology, WhatsApp’s app is likely blocked

if TCP/IP connections to its endpoints and/or registration service fail, if the

DNS lookup illustrates that different IP addresses have been allocated to its

endpoints, and/or if HTTP requests do not send back a response to OONI’s

servers. Similarly, WhatsApp’s website is likely blocked if any of the above

apply to web.whatsapp.com.

An anonymous researcher ran this test in October from a local vantage point in

Ethiopia (Ethio Telecom) in an attempt to examine whether and how WhatsApp was

censored. The collected measurement data illustrates that while both HTTP and

HTTPS requests to web.whatsapp.com succeeded, HTTPS requests to WhatsApp’s

registration service failed, and so did TCP connections to WhatsApp’s endpoints.

This indicates that WhatsApp’s website was accessible, but its app was blocked.

| web.whatsapp.com | WhatsApp endpoints | WhatsApp registration service |

|---|

| HTTP request | Success | - | - |

| HTTPS request | Success | - | Failed |

| TCP connection | - | Failed | - |

| DNS lookup | Consistent | Consistent | Consistent |

| Result | Accessible | Blocked | Blocked |

Deep Packet Inspection detected

An Ethiopian news website (ecadforum.com) was found to be blocked last month

based on the use of Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology. DPI enables its

users to analyze data packets and protocols. This can be useful as part of

network management, but it can also be used for data mining and internet

censorship.

The blocking of ecadforum.com by DPI equipment was uncovered through OONI’s HTTP host test which was run from a local vantage point in Ethiopia. This test

attempts to examine whether the domain names of websites are blocked, and to

detect the presence of “middle boxes” (software that could potentially be used

for censorship and/or traffic manipulation) in tested networks.

As part of our testing, we performed HTTP requests towards one of OONI’s control

servers. This server is responsive for just sending back any data it receives.

In absence of censorship equipment, we would be able to view OONI Probe’s

request. But when we sent the HTTP Host header containing the domain

“ecadforum.com” to our control server, we noticed that the connections would get

reset. We were only able to receive the control response when requesting a

subdomain of “ecadforum.com” and when we prefixed the request method (GET) with

the newline character. This is summarized in the table below:

| ecadforum.com |

|---|

| Normal GET request | Blocked |

| Modified GET request | Not blocked |

| GET request to subdomain | Not blocked |

| GET request to domain + \t (tab character) | Not blocked |

| Get request to XYZecadforum.comZYX | Not blocked |

This leads us to conclude that the devices implementing this type of

interception were in fact “smart” enough to understand the HTTP protocol and

could only implement blocking when they found the request to match what they

expected to be “valid” HTTP. Therefore, DPI equipment was most likely present in

the tested network and used to implement censorship.

It’s worth pointing out that technology with a similar pattern was previously

found in Turkmenistan in 2013, as reported by OONI.

Websites blocked

Today Ethiopia’s state of emergency imposes restrictions on media. Yet, as part

of our study numerous Ethiopian news outlets presented signs of DNS, HTTP, and TCP/IP blocking prior to the state of emergency declaration.

The table below illustrates the amount and types of network anomalies detected

when testing such sites.

In some cases, we tested different versions of the same sites to examine whether

censorship could potentially be circumvented. Earlier this year, for example, we

found Ugandan ISPs only blocking the HTTP versions of social media sites,

enabling users to access these sites over HTTPS. In this study we therefore

tested various versions of certain sites, such as both the HTTP and HTTPS

versions of oromiamedia.org. In all such cases however, access to these sites

presented signs of network interference, as illustrated in the table above.

Overall, 16 different Ethiopian news outlets presented signs of censorship. As

no block pages were detected, we cannot confirm any censorship events with

absolute certainty. However, the sites that presented the highest amount of

network anomalies are more likely to have actually been blocked, while those

with fewer network anomalies are less likely to have been tampered with. As

such, ecadforum.com - with the highest amount of network anomalies - was most

likely blocked by DPI equipment (as explained previously), while access to it

might have also been interfered with based on DNS tampering. On the other hand,

sites which presented fewer cases of network anomalies (such as satenaw.com) are

less likely to have been blocked, though this remains a possibility.

