Internet Censorship in Iran: Network Measurement Findings from 2014-2017

Maria Xynou (OONI), Arturo Filastò (OONI), Mahsa Alimardani (ARTICLE 19), Sina Kouhi (ASL19), Kyle Bowen (ASL19), Vmon (ASL19), Amin Sabeti (Small Media)

2017-09-28

Image: Blockpage in Iran

A research study by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI),

ASL19, ARTICLE 19, and Small Media.

Table of contents

Country: Iran

Probed ISPs: AS12660, AS12880, AS16322, AS1756, AS197207, AS197343,

AS198357, AS201150, AS201540, AS202571, AS206639, AS21341, AS25124,

AS29068, AS29256, AS31549, AS34918, AS39074, AS39308, AS39466, AS39501,

AS41881, AS42337, AS43754, AS44208, AS44244, AS44285, AS44498, AS44889,

AS47262, AS47796, AS48159, AS48281, AS48359, AS48434, AS49100, AS49103,

AS49689, AS50530, AS50810, AS51074, AS51119, AS51828, AS56402, AS56503,

AS56687, AS57218, AS57240, AS57563, AS58085, AS58142, AS58224, AS59573,

AS59587, AS59628, AS60054, AS61173, AS61248, AS8571 (60 ISPs in total)

OONI tests: Web Connectivity,

HTTP Invalid Request Line,

HTTP Header Field Manipulation,

Vanilla Tor,

WhatsApp test,

Facebook Messenger test,

Telegram test

Testing period: 22nd September 2014 to 4th September 2017 (3 years)

Censorship method: DNS injection of blockpages, HTTP transparent

proxies serving blockpages

Key Findings

Thousands of OONI Probe network measurements

collected from 60 local networks across Iran over the last three years

have confirmed the blocking of 886 domains (and 1,019 URLs in

total), listed here.

The breadth and scale of internet censorship in Iran is pervasive.

Blocked domains include:

News websites: bbc.co.uk, voanews.com, dw-world.de, arabtimes.com, cbc.ca, reddit.com, russia.tv, aawsat.com, iranshahrnewsagency.com, iranpressnews.com, iranntv.com, tehranreview.net.

Opposition sites: People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, Worker-Communist Party, Labour Party (Toufan), Komala Party of Iranian Kurdistan, National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI).

Pro-democracy sites: National Democratic Institute (NDI), National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Blogs of Iranian political activists: Ali Afshari and Ahmad Batebi.

Human rights sites: Center for Human Rights in Iran, Human Rights & Democracy for Iran, Iran Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, Human Rights Campaign, Human Rights First.

Kurdish sites: kurdistanpress.com, kurdistanmedia.com, Kurdish Human Rights Project.

Baha’i sites: bahai.org, bahai.com,bahai-education.org, bahai-library.com, bahairadio.org.

Women’s rights sites: feminist.com, feminist.org, AWID.

LGBTQI sites: Grindr, lesbian.org, transsexual.org, ILGA.

Sites promoting freedom of expression: Free Expression Network (FEN), Free Speech TV, Committee to Protect Journalists, Freedom House, Reporters Without Borders, ARTICLE 19.

Digital rights groups: ASL19, The Citizen Lab, Herdict, Global Voices, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), The Centre for Democracy and Technology (CDT).

Blogging platforms: wordpress.com, blogger.com, blogspot.com, persianblog.com.

Search engines: google.com, duckduckgo.com.

Communication tools: viber.com, paltalk.com.

Social networks: twitter.com, facebook.com, pinterest.com, myspace.com, 4chan.org.

Media sharing platforms: youtube.com, vimeo.com, instagram.com, netflix.com, flickr.com, metacafe.com.

Anonymity and censorship circumvention tool sites: torproject.org, psiphon.ca, openvpn.net, freenetproject.org, anonymouse.org, anonymizer.com, megaproxy.com, ultrasurf.us, hotspotshield.com.

OONI tests revealed blocking of the Tor network

in many networks across Iran. Some Tor bridges, used to circumvent the

blocking of the Tor network, remained partially accessible.

Facebook Messenger was blocked using DNS manipulation.

In contrast, other popular communications apps, like WhatsApp

and Telegram,

were accessible during the testing period.

Internet censorship in Iran is quite sophisticated. ISPs regularly

block both the HTTP and HTTPS versions of sites by serving blockpages

through DNS injection and through the use of HTTP transparent proxies.

Most ISPs not only block the same sites, but also use a standardized set

of censorship techniques, suggesting a centralized censorship apparatus.

Internet censorship in Iran is non-deterministic. Many observations

flipped between blocking and unblocking sites over time, possibly in an

attempt to make the censorship more subtle.

The government isn’t the only source of censorship in Iran.

Norton

and GraphicRiver

are examples of services inaccessible in the country because they block

IP addresses originating from Iran, in compliance with U.S. export laws and regulations. Virus Total,

which uses Google App Engine (GAE), was likewise inaccessible

because Google blocks access to GAE from Iran.

Introduction

This study is part of an ongoing effort to monitor internet censorship

in Iran and in more than 200 other countries around the

world.

This research report, written by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) in collaboration

with ASL19, ARTICLE 19, and Small Media, presents censorship findings from

the analysis of thousands of network measurements

collected from 60 networks in Iran over the last three years.

The aim of this study is to increase the transparency of information

controls in Iran through the interpretation of empirical

data.

The following sections of this report provide information about Iran’s

network landscape and internet use, its legal environment with respect

to freedom of expression, as well as about cases of censorship that have

previously been reported in the country. The remainder of the report

documents the methodology and key findings of this study.

Background

Network landscape

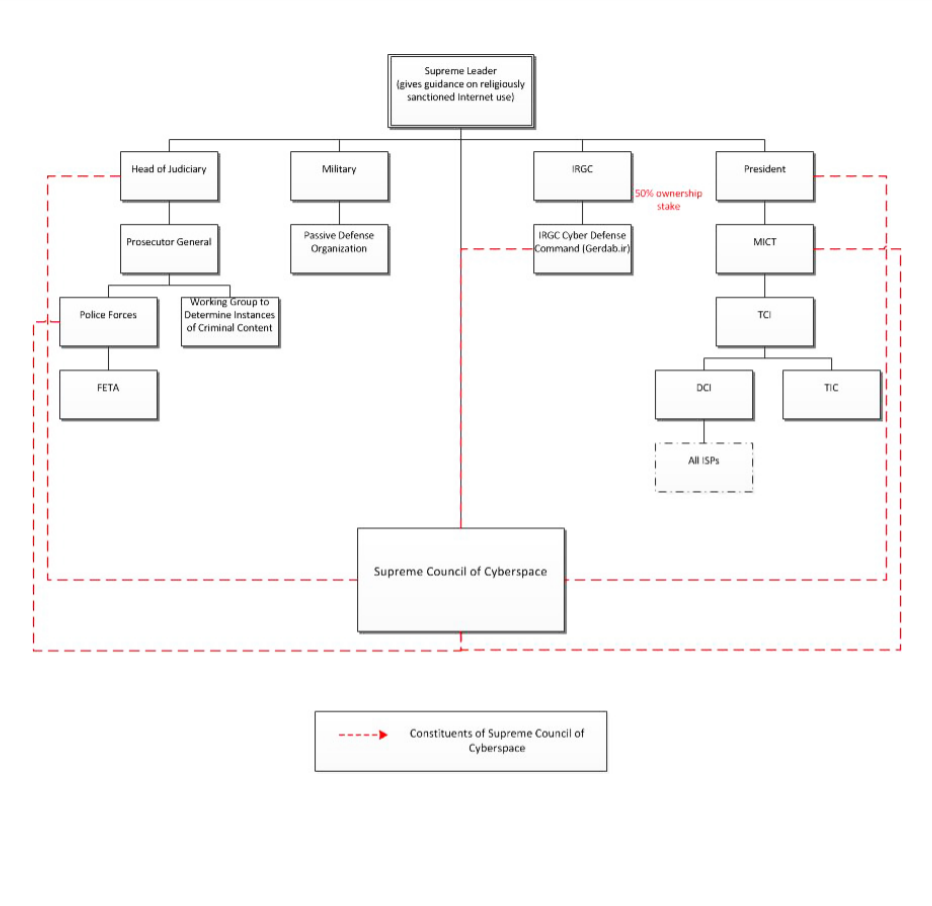

Iran’s internet landscape is characterised by an infrastructure of

control (see page 8-10 of the Open Net Initiative’s (ONI) After the Green Movement

report). The very nature of how Iran connects to the world wide web is

enwrapped in the Islamic Republic’s core institutions.