In any case, it’s interesting to see that out of the 1,403 different URLs (1,217

URLs in the “global list” and 186 URLs in the “Ethiopian list”) that were tested

for censorship as part of this study, access to these 16 Ethiopian news outlets

presented the highest levels of network anomalies, indicating that they were

most likely tampered with. These sites include oromiamedia.org, which is an

independent, nonpartisan, and nonprofit news enterprise that reports on Oromia,

one of the main regions that has been at the heart of the recent wave of

protests and political unrest.

Currently, access to ethsat.com is banned in Ethiopia under the

country’s new state of emergency restrictions. This website is run by the

Ethiopian diaspora, aims to “promote free press, democracy, respect for human

rights and the rule of law in Ethiopia” and also publishes in Amharic. However,

we tested access to this site prior to Ethiopia’s state of emergency declaration

and our findings show that it presented many network anomalies. Similarly to

ecadforum.com, access to ethsat.com presented high levels of HTTP interference,

indicating that it might have also been blocked by DPI equipment before it was

even officially banned.

An Amharic online forum (mereja.com) also presented high levels of HTTP

interference, and was possibly blocked by DPI as well. While the motivation

behind the blocking of news sites could potentially be attributed to the

dissemination of information around the protests, the potential blocking of an

Amharic forum might be attributed to intentions to block communication,

coordination and information dissemination amongst Amharic protesters.

Political opposition and armed groups

As part of our study we found the websites of Ethiopian armed groups and

political opposition groups to be tampered with. In the case of those related to

armed groups espousing violent opposition to the Ethiopian government,

censorship may fall within the permissible restrictions to freedom of expression

under international human rights law.

The table below summarizes our findings:

Ginbot 7 is a national political party and part of Ethiopia’s political

opposition. In 2009 the Ethiopian government accused Ginbot 7 of fostering a

coup attempt to overthrow the government, which Ginbot 7 denied. Ginbot 7 is one

of the proscribed organizations under the Anti-Terrorism Proclamation, which is

potentially why ginbot7.org was blocked. Through our testing we found that

access to this website presented a high amount of network anomalies. In

September 2016 we tested ginbot7.org by sending multiple HTTP GET requests to

access the site. In all cases however, we never received a response.

The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP) is a national political party

which was founded by the Ethiopian diaspora and which is currently headquartered

in the United States. During the 1970s Ethiopia’s then military government

declared open war (“Red Terror” campaign) against the EPRP and other political

opponents, resulting in the death of around 250,000 Ethiopians. Similar to

ginbot7.org, we found eprp.com inaccessible due to HTTP response failures as

part of our testing.

The Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) is a regional political party that was

established by Oromo nationalists in the early 1970s to promote self-

determination, and which was designated as a “terrorist organization” by

Ethiopia’s government. The Ethiopian People’s Patriotic Front (EPPF) is an armed

opposition group in north western Ethiopia that was originally founded to

overthrow the EPRDF regime. As part of our testing, the websites of both groups

appeared to be inaccessible due to HTTP response failures.

Similarly, the websites of two armed opposition groups, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) and the Patriotic Ginbot 7 Movement for Unity and Democracy, also presented HTTP response failures as part of our testing. The

ONLF is an separatist armed group that is fighting for the independence of the

Ogaden region in eastern Ethiopia, bordering with Somalia. An Ogaden news website was also found to be inaccessible, as illustrated in the table of the

previous section of this report.

LGBTI websites

As part of OONI’s testing, access to sites supporting LGBTI rights appeared to

be tampered with since we did not receive HTTP responses when querying them.

These sites, and our research findings, are included in the table below:

The International Foundation for Gender Education (IFGE) is a US-based

educational organization that promotes acceptance for transgender people, while

samesexmarriage.ca is a Canadian site that promotes same-sex marriage. QueerNet

is a project of the Online Policy Group (a non-profit dedicated to online policy

research around digital rights issues) which provides free online services (such

as email hosting, websites, and mailing lists) for LGBTI communities.

Same-sex sexual activity is prohibited in Ethiopia under Article 629 of the

Criminal Code punishable up to fifteen years imprisonment. All three websites

appeared to be inaccessible in September 2016, but appeared to be accessible

when tested again in early October 2016.