Internet gateways into Iran are managed by the Telecommunication

Infrastructure Company (TIC) which maintains a monopoly, and is managed

by the Ministry of Information Communications and Technology. The TCI

also owns the Data Communication Company of Iran (DCI), which is the

main ISP of the country. Of greatest concern within this infrastructure

(visualized in the infographic from ONI below) is the fact that a

consortium of private businesses owned by the paramilitary institution

of the Revolutionary Guards

(known for their arrests, surveillance, and repression of human rights

defenders, journalists, bloggers, and internet users exercising their

rights to freedom of expression online) owns about 50% of the shares of

the Telecommunications Company of Iran (which operates the TIC) when the

government attempted to privatize it in 2007.

Source: After the Green Movement: Internet Controls in Iran, 2009-2012,

OpenNet Initiative

This is of great concern as the Revolutionary Guards effectively yield

significant influence over the company that routes all the internet

traffic through the country. As ONI

wrote in

2013, “This single point of connection makes it easy for the government

to control the Internet and effectively filter it either by blocking

webpages or blacklisting keywords.”

Below we include some

observations

on Iran’s ASN infrastructure based on BGP interactions data from

RIPE and

CAIDA.

The following ASes on the border of Iran’s network to rest of the world,

with the first two controlling more than 90% of the connections.

AS48159 - Telecommunication Infrastructure Company

AS12880 - Information Technology Company (ITC)

AS203100 - Iman Samaneh Sepehr LLC

AS62229 - Fars News Agency Cultural Arts Institute

AS39200 - Research Center of Theoretical Physics & Mathematics (IPM)

AS58262 - Nrp Network LLC

AS44932 - Fannavaran-e Idea Pardaz-e Saba PJSC

AS31732 - PARSUN NETWORK SOLUTIONS PTY LTD

AS6736 - Research Center of Theoretical Physics & Mathematics (IPM)

The above ASes are connected to:

AS1299 - TELIANET - Sweden

AS24940 - HETZNER - Germany

AS29049 - Delta Telecom - Azerbaijan

AS200612 - Gulf Bridge International - UAE

AS6453 - Tata Communications - US

AS34984 - Super Online - Turkey

AS1273 - Vodafone Group PLC - UK

AS6762 - Telecom Italia Sparkle S.p.A. - Italy

AS3491 - Beyond The Network America, Inc. US

AS15412 - Flag Telecom Global Internet - UK

AS8529 - Omatel - Oman

AS4436 - nLayer Communications - US

AS3257 - GTT Communications Inc. - Germany

AS33891 - Core Backbone - Germany

AS12212 - Ravand Cybertech Inc. - Canada

AS59456 - Cloud Brokers IT Services GmbH - Austria

AS42926 - Radore Veri Merkezi Hizmetleri- Turkey

AS60068 - Datacamp Limited - CDN77 - UK

The following ASes are acting like an internal hub with more ASes

connected to them but don’t have direct connection to international

networks.

AS51074 - GOSTARESH-E-ERTEBATAT-E MABNA COMPANY (Private Joint Stock)

AS24631 - Tose’h Fanavari Ertebabat Pasargad Arian Co. PJS

AS12880 - Information Technology Company (ITC)

AS44889 - Farhang Azma Communications Company LTD

AS41881 - Fanava Group

AS59587 - PJSC “Fars Telecommunication Company”

The following International ASes import BGP data from Iran’s ASes.

AS198398 - Symphony Solutions FZ-LLC - UAE

AS131284 - Etisalat Afghan - Afghanistan

AS45178 - Roshan AF - Afganistan

AS55330 - Afghanistan Government Communication Network - Afghanistan

AS41152 - Ertebatat Faragostar Sharg Company, PVT. - UAE

AS36344 - Advan Technologies LLC - US

AS25152 - RIPE NCC - Netherlands

AS3177 - Visparad Web Hosting Services LLC - EU

AS47823 - Mohammad Moghaddas - Germany

The above international ASes are connected to the following ASes.

AS16322 - Pars Online PJS

AS48159 - Telecommunication Infrastructure Company

AS25184 - Afranet

AS43754 - Asiatech Data Transfer Inc PLC

AS42337 - Respina Networks & Beyond PJSC

AS31549 - Aria Shatel Company Ltd

Research on Iran’s network infrastructure has revealed the presence of a

“hidden internet”, with private IP

addresses allocated on the country’s national network.

Telecommunications entities were found to allow private addresses to

route domestically, whether intentionally or unintentionally, creating a

hidden network only reachable within Iran. Moreover, the research found

that records such as DNS entries suggest that servers are assigned both

domestic IP addresses and global ones.

Internet use

According to recent statistics

published

in May 2017 by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology

(ICT) , the total number of fixed broadband users in Iran summed up to

10 million users, and the total number of mobile-broadband users summed

up to 41 million users.

ASL19 conducted a survey in December 2016 with a

total sample size of 3,147, including 304 female and 2720 male

participants. Regarding internet usage, survey participants were asked

how frequently they use the internet for different activities. More than

10% of participants reported that they use the internet more than a few

times a day for online education and more than 32% for email and

communications. More than 31% of participants said that they use the

internet a few times a day for work and over 47% said that they use it a

few times a day for reading the news online. ASL19’s survey also asked

participants how frequently they use different social media platforms.

More than 85% of participants said that they use Telegram more than a

few times a day. Almost 6% said they use Facebook, over 8% use Twitter

and 46% said they use Instagram daily.

TechRasa’s recent survey

included 3,707 Iranians between the ages of 18 to 65, with 2,829 men and

878 women. According to their survey, 80% of participants have an

account on Telegram and 50% have an account on Instagram. 20% of

participants reported that they have an account on Facebook, even though

it is

blocked

in Iran. As for the frequency of use of social media and messaging apps,

participants reported that they use Telegram the most (80%), while

Instagram is used more than 40%, Facebook over 10% and Twitter more than

5% as frequently.

Legal environment

This section explores the Iranian laws pertaining to freedom of

expression and the press, via an analysis of three key legal documents:

the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,

the Press Law,

the Penal Code,

Computer Crimes Law.

Additionally, the erosion of freedom of expression can be seen through

the institutionalisation of censorship bodies. Overall, legal

protections for freedom of expression and the press are somewhat

ambiguous: rights are formally enumerated, while the opportunities in

which they may be exercised are restricted. To unpack this tension, we

turn to a few key passages from the Iranian constitution.