Human rights websites

Two sites promoting freedom of speech and expression also presented signs of

network anomalies as part of our study.

Cyber Ethiopia is a Swiss-based non-profit organization that aims to promote

human rights in Ethiopia through programs and policy recommendations that uphold

freedom of speech and expression online. The Free Expression Policy Project is a

think tank on artistic and intellectual freedom. It provides research and

advocacy on free speech, copyright, and media democracy issues.

When querying cyberethiopia.com, we did not receive an HTTP response, indicating

that access to the site was blocked. Our results regarding fepproject.org are

different. When testing the site in June and October 2016, we were able to

successfully connect to it. However, all attempts to establish TCP connections

to the site during August and September 2016 failed and presented timeout

errors. It remains unclear if fepproject.org was intentionally blocked

throughout August and September 2016 based on TCP/IP blocking, or if connections

to the site failed due to transient network failures.

Amongst the many sites that presented HTTP response failures are the sites of

major censorship circumvention tools: Tor and Psiphon.

Tor is a free and open source network designed to provide anonymity to its users

by bouncing their communications across a distributed network of relays, thus

masking their real IP addresses and enabling them to circumvent censorship.

Psiphon is free and open source software that utilizes SSH, VPN, and HTTP proxy

technology to enable its users to circumvent censorship. Ultrasurf is freeware

that utilizes an HTTP proxy server to enable its users to bypass censorship.

Both torproject.org and ultrasurf.us appeared to be inaccessible between June

and October 2016 due to HTTP response failures, while psiphon.ca presented the

same failures from August 2016 onwards. The fact that all three sites presented

HTTP response failures and that http://ultrasurf.us, https://ultrasurf.us and

http://psiphon.ca appeared to be slightly more accessible than

http://www.ultrasurf.us and http://www.psiphon.ca indicate the presence of Deep

Packet Inspection (DPI) equipment in the tested network (as explained in the DPI

section of this report).

While toproject.org was found to be inaccessible, we did not find tor software itself being blocked in Ethiopia during the testing period.

Circumventing censorship

Organizations and companies hosting websites that may be blocked in Ethiopia can

consider hosting their websites on a Tor hidden service to hide its IP address

and prevent blocking. It is also recommended to add HTTPS to your site through

Let’s Encrypt.

Individuals seeking to access blocked websites may consider using the below

circumvention tools and services to get around blocks. Note: Under Anti-

terrorism Proclamation, use of digital security tools have been used in the past

to prosecute bloggers and activists, even if there is no provision of law that

outlaws use of internet security tools, including tor. Yet It is vital that you

understand the security risks in accessing such tools.

Use Tor Browser (or other circumvention tools) to circumvent censorship and

access blocked sites.

If torproject.org is blocked, download Tor Browser here.

If the Tor network is blocked, get Tor bridges to circumvent the blocking and

connect to it.

Use the VPN mode of Orbot to access WhatsApp (and other IM apps) on Android over

the Tor network.

Internet shutdown?

Numerous reports surfaced in October regarding a mobile internet shutdown in

Ethiopia, and this was also reported to Amnesty International by contacts on

the ground.

OONI software tests are designed to examine the blocking of sites and services,

but do not monitor internet shutdowns as a whole. As such, we referred to third

party data such as NDT measurements and Google transparency reports in order to

assess whether we could confirm the reported internet shutdown.

The below graph from Google’s transparency reports illustrates the total volume

of Google Search traffic originating from Ethiopia between July and November

2016. As published in an earlier report by OONI, the data shows a complete drop

in Internet traffic in early August, suggesting that a full Internet block took

place following the call for region-wide protests on the weekend of 5 and 6

August. While the data shows a decrease in internet traffic during October,

there is no strong indication of an internet shutdown along the lines of that

observed in early August.

Google Transparency Report, Ethiopia, Google Search traffic between July and November 2016.

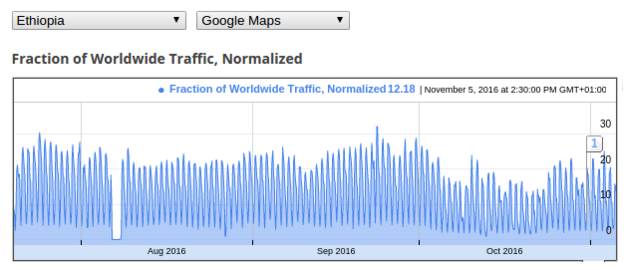

As Google Maps is another Google service that is commonly used via mobile

phones, we also looked at Google Maps traffic originating from Ethiopia between

July and November 2016.

Google Transparency Report, Ethiopia, Google Maps traffic between July and November 2016.

Similar to Google Search traffic, Google Maps traffic appears to be disrupted in

August but not in October. The above graphs indicate that if an internet

shutdown did occur in October, it only occurred in some networks in certain

locations, rather than nationwide. Furthermore, the decrease in overall traffic

during October could be attributed to temporary mobile internet shutdowns in

certain local networks, or to an increase of censorship events (for example,

targeted blocking of certain websites and instant messaging services).

Interestingly, there appears to be a spike in the usage of Tor circumvention software in Ethiopia during October, indicating that internet services might

have been less accessible. This is illustrated via Tor Metrics data below:

The graph below shows an increase in Tor usage from 8th October, when Ethiopia’s

state of emergency was declared.

Tor Metrics data, combined with third party internet traffic data, indicates a

possible increase in censorship events following the declaration of Ethiopia’s state of emergency. While there is no strong indication of an internet shutdown,

it is possible that certain mobile data service might have temporarily been shut

down in certain locations in Ethiopia at specific points in time.

It is worth noting that OONI’s inability to confirm the reported mobile internet

shutdown might also in part be due to limitations in the data sources that we

referred to. We therefore encourage companies (like Facebook) to increase

transparency around internet traffic data so that internet shutdowns and other

censorship events can be studied and evaluated more accurately.

International Human Rights Law

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which

Ethiopia is a state party, guarantees freedom of expression. This includes the “freedom

to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of

frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through

any other media of his choice.” This right is also protected under Article 9 of

the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, to which Ethiopia is a state

party.

Regarding restrictions on access to internet resources, the United Nations Human

Rights Committee has stressed that any restrictions “generally should be

content-specific; generic bans on the operation of certain sites and systems are

not compatible with paragraph 3 of Article 19 of the ICCPR. It is also

inconsistent with paragraph 3 to prohibit a site or an information dissemination

system from publishing material solely on the basis that it may be critical of

the government or the political social system espoused by the government.”

The UN Human Rights Council resolution on the promotion, protection and

enjoyment of human rights on the Internet which was passed on 1 July 2016,

“condemns unequivocally measures to intentionally prevent or disrupt access to

or dissemination of information online in violation of international human

rights law and calls on all States to refrain from and cease such measures.”

The abuse of freedom of expression in the form of propaganda for war, advocacy

of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to

discrimination, hostility or violence may be subject to restrictions under the

ICCPR, but these restrictions must meet three requirements laid out in the

covenant. The first requirement is that restrictions must be provided by law,

which is “formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to

regulate his or her conduct accordingly”. Additionally, “a law may not confer

unfettered discretion for the restriction of freedom of expression on those

charged with its execution.”

The second requirement is that restrictions must be “necessary” to achieve one

of the enumerated legitimate aims under the ICCPR. The third requirement

provides, among other things, that “restrictive measures must conform to the

principle of proportionality… they must be the least intrusive instrument

amongst those which might achieve their protective function.”

OONI’s findings provide evidence of systematic interference with access to

numerous websites belonging to independent news organizations and political

opposition groups, as well as sites supporting freedom of expression and LGBTI

rights. Such widespread interference and blocking is a violation of Ethiopia’s

obligations under article 19 of the ICCPR.