The 1979 Constitution of Iran protects the rights to free

expression, peaceful assembly and association in Articles 24, 26, and 27

respectively, but also permits these rights to be curtailed in

circumstances not compatible with the ICCPR. These include very vague

terms that are not defined, enabling arbitrary restrictions on the

exercise of these rights:

Freedom of expression can be restricted if it is found to be

“detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam or the rights

of the public” (Articles 20 and 24);

Article 40 prohibits the exercise of constitutional rights in a

manner deemed to be “injurious to others” or “detrimental to

public interests”;

The preamble of the Constitution specifies that the media must

“strictly refrain from diffusion and propagation of destructive

and anti-Islamic practices”.

The Penal Code (IPC) contains broad provisions criminalising

expression that are against international human rights law; including

criminal insult (see Book Five, Articles 513, 514, 515, 517, 609)

and blasphemy provisions (see Book Two, Part 2, Chapter 5),

criminalisation of disseminating ‘propaganda against the State’ (Book One, Article 286),

spreading false rumours, lies, and creating “anxiety and unease in the

public’s mind” (Book One, Article 286).

Penalties include prison sentences (ranging from 3 months to 5 years),

flogging, and even death. Together with other vague and overbroad

provisions, such as “acting against national security”, “membership in

an illegal organization”, and “participation in an illegal gathering”

(Book Five, Article 502, 505, 507, 510, 511, 512)

these provisions are arbitrarily interpreted to criminalise journalists,

bloggers, human rights defenders and minority groups as well as others

legitimately exercising their rights.

The Press Law: Article 24 of the Constitution protects press

freedom, but not for media deemed “detrimental to the fundamental

principles of Islam or the rights of the public”. Combined with the

repressive Press Law, severe restrictions on media freedom remain the

norm (read more about the Press Law

here).

Examples of problematic provisions of the Press Law include:

Article 2 requires the press to pursue at least one of five

“legitimate objectives”, which include “to campaign against

manifestations of imperialistic culture” and “to propagate and

promote genuine Islamic culture and sound ethical principles”;

Articles 6 prohibits the publishing of an exceptionally broad

spectrum of content including atheistic articles, those

prejudicial to Islamic codes, insulting Islam and/or its

sanctities, offending senior Islamic jurists, those quoting

articles from the “deviant press” or groups which are seen as

opposing Islam, or any publication deemed contradictory to the

Constitution;

In October 2016, President Rouhani’s administration proposed a

new bill

(the ‘Comprehensive Mass Media Regulation’) to replace the current Press

Law that will impose greater restrictions on media freedom. If

introduced, the bill raises concerns as it gives more leeway to judges

and prosecutors to determine whether an offence has been committed,

thereby facilitating the politically motivated judicial harassment of

journalists and newspapers both offline and online.

The Computer Crimes Law: Adopted by the Parliament in January 2010,

the Computer Crimes Law is saturated with provisions that criminalise

legitimate expression in the digital space, including draconian

content-based restrictions designed to allow the State to exert

unfettered control in the sphere where its authority is most frequently

challenged.

Among the content-based restrictions targeting online expression are the

offences against “public morality and chastity” (Articles 14 and 15) and

the “dissemination of lies” (Articles 16 – 18) that are engineered to

ensnare all forms of legitimate expression. These include broad

defamation and obscenity provisions that are antithetical to the right

of freedom of expression. Essential elements of offenses are described

with ambiguity and in vague and overbroad terms, giving the government

unfettered discretion to pursue its own prerogatives above the interests

of the public and the standards set by the international human rights

law.

The Computer Crimes Law mandates severe sentences that penalise

legitimate expression and offend the principle of proportionality,

without defences for individuals acting in the public interest. The

availability of the death penalty (Article 14) for crimes committed

online against public morality and chastity is particularly abhorrent.

Other sanctions include lengthy custodial sentences (Articles 14, 16, 18

and 27), excessive fines (Articles 1, 2, 3, 14, 16, 18 and 21), and

judicial orders to close organisations (Article 20) and ban individuals

from using electronic communications (Article 27). These penalties also

apply to Internet Service Providers that fail to enforce content-based

restrictions (Articles 21 and 23), incentivising the private sector to

promulgate Iran’s censorship culture.

The institutionalisation of online censorship: A number of

regulatory bodies with extremely opaque structures have been founded

since 2009 with mandates to restrict access to and use of the internet.

These bodies can be divided into three tiers: the first constituting

high-level policymaking councils; the second made up of executive

decision-making bodies; and the third including a range of enforcement

agencies.

Policymaking: The principal policymaking body is the Supreme Council

on Cyberspace (SCC), which develops Iran’s domestic and international

cyber policies, with members including Iran’s President and the Head of

the Judiciary. This council is overseen by the Supreme Cultural

Revolution Council (SCRC) which was set up in 1980, and the Supreme

Leader is only person who can overrule their decisions. The SCRC is

dominated by Islamic fundamentalists, based in the city of Qom,

and made up of the clerical elites making strategic decisions

influencing the Supreme Leader. The President of Iran is the ex-officio

chairman of the Council.

Executive decision-making bodies: This tier includes executive

decision-making bodies such as the Committee Charged with Determining

Offensive Content (CCDOC), and the Ministry of Information and Cultural

Guidance (MICG).

The CCDOC identifies sites that carry prohibited content, communicates

the standards to be used in identifying unauthorised websites to the

Telecommunication Company of Iran (TCI), other major ISPs and the

Ministry of Communication and Information Technology and makes website

blocking decisions. The public may ask the CCDOC to block or unblock a

website via an online request form. The final decision will be made by

the Committee. The precise number of blocked websites in Iran is not

publicly available.

In January 2010, the CCDOC issued a “list of Internet offences” which

would lead up to blocking a website. The list is very long and targets a

wide range of areas, including anything that is contrary to “the public

morals and chastity,” “religious values” and “security and social

peace,” and anything that is “hostile towards government officials and

institutions” or which “facilitates the commission of a crime,”

including circumventing censorship or bypassing filtering systems. It

also lists “criminal content in relation to parliamentary and

presidential elections”.

The CCDOC is not independent of the Government but is an arm of the

Executive. It is headed by the Prosecutor General, and its other members

are representatives from 12 governmental bodies. Key members include the

Chief of Police and representatives of the Ministries of: Intelligence;

Islamic Guidance; and Communication and Information Technology.

International standards require that the determination of what content

should be blocked should only be undertaken by a competent judicial

authority or body which is independent of political, commercial or other

unwarranted influences to ensure that blocking is not used as a means of

censorship.

The SCC and the CCDOC also have seven members in common, which allows

for policy diffusion and institutional alignment.

Enforcement agencies: A number of enforcement agencies are

responsible for taking action against offenders. Iran’s Cyber Police

unit (FATA), tasked with fighting “digital criminals”, is the most

notorious. In the chain of command of internet censorship in Iran, FATA

is the policing body that acts on information provided by the SCC and

CCDOC.

Summary

The Iranian Government has developed a centralised system for internet

filtering, created institutions tasked with monitoring Internet use and

censorship of content, engaged the Revolutionary Guard Corps in

enforcing Internet content standards, and entrenched many of these

practices through legislation in the Computer Crimes Law. While certain

rights to freedom of expression are held within the Iranian

constitution, a number of provisions within both the constitution, the

penal code, and the press laws aim to restrict these values based on

vague and often arbitrary principles meant to shield ‘Islam’ or

‘national security’, with very little regard to proportionality.

Reported cases of internet censorship

Iran’s censorship system is one of the most sophisticated in the world.