The restrictions on access to information as per the findings of this report

fail to meet the legality test, which is the first requirement under article

19(3). Ethiopia lacks clear and precise law that governs access to internet and

social media, restrictions/blockade of websites and social media, and the legal

procedures. The inventory of Ethiopian relevant telecommunications, cybercrimes,

security, and intelligence laws reveals the absence of provisions that govern

content control and access to internet in the Country. The laws that established

the Information Network Security Agency and the National Intelligence and

Security Service1 authorize neither of the institutions to restrict access to

internet and social media, censor websites for any reason. The Telecom Fraud

Offences Proclamation does not authorize any of the Government agencies to

control and restrict access to internet, websites, or social media application

in the country.

As such, the blocking of WhatsApp and restrictions of certain websites are

arbitrary, being conducted without any specific national law. Moreover, in the

absence of such law, the country also lacks the administrative and judicial

procedures for challenging such restrictions and blockades.

The internet restrictions also fail the proportionality test, because the

interference is not limited to specific content; rather interference is

happening at a very large scale, with dozens of websites affected over the space

of several months. Similarly, blocking access to WhatsApp, a popular

communications platform in Ethiopia is not a justifiable restriction on freedom

of expression and access to information.

Ethiopia’s practices of restricting access to large numbers of websites, as well

as services such as WhatsApp is therefore a clear violation of the rights to

freedom of expression and access to information.

The ICCPR permits derogation from certain rights during emergencies. However,

such derogations must meet several criteria in order to be lawful. Most

importantly, “the situation must amount to a public emergency which threatens

the life of the nation, and the State party must have officially proclaimed a

state of emergency.” Measures taken subject to a derogation must be “limited to

the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation.” The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights does not have a provision that provides for

derogation during emergencies.

The State of Emergency Declaration allows the Command Post to “stop or suspend

any mass media and communications” throughout the country. The geographic

coverage of this measure violates the requirement that derogations under state

of emergency must be limited to exigencies of the situation.

The Ethiopian Government has repeatedly alleged that the violence after the

Irrecha tragedy prompted the declaration of the state of emergency. While the

violence occurred primarily in some districts of Oromia and Amhara, it is

unclear how the exigencies of the situation would strictly require the

imposition of such measures with a geographic scope that covers the whole of the

country.

Conclusion

In the midst of ongoing protests in Ethiopia, access to WhatsApp was found to be blocked, and the covert presence of Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) equipment was

not only unveiled, but it was also found to be filtering access to an

independent Ethiopian media website (ecadforum.com).

Research conducted by OONI between June and October 2016 shows that access to

WhatsApp as well as at least 16 news outlets were blocked prior to the state of

emergency. Also targeted were websites supporting Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual,

Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) rights, organizations advocating freedom of

expression, sites run by opposition groups and armed movements, as well as

websites that offer censorship circumvention tools, such as Tor and Psiphon.

Interestingly, all of these sites consistently presented HTTP response failures

when queried, while the testing of different versions of the same sites appeared

to bypass the filter in certain cases. This pattern is identical to that of

ecadforum.com, indicating that most (if not all) of the above types of sites

were likely filtered by DPI equipment as well.

The Amnesty International research findings during the same period corroborate

OONI’s findings, indicating that other social media applications were very slow,

not working properly or inaccessible, particularly in regions affected by the

protests.

The evidence suggesting that the government is deploying Deep Packet Inspection

(DPI) technology to filter access to internet traffic is concerning. Though it

has many legitimate functions, DPI enables effective surveillance and filtering

of internet traffic, increasing the States’ ability to restrict access to the

internet, fully or partially, on command.

Many of the acts of censorship identified by OONI took place before a state of

emergency was announced, and violated Ethiopia’s obligation to respect, protect

and fulfill its people’s right to receive and impact information. The acts of

censorship, conducted outside a clear legal framework, over several months and

affecting dozens of websites and social media platforms failed to meet the

criteria set out under the ICCPR for restrictions on freedom of expression.

While the State of Emergency may have subsequently provided a legal framework

under Ethiopian law for some of these measures, the State of Emergency itself is

so broadly drafted that it violates Ethiopia’s international legal obligations

and permits violations of numerous human rights. The power the state of

emergency bestows upon the Command post to monitor and suspend all

communications and media throughout Ethiopia is unnecessarily expansive. The

protests and the violence following the protest have been limited to Oromia,

Amhara, Konso District in Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region

(SNNPR) and Addis Ababa.

Amnesty International and OONI are concerned that unnecessary and

disproportionate censorship of the internet will not only continue during the

state of emergency, but become institutionalized and entrenched.

Recommendations

To Ethiopian authorities

Amnesty International and OONI request the Ethiopian government to respect and

protect and fulfill freedom of expression on the internet. Specifically, they

request the Ethiopian Authorities to:

Refrain from blocking access to the internet

Refrain from unlawful censorship of the internet

Ensure that limitations on the right to seek or impart information on the

internet fully adhere to the requirements of article 19(3) of the ICCPR.

Specifically, that the restrictions comply with the three-tier test of legality,

necessity and proportionality, and that they are subject to judicial review.

To social media companies (e.g. Facebook, Twitter)

Make available publicly verifiable data on network traffic originating from

countries around the world, to ensure transparency when social media

restrictions or heavy network disruption occur.

Part 2: Methodology

The methodology of this study, in an attempt to identify potential censorship

events in Ethiopia, included the following:

OONI’s free software tests were run from a local vantage point (EthioNet) in

Ethiopia. Some tests examined two lists of URLs: the one being relevant to Ethiopia, while the other including URLs that are commonly accessed around the

world. All URLs included in these two lists were tested in terms of blocking.

Other OONI tests were run to examine whether systems that could be responsible

for censorship, surveillance, and traffic manipulation were present in the

tested network. Once network measurement data was collected from these tests,

the data was subsequently processed and analyzed based on a set of heuristics

for detecting internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

The testing period started on 15th June 2016 and concluded on 7th October 2016.

Test lists

An important part of identifying censorship is determining which websites to

examine for blocking.

OONI’s software (called OONI Probe) is designed to examine URLs contained in

specific lists (“test lists”) for censorship. By default, OONI Probe examines the

“global test list”, which includes a wide range of internationally relevant

websites, most of which are in English. These websites fall under 30 categories,

ranging from news media, file sharing and culture, to provocative or

objectionable categories, like pornography, political criticism, and hate

speech.

These categories help ensure that a wide range of different types of websites

are tested, and they enable the examination of the impact of censorship events

(for example, if the majority of the websites found to be blocked in a country

fall under the “human rights” category, that may have a bigger impact than other

types of websites being blocked elsewhere). The main reason why objectionable

categories (such as “pornography” and “hate speech”) are included for testing is

because they are more likely to be blocked due to their nature, enabling the

development of heuristics for detecting censorship elsewhere within a country.

In addition to testing the URLs included in the global test list, OONI Probe is

also designed to examine a test list which is specifically created for the

country that the user is running OONI Probe from, if such a list exists. Unlike

the global test list, country-specific test lists include websites that are

relevant and commonly accessed within specific countries, and such websites are

often in local languages. Similarly to the global test list, country-specific

test lists include websites that fall under the same set of 30 categories, as

explained previously.

All test lists are hosted by the Citizen Lab on GitHub, supporting OONI and

other network measurement projects in the creation and maintenance of lists of

URLs to test for censorship. Some criteria for adding URLs to test lists include

the following:

The URLs cover topics of socio-political interest within the country.

The URLs are likely to be blocked because they include sensitive content (i.e.

they touch upon sensitive issues or express political criticism).

The URLs have been blocked in the past.

Users have faced difficulty connecting to those URLs.

The above criteria indicate that such URLs are more likely to be blocked,

enabling the development of heuristics for detecting censorship within a

country. Furthermore, other criteria for adding URLs are reflected in the 30 categories that URLs can fall under. Such categories, for example, can include

file-sharing, human rights, and news media, under which the websites of file-

sharing projects, human rights NGOs and media organizations can be added.

As part of this study, the URLs included in both the Citizen Lab’s test list for Ethiopia and its global list were tested for blocking.

A core limitation to the study is the bias in terms of the URLs that were

selected for testing. The URL selection criteria, for example, included the

following:

Websites that were more likely to be blocked because their content expressed

political criticism.

Websites of organizations that were known to have previously been blocked and

were thus likely to be blocked again.

Websites reporting on human rights restrictions and violations.