Over the years, since the introduction of the internet in Iran, the

government has employed different methods to censor it and its

censorship methods have progressively become more complicated. Here we

present a list summarizing the methods that have been employed so far

mainly based on literature review done by TAAP16 and AAH13.

Originally the government delegate the task of censorship to the ISPs to

deploy a IP and keyword based censorship system, moving to a hybrid of

central/ISP based system and eventually after 2009 moving to a central

censorship system. With the popularity of servers hosting multiple sites

and the introduction of CDNs, it moves away from blocking IPs and relies

on censoring host names in HTTP or SNI requests. It also uses throttling

via packet dropping to deter people from services which host a mix of

undesirable and benign content such as Amazon S3 services.

While maintaining mainly a blacklist system, censorship has been more

aggressive during politically sensitive occasions, such as days leading

to organized protests or elections, and engaged in protocol blacklisting

or even white listing. In 2012, for brief period of time, Iran blocked

TLS protocols by identifying the TLS handshake. During the months

leading up to the 2013 presidential election, the censor first throttled

encryption protocols, such as TLS and SSH. During the days leading up to

the election, the censor only whitelisted HTTP protocol and throttled

any other (known or unknown protocol) to the level of dropping after 60

seconds.

Iran also targets censorship circumvention tools. Tor connections, for example, have been

blocked by various methods, including the blocking of the Tor directory

authorities, identifying the DH prime used in Tor TLS handshake,

singling out the TLS certificate validity length etc. Iranian ISPs have

also actively participated in Psiphon client-server negotiation protocol

for receiving new proxy IP addresses and effectively blocking Psiphon’s

proxies. A new law by the Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC) entitled

“Policies and Actions Organizing Social Media Messaging Applications”

(see Article 19’s translation on page 13

here),

created a new legal framework to coerce controls online in the absence

of technical censorship capabilities.

Recent efforts that have been tracked by researchers have followed the

technical and policy implications of the “intelligent filtering”

project. The project was initiated under the Ahmadinejad government with

the intention to unblock a number of currently censored platforms such

as Facebook and Twitter through targeted censorship. However, because of

the difficulties of HTTPS blocking, the project only experienced

technical implementation through Instagram.

Investigations

into the content and type of blocking by Frederic Jacobs and Mahsa

Alimardani eventually led to Instagram enabling HTTPS on its mobile

application (previously only available on the web browser) in order to

limit this type of targeted censorship.

Following the initiation of Instagram encryption across both web based

and mobile application based access, there were some cases of select

images not being accessed in Iran. Preliminary investigations by the

University of Amsterdam’s Digital Methods Initiative

indicated this to be collateral damage from Content Delivery Networks

(CDN) that Instagram shared with it’s parent company, Facebook, which is

blocked in Iran. As of February 2016 however, the government has

announced

they are devoting \$36 million USD to the development of “intelligent

filtering.” According to the New York based human rights NGO Campaign for Human Rights in Iran

(CHRI) there is very “little likelihood of smart filtering capabilities

inside of Iran.”

While technical capabilities for Iranian censorship do not extend beyond

entire platform blocks, Iran’s strongest tactics have been in account

seizures and in attempting to incentivize companies to cooperate with

them. For Telegram, for example, the foremost messaging and social media

application for Iranian users, with over 40 million monthly users

(statistic is from Telegram founder Pavel Durov),

the government has been able to physically takeover certain accounts

through arrests and detentions of the administrators running Telegram

channels. The government has also worked to institutionalize incentives

for platforms such as Telegram to cooperate with the government, as

opposed to implementing technical means to control them. An unsuccessful

ultimatum to all foreign technology companies was given in 2016, which

gave a year to applications such as Telegram to either comply with

authorities, and bring all data for Iranian users into the country (with

possibly government oversight) or face censorship.

Methodology: Measuring internet censorship in Iran

The results of this study are based on a three phase process:

A list of URLs that are relevant and commonly accessed in Iran was

created by the Citizen Lab in 2014 for the purpose of enabling network

measurement researchers to examine accessibility in Iran. As part of

this study, this list of URLs was revised and extended to include

additional URLs. These, along with other URLs

that are commonly accessed around the world, were tested for blocking

using OONI’s free software tests. Tests were run

from local vantage points across Iran. Using the network measurement

data that was collected from these tests, researchers processed and

analyzed this report using a standard set of heuristics for detecting

internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

This study analyzes network measurement data collected from Iran between

22nd September 2014 to 4th September 2017.

Review of the Citizen Lab’s test list for Iran

An important part of identifying censorship is determining which

websites to examine for blocking.

OONI’s software (called

OONI Probe) is designed to examine URLs contained in specific lists

(“test lists”) for censorship. By default, OONI Probe examines the

“global test list”,

which includes a wide range of internationally relevant websites, most

of which are in English. These websites fall under 30 categories,

ranging from news media, file sharing and culture, to provocative or

objectionable categories, like pornography, political criticism, and

hate speech.

These categories ensure that a wide range of different types of websites

are tested. The main reason why objectionable categories (such as

“pornography” and “hate speech”) are included for testing is because

they are more likely to be blocked due to their nature, enabling the

development of heuristics for detecting censorship elsewhere within a

country.

In addition to testing the URLs included in the global test list,

OONI Probe is also designed to examine a test list which is specifically

created for the country that the user is running OONI Probe from, if such

a list exists. Unlike the global test list, country-specific test lists

include websites that are relevant and commonly accessed within specific

countries, often in local languages. Like the global test list,

country-specific test lists are divided into 30 categories.

All test lists are managed by the Citizen Lab on

GitHub. As part of this

study, OONI reviewed the Citizen Lab’s test list for Iran,adding

additional URLs, and updating categorization. Overall, 894 URLs

that are relevant to Iran were tested as part of this study. The URLs

included in the Citizen Lab’s global list

(1,107 unique URLs) were also tested.

It is important to acknowledge that the findings of this study are

limited to the websites that were tested, and do not provide a complete

view of other censorship events that may have occurred during the

testing period.

OONI network measurement testing

Since 2012, OONI has developed multiple free and open source software tests designed to

measure the following:

As part of this study, the following OONI software tests were run in Iran:

The Web Connectivity test checks whether a set of URLs (including both

the “global test list”

and the recently updated “Iranian test list”)

were blocked during the testing period and if so, how. The Vanilla Tor

test was run to examine the reachability of the Tor network, while the WhatsApp, Facebook

Messenger and Telegram tests were run to examine whether these instant

messaging apps were blocked in Iran during the testing period. The

remaining tests check whether “middleboxes” (systems placed in the

network between the user and a control server) that could potentially be

responsible for censorship and/or surveillance were present in the

tested networks.

The sections below document how each of these tests measure internet

censorship and traffic manipulation.

Web Connectivity test

This

test

examines whether websites are reachable and if they are not, it attempts

to determine whether access to them is blocked through DNS tampering,

TCP/IP blocking or by a transparent HTTP proxy. Specifically, this test

is designed to perform the following:

Resolver identification

DNS lookup

TCP connect

HTTP GET request

By default, this test performs the above (excluding the first step,

which is performed only over the network of the user) both over a

control server and over the network of the user. If the results from

both networks match, then there is no clear sign of network

interference; but if the results are different, the websites that the

user is testing are likely censored.

Further information is provided below, explaining how each step

performed under the web connectivity test works.

1. Resolver identification

The domain name system (DNS) is what is responsible for transforming a

host name (e.g. torproject.org) into an IP address (e.g. 38.229.72.16).