The above criteria reflect bias in terms of which URLs were selected for

testing, as one of the core aims of this study was to examine whether and to

what extent websites reflecting criticism were blocked, limiting open dialogue

and access to information across the country. As a result of this bias, it is

important to acknowledge that the findings of this study are only limited to the

websites that were tested, and do not provide a complete view of other

censorship events that may have taken place before and after the testing period.

OONI network measurements

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) is a free software project

that aims to increase transparency about internet censorship and traffic

manipulation around the world. Since 2011, OONI has developed multiple free and open source software tests designed to examine the following:

Blocking of websites.

Blocking of instant messaging apps.

Detection of systems responsible for censorship and traffic manipulation.

Reachability of circumvention tools (such as Tor, Psiphon, and Lantern) and

sensitive domains.

As part of this study, the following OONI software tests were run from a local

vantage point in Ethiopia:

The web connectivity test was run with the aim of examining whether a set of

URLs (included in both the “global test list” and the “Ethiopian test list”)

were blocked during the testing period and if so, how. The HTTP invalid request

line and HTTP header field manipulation tests were run with the aim of examining

whether systems (that could potentially be responsible for censorship and/or

surveillance) were present in the tested network. The HTTP host test was run to

not only examine if tested URLs were blocked, but to also examine whether

specific systems were used in the tested network to implement such blocking.

The sections below document how each of these tests are designed for the purpose

of detecting cases of internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

Web Connectivity

This test examines whether websites are reachable and if they are not, it

attempts to determine whether access to them is blocked through DNS tampering,

TCP connection RST/IP blocking or by a transparent HTTP proxy. Specifically,

this test is designed to perform the following:

Resolver identification

DNS lookup

TCP connect

HTTP GET request

By default, this test performs the above (excluding the first step, which is

performed only over the network of the user) both over a control server and over

the network of the user. If the results from both networks match, then there is

no clear sign of network interference; but if the results are different, the

websites that the user is testing are likely censored. Further information is

provided below, explaining how each step performed under the web connectivity

test works.

1. Resolver identification

The domain name system (DNS) is what is responsible for transforming a host name

(e.g. torproject.org) into an IP address (e.g. 38.229.72.16). Internet Service

Providers (ISPs), amongst others, run DNS resolvers which map IP addresses to

hostnames. In some circumstances though, ISPs map the requested host names to

the wrong IP addresses, which is a form of tampering.

As a first step, the web connectivity test attempts to identify which DNS

resolver is being used by the user. It does so by performing a DNS query to

special domains (such as whoami.akamai.com) which will disclose the IP address

of the resolver.

2. DNS lookup

Once the web connectivity test has identified the DNS resolver of the user, it

then attempts to identify which addresses are mapped to the tested host names by

the resolver. It does so by performing a DNS lookup, which asks the resolver to

disclose which IP addresses are mapped to the tested host names, as well as

which other host names are linked to the tested host names under DNS queries.

3. TCP connect

The web connectivity test will then try to connect to the tested websites by

attempting to establish a TCP session on port 80 (or port 443 for URLs that

begin with HTTPS) for the list of IP addresses that were identified in the

previous step (DNS lookup).

4. HTTP GET request

As the web connectivity test connects to tested websites (through the previous

step), it sends requests through the HTTP protocol to the servers which are

hosting those websites. A server normally responds to an HTTP GET request with

the content of the webpage that is requested.

Comparison of results: Identifying censorship

Once the above steps of the web connectivity test are performed both over a

control server and over the network of the user, the collected results are then

compared with the aim of identifying whether and how tested websites are

tampered with. If the compared results do not match, then there is a sign of

network interference.

Below are the conditions under which the following types of blocking are

identified:

DNS blocking: If the DNS responses (such as the IP addresses mapped to host names) do not

match.

TCP/IP blocking: If a TCP session to connect to websites was not established

over the network of the user.

HTTP blocking: If the HTTP request over the user’s network failed, or the HTTP

status codes don’t match, or all of the following apply:

The body length of compared websites (over the control server and the

network of the user) differs by some percentage

The HTTP headers names do not match

The HTML title tags do not match

It’s important to note, however, that DNS resolvers, such as Google or a local

ISP, often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to them

geographically. Often this is not done with the intent of network tampering, but

merely for the purpose of providing users with localized content or faster

access to websites. As a result, some false positives might arise in OONI

measurements. Other false positives might occur when tested websites serve

different content depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or

in the cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered

with.