Internet Service Providers (ISPs), amongst others, run DNS resolvers

which map IP addresses to hostnames. In some circumstances though, ISPs

map the requested host names to the wrong IP addresses, which is a form

of tampering.

As a first step, the web connectivity test attempts to identify which

DNS resolver is being used by the user. It does so by performing a DNS

query to special domains (such as whoami.akamai.com) which will disclose

the IP address of the resolver.

2. DNS lookup

Once the web connectivity test has identified the DNS resolver of the

user, it then attempts to identify which addresses are mapped to the

tested host names by the resolver. It does so by performing a DNS

lookup, which asks the resolver to disclose which IP addresses are

mapped to the tested host names, as well as which other host names are

linked to the tested host names under DNS queries.

3. TCP connect

The web connectivity test will then try to connect to the tested

websites by attempting to establish a TCP session on port 80 (or port

443 for URLs that begin with HTTPS) for the list of IP addresses that

were identified in the previous step (DNS lookup).

4. HTTP GET request

As the web connectivity test connects to tested websites (through the

previous step), it sends requests through the HTTP protocol to the

servers which are hosting those websites. A server normally responds to

an HTTP GET request with the content of the webpage that is requested.

Comparison of results: Identifying censorship

Once the above steps of the web connectivity test are performed both

over a control server and over the network of the user, the collected

results are then compared with the aim of identifying whether and how

tested websites are tampered with. If the compared results do not

match, then there is a sign of network interference.

Below are the conditions under which the following types of blocking are

identified:

DNS blocking: If the DNS responses (such as the IP addresses mapped to host names) do not match.

TCP/IP blocking: If a TCP session to connect to websites was not established over the network of the user.

HTTP blocking: If the HTTP request over the user’s network failed, or the HTTP status codes don’t match, or all of the following apply:

The body length of compared websites (over the control server

and the network of the user) differs by some percentage

The HTTP headers names do not match

The HTML title tags do not match

It’s important to note, however, that DNS resolvers, such as Google or a

local ISP, often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to

them geographically. Often this is not done with the intent of network

tampering, but merely for the purpose of providing users with localized

content or faster access to websites. As a result, some false positives

might arise in OONI measurements. Other false positives might occur when

tested websites serve different content depending on the country that

the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return

failures even though they are not tampered with.

HTTP Invalid Request Line test

This

test

tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”) which

could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

Instead of sending a normal HTTP request, this test sends an invalid

HTTP request line - containing an invalid HTTP version number, an

invalid field count and a huge request method – to an echo service

listening on the standard HTTP port. An echo service is a very useful

debugging and measurement tool, which simply sends back to the

originating source any data it receives. If a middle box is not present

in the network between the user and an echo service, then the echo

service will send the invalid HTTP request line back to the user,

exactly as it received it. In such cases, there is no visible traffic

manipulation in the tested network.

If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, the invalid

HTTP request line will be intercepted by the middle box and this may

trigger an error and that will subsequently be sent back to OONI’s

server. Such errors indicate that software for traffic manipulation is

likely placed in the tested network, though it’s not always clear what

that software is. In some cases though, censorship and/or surveillance

vendors can be identified through the error messages in the received

HTTP response. Based on this technique, OONI has previously

detected the use

of BlueCoat, Squid and Privoxy proxy technologies in networks across

multiple countries around the world.

It’s important though to note that a false negative could potentially

occur in the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly

sophisticated censorship and/or surveillance software that is

specifically designed to not trigger errors when receiving invalid HTTP

request lines like the ones of this test. Furthermore, the presence of a

middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as

they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

This

test

also tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”)

which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

HTTP is a protocol which transfers or exchanges data across the

internet. It does so by handling a client’s request to connect to a

server, and a server’s response to a client’s request. Every time a user

connects to a server, the user (client) sends a request through the HTTP

protocol to that server. Such requests include “HTTP headers”, which

transmit various types of information, including the user’s device

operating system and the type of browser that is being used. If Firefox

is used on Windows, for example, the “user agent header” in the HTTP

request will tell the server that a Firefox browser is being used on a

Windows operating system.

This test emulates an HTTP request towards a server, but sends HTTP

headers that have variations in capitalization. In other words, this

test sends HTTP requests which include valid, but non-canonical HTTP

headers. Such requests are sent to a backend control server which sends

back any data it receives. If OONI receives the HTTP headers exactly as

they were sent, then there is no visible presence of a “middle box” in

the network that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance

and/or traffic manipulation. If, however, such software is present in

the tested network, it will likely normalize the invalid headers that

are sent or add extra headers.

Depending on whether the HTTP headers that are sent and received from a

backend control server are the same or not, OONI is able to evaluate

whether software – which could be responsible for traffic manipulation –

is present in the tested network.

False negatives, however, could potentially occur in the hypothetical

instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is

specifically designed to not interfere with HTTP headers when it

receives them. Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not

necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as they are often used

in networks for caching purposes.

Vanilla Tor test

This

test

examines the reachability of the Tor

network, which is designed for online

anonymity and censorship circumvention.

The Vanilla Tor test attempts to start a connection to the Tor network.

If the test successfully bootstraps a connection within a predefined

amount of seconds (300 by default), then Tor is considered to be

reachable from the vantage point of the user. But if the test does not

manage to establish a connection, then the Tor network is likely blocked

within the tested network.

WhatsApp test

This

test

is designed to examine the reachability of both WhatsApp’s app and the

WhatsApp web version within a network.

OONI’s WhatsApp test attempts to perform an HTTP GET request, TCP

connection and DNS lookup to WhatsApp’s endpoints, registration service

and web version over the vantage point of the user. Based on this

methodology, WhatsApp’s app is likely blocked if any of the following

apply:

TCP connections to WhatsApp’s endpoints fail;

TCP connections to WhatsApp’s registration service fail;

DNS lookups resolve to IP addresses that are not allocated to

WhatsApp;

HTTP requests to WhatsApp’s registration service do not send back

a response to OONI’s servers.

WhatsApp’s web interface (web.whatsapp.com) is likely if any of the

following apply:

TCP connections to web.whatsapp.com fail;

DNS lookups illustrate that a different IP address has been

allocated to web.whatsapp.com;

HTTP requests to web.whatsapp.com do not send back a consistent

response to OONI’s servers.

Facebook Messenger test

This

test

is designed to examine the reachability of Facebook Messenger within a

tested network.

OONI’s Facebook Messenger test attempts to perform a TCP connection and

DNS lookup to Facebook’s endpoints over the vantage point of the user.

Based on this methodology, Facebook Messenger is likely blocked if one

or both of the following apply:

Telegram test

This

test

is designed to examine the reachability of Telegram’s app and web

version within a tested network.

More specifically, this test attempts to perform an HTTP POST request,

and establish a TCP connection to Telegram’s access points (DCs), as

well as an HTTP GET request to Telegram’s web version (web.telegram.org)

over the vantage point of the user. The test is triggered as blocking

when connections to all access points defined in the

test

fail.

Based on this methodology Telegram’s app is likely blocked if any of

the following apply:

Telegram’s web version is likely blocked if any of the following

apply:

- HTTP(S) GET requests to web.telegram.org do not send back a

consistent response to OONI’s servers.

Data analysis

The OONI data pipeline processes

measurements, including the following types of data:

Country code

OONI by default records the country users are running OONI Probe tests

from, by automatically resolving the user’s IP address with the

MaxMind GeoIP database. The

collection of country codes is an important part of OONI’s research, as

they enable OONI to map out global network measurements and to identify

where network interference takes place.

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

OONI also collects the Autonomous System Number (ASN) which corresponds

to the network or ISP that a user is in. The collection of the ASN is

useful to OONI’s research because it reveals the specific network

provider (such as Vodafone) of a user. This information can increase

transparency in regards to which network providers are implementing

censorship or other forms of network interference.

Date and time of measurements

OONI by default collects the time and date of when tests were run. This

information helps OONI evaluate when network interferences occur and to

compare them across time.

IP addresses and other information

OONI does not deliberately collect or store users’ IP addresses. In

fact, OONI takes measures to remove users’ IP addresses from collected

measurements, to protect its users from potential risks.

However, OONI might unintentionally collect users’ IP addresses and

other potentially personally-identifiable information, if that

information is included in the HTTP headers or other metadata of

measurements. This, for example, can occur if tested websites include

tracking technologies or custom content based on a user’s network

location.

Network measurements

The types of network measurements that OONI collects depend on the types

of tests that are run. Specifications about each OONI test can be viewed

through its git repository,

and collected network measurements can be viewed through OONI Explorer or through

OONI’s measurement API.

OONI processes reports with the aim of deriving meaning from data and,

specifically, to answer the following types of questions:

Which types of OONI tests were run?

In which countries were those tests run?

In which networks were those tests run?

When were tests run?

What types of network interference occurred?

In which countries did network interference occur?

In which networks did network interference occur?

When did network interference occur?

How did network interference occur?

To answer these questions, OONI’s pipeline is designed to process data

which is automatically sent to OONI’s measurement collector. The initial

processing of network measurements enables the following:

Attributing measurements to a specific country.

Attributing measurements to a specific network within a country.

Distinguishing measurements based on the specific tests that were

run for their collection.

Distinguishing between “normal” and “anomalous” measurements (the

latter indicating that a form of network tampering is likely present).

Identifying the type of network interference based on a set of

heuristics for DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and HTTP blocking.

Identifying block pages based on a set of heuristics for

HTTP blocking.

Identifying the presence of “middleboxes” within tested networks.

However, false positives can emerge within the processed data due to a

number of reasons. As explained previously (section on “OONI network

measurements”), DNS resolvers (operated by Google or a local ISP) often

provide users with IP addresses that are closest to them geographically.

While this may appear to be a case of DNS tampering, it is actually done

with the intention of providing users with faster access to websites.

Similarly, false positives may emerge when tested websites serve

different content depending on the country that the user is connecting

from, or in the cases when websites return failures even though they are

not tampered with.

Measurements indicating HTTP or TCP/IP blocking might actually be due to

temporary HTTP or TCP/IP failures, and may not conclusively indicate

network interference. It is therefore important to test the same

websites across time and to cross-correlate data, prior to concluding

that they are in fact being blocked.

Since block pages differ from country to country and sometimes even from

network to network, it can be challenging to accurately identify them.

OONI uses a series of heuristics to decide if a response differs from

the expected control, but these heuristics can fail. For this reason,

OONI only says that there is a confirmed instance of blocking when a

block page is positively detected.

OONI’s methodology for detecting the presence of “middleboxes” - systems

that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and traffic

manipulation - can also present false negatives, if ISPs are using

highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed to not

interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them, or to not trigger

error messages when receiving invalid HTTP request lines. It remains

unclear though if such software is being used. Moreover, it’s important

to note that the presence of a middle box is not necessarily indicative

of censorship or traffic manipulation, as such systems are often used in

networks for caching purposes.

Upon collection of more network measurements, OONI continues to develop

its data analysis heuristics, based on which it attempts to accurately

identify censorship events.

Findings

Thousands of network measurements

collected

from 60 local networks over the last three years reveal pervasive

levels of internet censorship in Iran.

We confirm the blocking of 886 unique domains (and of 1,019 URLs in

total) due to the presence of block pages. Some Iranian ISPs served

block pages through DNS injection, while others used HTTP transparent

proxies to serve block pages.

Internet censorship in Iran does not appear to be deterministic. We

noticed that various ISPs would block sites inconsistently across time,

possibly creating public uncertainty on whether sites were in fact

blocked or not. As such, some of the blocked domains presented in this

study have been blocked and unblocked in various moments across time

over the last three years.

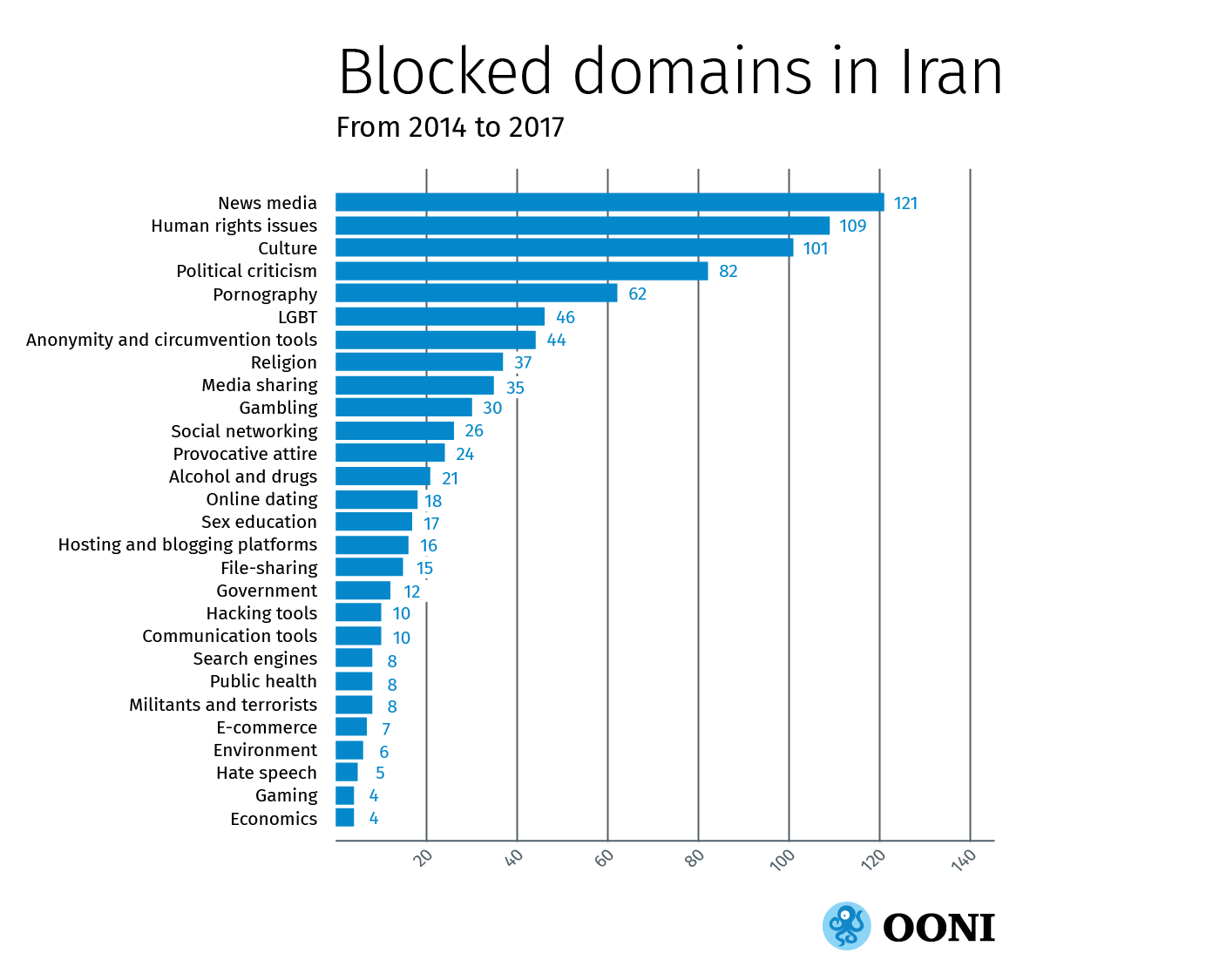

Most of the blocked domains include news outlets and human rights sites,

as illustrated in the graph below.