HTTP invalid request line

This test tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”)

which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

Instead of sending a normal HTTP request, this test sends an invalid HTTP

request line - containing an invalid HTTP version number, an invalid field count

and a huge request method – to an echo service listening on the standard HTTP

port. An echo service is a very useful debugging and measurement tool, which

simply sends back to the originating source any data it receives. If a middle

box is not present in the network between the user and an echo service, then the

echo service will send the invalid HTTP request line back to the user, exactly

as it received it. In such cases, there is no visible traffic manipulation in

the tested network.

If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, the invalid HTTP

request line will be intercepted by the middle box and this may trigger an error

and that will subsequently be sent back to OONI’s server. Such errors indicate

that software for traffic manipulation is likely placed in the tested network,

though it’s not always clear what that software is. In some cases though,

censorship and/or surveillance vendors can be identified through the error

messages in the received HTTP response. Based on this technique, OONI has

previously detected the use of BlueCoat, Squid and Privoxy proxy technologies in

networks across multiple countries around the world.

It’s important though to note that a false negative could potentially occur in

the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated censorship

and/or surveillance software that is specifically designed to not trigger errors

when receiving invalid HTTP request lines like the ones of this test.

Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of

traffic manipulation, as they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

This test also tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”)

which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

HTTP is a protocol which transfers or exchanges data across the internet. It

does so by handling a client’s request to connect to a server, and a server’s

response to a client’s request. Every time a user connects to a server, the user

(client) sends a request through the HTTP protocol to that server. Such requests

include “HTTP headers”, which transmit various types of information, including

the user’s device operating system and the type of browser that is being used.

If Firefox is used on Windows, for example, the “user agent header” in the HTTP

request will tell the server that a Firefox browser is being used on a Windows

operating system.

This test emulates an HTTP request towards a server, but sends HTTP headers that

have variations in capitalization. In other words, this test sends HTTP requests

which include valid, but non-canonical HTTP headers. Such requests are sent to a

backend control server which sends back any data it receives. If OONI receives

the HTTP headers exactly as they were sent, then there is no visible presence of

a “middle box” in the network that could be responsible for censorship,

surveillance and/or traffic manipulation. If, however, such software is present

in the tested network, it will likely normalize the invalid headers that are

sent or add extra headers.

Depending on whether the HTTP headers that are sent and received from a backend

control server are the same or not, OONI is able to evaluate whether software –

which could be responsible for traffic manipulation – is present in the tested

network.

False negatives, however, could potentially occur in the hypothetical instance

that ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed

to not interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them. Furthermore, the

presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation,

as they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

HTTP Host

This test is designed to examine:

Whether the domain names of websites are blocked;

The presence of “middle boxes” (software that could be responsible for

censorship and/or surveillance) in tested networks;

Whether censorship circumvention techniques are capable of bypassing the

censorship implemented by the “middle box”.

OONI’s HTTP Host test implements a series of techniques which help it evade

getting detected from censors and then uses a list of domain names (such as

bbc.co.uk) to connect to an OONI backend control server, which sends the host

headers of those domain names back to OONI. If a “middle box” is detected

between the network path of the probe and the OONI backend control server, its

fingerprint might be included in the JSON data that OONI receives from the

backend control server. Such data also informs OONI if the tested domain names

are blocked or not, as well as how the censor tried to fingerprint the

censorship of those domains. This can sometimes lead to the identification of

the type of infrastructure being used to implement censorship.

Data analysis

Through its data pipeline, OONI processes all network measurements that it

collects, including the following types of data:

Country code

OONI by default collects the code which corresponds to the country from which

the user is running OONI Probe tests from, by automatically searching for it

based on the user’s IP address through the MaxMind GeoIP database. The

collection of country codes is an important part of OONI’s research, as it

enables OONI to map out global network measurements and to identify where

network interferences take place.

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

OONI by default collects the Autonomous System Number (ASN) which corresponds to