We have characterised the levels of internet censorship in Iran as

“pervasive” because we found a large portion of content falling under

many categories to be blocked. The above graph illustrates that internet

censorship in Iran is not restricted to illegal forms of content (such

as pornography, gambling, hate speech, alcohol and drugs), but also

extends to a broad range of other types of content, such as news

outlets, human rights sites, blogging platforms, online social networks,

communication tools, anonymity and censorship circumvention tools, and

search engines, amongst others.

Our tests examining the reachability of instant messaging apps revealed

the DNS blocking of Facebook Messenger

in multiple networks across Iran.

WhatsApp

and

Telegram

though were found to be accessible during the testing period. Other

OONI tests

uncovered the presence of middleboxes

across many networks in Iran, which might be responsible for internet

censorship and traffic manipulation.

Circumventing internet censorship in Iran can be quite challenging. We

find that the domains of multiple popular circumvention tool sites (such

as

anonymouse.org

and

psiphon.ca)

are blocked. We

also find that the Tor anonymity network is

blocked

in many networks, as revealed by OONI’s test designed to

measure the reachability to the Tor network. Many Iranian ISPs block

both the HTTP and HTTPS versions of sites, while others even block online translators

as an additional method of limiting circumvention.

Therefore, internet censorship in Iran is not only pervasive in terms of

its breadth, but it is also in how it is implemented. The breadth and

scale of censorship also suggests a high level of surveillance, since

knowing what to block requires prior knowledge of what people are

accessing (or could be accessing).

The government is not the only source of internet censorship in Iran. We

found that

Norton

and

GraphicRiver

are not accessible in Iran because the sites are blocking IP addresses

originating from Iran. Virus Total was also found to be inaccessible,

because it uses Google App Engine, access to which is blocked by Google.

These censorship cases appear to be due to U.S. export laws.

Below, we provide more information on some of the findings of this

study. We encourage researchers to explore the published data for

additional analysis on interesting findings that we have not highlighted

in the following sections.

Blocked domains and tools

The levels of internet censorship in Iran are pervasive since a variety

of different types of sites were found to be blocked, expanding beyond

those that host illegal content. Most of the blocked domains include

news outlets and human rights sites, though the limited amount of sites tested and the bias in

their selection may have influenced this finding. In any case, a wide

range of sites, beyond those that are illegal, were found to be blocked

in the country.

Popular search engines, such as

google.com

and privacy-enhancing

duckduckgo.com,

were amongst those found to be censored. Blogging platforms, like

wordpress.com,

blogger.com,

blogspot.com,

and

persianblog.com

were also blocked. Iranian ISPs even targeted a variety of online gaming

sites, such as World of Warcraft.

While the precise motivation behind this blocking is quite unclear to

us, it might be worth noting that World of Warcraft has been monitored by the NSA

over suspicions that the game was used as a communications platform by

terrorists.

Multiple Israeli domains were found to be blocked. These include

government sites,

news outlets

(haaretz.com),

sports sites

(basket.co.il),

a mail provider

(mail.walla.co.il)

and multiple other types of Israeli sites. The fact that the blocking of

Israeli domains is not limited to those that express criticism towards

the Iranian government or which host illegal content suggests that

Iranian ISPs likely blocked Israeli domains almost indiscriminately,

regardless of their content. The breadth of Israeli domain blocking also

indicates that politics likely influence how information controls are

implemented in Iran. Quite similarly, the blocking of

usaid.gov

and

cia.gov

suggests that the political relations between Iran and the U.S. may have

influenced internet censorship in the country.

We have found many sites to be blocked as part of this study even though

they are no longer active, whether that is because they are censored

(preventing site owners from publishing new content), their servers are

down, or because the domains are squatted.

In the following subsections we highlight some of the blocked sites

and tools. Many more types of domains have also been blocked, all of

which can be found here.

News websites

As part of this study, we found 121 news outlets to be blocked

across Iran over the last three years. These include internationally

popular media sites, as well as Iranian news outlets.

Some of the blocked international news sites include:

Many of the blocked international news outlets express criticism towards

the Iranian government and its regime, likely explaining the motivation

behind their censorship. We also found Reddit, an internationally

popular site that aggregates news and provides a platform for

discussions, to be

blocked

as well.

Iranian ISPs were found to be blocking (at least) five BBC domains:

bbc.co.uk,

bbc.com,

bbcworld.com,

news.bbc.co.uk,

and

bbcpersian.com.

This may not be surprising given that the news agency was previously

banned from reporting in Iran for six years, following its reporting on

unrest in Iran in the aftermath of the 2009 presidential election. The

BBC’s Farsi service was also reportedly blocked

more than ten years ago. More recently, Iranian authorities issued a

court order imposing an asset freeze on 150 Iranian BBC journalists and former contributors

due to their affiliation with the British media organization.

Some Iranian news outlets found to be blocked include:

Iranshahr is the “first news agency for Iranians abroad”. It reports on

international news, but it also has an entire section dedicated to news

from Iran which may be viewed as overly critical towards the Iranian

government, potentially motivating its blocking by local ISPs.

TehranReview serves as a weekly online magazine and a virtual think

tank, which aims to empower the

voices of Iranian citizens, intellectuals and experts. Iran Press News

frequently reports on human rights

issues in Iran. Its English section is edited by Iranian human rights

activist, Banafsheh Zand-Bonazzi,

whose father was a political prisoner until his suicide, which was

viewed as a form of protest

against the government.

All news outlets found to be blocked in Iran can be found here.

Political criticism

Opposition sites, pro-democracy sites and blogs expressing political

criticism were found to be blocked in Iran over the last three years.

Opposition sites

Major opposition sites run by Iranians in exile were found to be

blocked. These include the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran,

a political-militant organization that advocates the violent overthrow

of the Iranian government, as well as the sites of the

Worker-Communist Party

and the Labour Party (Toufan).

The Komala Party of Iranian Kurdistan is a

left-wing Kurdish nationalist political party,

founded

by Kurdish university students in Tehran. Having engaged in armed

struggle for the rights and freedom of the Kurdish people in the 80s and

90s, and having resumed armed struggle more

recently, it is

viewed

by Iranian authorities as a terrorist organization, most likely

explaining the motivation behind the blocking of its site.

Following the Iranian Revolution, the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) was formed in 1981 to act as a parliament in exile

with 530 members, 52% of which are women, including representatives of ethnic and religious minorities. It

aims to establish a

secular democratic republic in Iran, based on the separation of religion

and state. To this end, it has

approved

the National Peace Initiative of the National Council of Resistance of

the Kurdish Autonomy Initiative, the Propagation of the Government

Relations with Religion, and the Plan of Freedom and the Rights of

Women, amongst other initiatives. We found the NCRI’s site to be

blocked

in Iran during the testing period.

Pro-democracy sites

We also found sites advocating for democracy in Iran and internationally

to be blocked.

The National Democratic Institute (NDI) is a non-profit, non-partisan,

non-governmental organization that has supported democratic institutions

and practices around the world since 1983. As part of its work, NDI

collaborates with local partners to promote citizen participation,

strengthen civic and political organizations, and to safeguard

elections. Iran is one of the many countries that NDI works in, having

monitored elections and examined the roles of religious and political institutions. NDI’s site

may have been

blocked

for being viewed as overly

critical,

and possibly for being perceived as interfering in internal affairs

(through election monitoring, for example).

Similarly, we found the site of the National

Endowment for Democracy (NED) to be

blocked

as well. Founded in 1983 by the United States Congress, NED is a

non-profit foundation that also aims to create and strengthen democratic

institutions around the world, including Iran.

NED has supported

projects

in Iran that promote women’s rights, strengthen independent journalism,

monitor human rights violations, and track parliamentary activities,

amongst other projects.

Blogs

Numerous blogs expressing political criticism were found to be blocked

in Iran during the testing period.

These include the blogs of Iranian political activists, such as Ali Afshari

and Ahmad Batebi.

Ali Afshari campaigned for the democratic

reform of Iran, publicly discussing human rights violations and

advocating for freedom, human rights, and democracy. Having published

more than 50 essays and having delivered more than 100 speeches on

topics relating to democracy in Iran, he was

imprisoned

in 2000 and 2003, and spent 400 days in solitary confinement. Ali

Afshari also carried out a research fellowship on “The Challenge of Democratization in Iran”

with the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), whose site was found to be

blocked,

in addition to Ali’s site.

Ahmad Batebi, whose personal site

was found to be

blocked,

was designated a “prisoner of conscience” by Amnesty

International. He was involved in Iran’s student reform movement in the

late 1990s when a fellow student activist was murdered right next to him

by authorities. Once a picture of him holding the student’s shirt splattered in blood appeared

on the cover of The Economist, he received a death sentence for

“creating street unrest”. Following pressure from the international

community, his sentence was commuted to a 15-year prison term, and

eventually reduced to 10 years. While in prison, it was

reported that he was

subjected to torture. Ahmad Batebi eventually fled Iran and was granted

asylum by the United States. He has since worked with the Voice of America (VOA) news agency,

whose site was also found to be

blocked

in Iran.

Other blocked blogs include ghoghnoos.org

which writes about various sensitive topics, such as the Khordad movement, a political faction

in Iran that aims to change the Iranian political system to include more

freedom and democracy. We also found a similar domain,

ghoghnoos-iran.blogspot.com (possibly run by the same blogger, following

the blocking of ghoghnoos.org), to be

blocked

as well. The last post

published on this domain (dated 24th September 2004) discusses the

Pakdasht murders, a case

involving the rape and murder of Afghan refugee children near Pakdasht.

This suggests that the blog may have been blocked right after the last

post was published, which questions the way that authorities handled the

Pakdasht murder case. This finding is particularly interesting because

it indicates that internet censorship in Iran may also be implemented as

a means of hiding government responsibility.

All sites expressing political criticism that were found to be blocked

in Iran can be found here.

Human rights issues

Numerous sites that discuss human rights violations and defend human

rights were found to be blocked in Iran. These include sites specific to

Iran, as well as international human rights sites.

Human rights sites focusing on Iran that were found to be blocked

include the Center for Human Rights in Iran,

Human Rights & Democracy for Iran,

and Iran Human Rights,

amongst others. The Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) is an independent,

nonpartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in the U.S. that aims

to protect and promote human rights in Iran. CHRI has been researching

and documenting human rights violations in Iran since 2008, reaching around 1.5 million people inside Iran every month through

social media. Similarly, Human Rights & Democracy for Iran is a Washington-based project of the

Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation, which “seeks to ensure that human rights in Iran are promoted and protected without discrimination”. As part of

their research and reporting, they have published reports on the

executions of political prisoners in 1988 and on Iran’s 2009 elections.

Iran Human Rights is an Oslo-based non-profit

organization that aims to create an

abolitionist movement in Iran by increasing awareness about the death

penalty. To this end, it has published a number of

reports on executions in Iran.

Some international human rights sites found to be blocked include

Human Rights Watch,

the Human Rights Campaign,

and Human Rights First.

Over the last decades, Iranian authorities have exhibited limited

tolerance when domestic issues are surfaced on the international agenda.

The imprisonment of Ahmad Batebi, an Iranian activist

who brought (more) international attention to human rights violations in

Iran when he appeared on the cover of The Economist, is an example of

this. Human Rights Watch has routinely been

reporting

on human rights violations in Iran, highlighting executions, torture,

and the ill-treatment of minorities, and defending political prisoners

and women’s rights. Therefore, the motivation behind the blocking of

such sites might be attributed to their coverage of incidents that

Iranian authorities may have incentive to conceal, and/or because they

may be viewed as overly critical or inaccurate by authorities.

It’s worth emphasizing though that other major human rights sites - such

as Amnesty International - which also

report on human rights violations in Iran,

were found to be

accessible

in Iran. The fact that Amnesty’s site was found to be accessible is

particularly interesting because the organization has not been permitted to investigate human rights in Iran

over the last decades.

Religious and ethnic minorities

According to international human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch

and Amnesty International,

religious and ethnic minorities in Iran have been victims of

discrimination.

The Kurds are the third largest ethnic group

in Iran. Amnesty has

reported

that while expression of Kurdish culture (such as dress and music) has

generally been respected, the Kurdish minority in Iran continues to

experience deep-rooted discrimination. Since 1918, there has been an

ongoing separatist dispute

between the Kurdish opposition in western Iran and the Iranian

government. Kurdish ethnic rights defenders Farzad Kamangar, Ali

Heydariyan and Farhad Vakili were sentenced to death in 2008,

following what Amnesty

called

a “grossly flawed” judicial process. Many other Kurdish human rights

defenders, community activists and journalists have faced arbitrary arrests and prosecution.

Minority Rights Group International

argues

that the Kurds are amongst the communities at risk in Iran.

As part of this study, we found numerous Kurdish websites to be blocked.

These include Kurdish news outlets, such as

kurdistanpress.com

and

kurdistanmedia.com,

as well as Kurdish human rights sites, such as the Kurdish Human Rights Project.

We also found the site of the Unrepresented Nations & People’s Organization to be

blocked

as well. Given the ongoing tension

with the Kurdish separatist movement and the fact that such sites report

on human rights violations against the Kurds, these censorship events

may attempt to reinforce geopolitical dynamics of power.

Religious minorities have faced discrimination in Iran as well. Iran’s

Baha’i population - the country’s largest religious minority - has

systemically faced prosecution by authorities

over the last century. Following the contested 2009 elections, Human

Rights Watch

argued

that Iranian authorities targeted the Baha’i community as a cover for

the post-election unrest. In late 2016, at least 85 Baha’is were imprisoned

and allegations of torture

surfaced for various other members of the Baha’i community. In addition

to being persecuted for practising their faith, the minority has also

been

discriminated

in terms of education, employment, and inheritance.

As part of this study, we found various Baha’i sites to be blocked.

These include:

Women’s rights

According to Human Rights Watch, women in Iran face

discrimination

in many aspects of their lives, such as marriage, divorce, and

inheritance. Two years ago, authorities even sought to introduce discriminatory laws

that would restrict the employment of women in certain sectors. Amnesty

International has

reported

that Iranian authorities have targeted women human rights defenders,

criminalizing initiatives related to feminism and women’s rights.

Our testing showed the blocking of various sites that defend and promote

women’s rights. These include feminist sites (such as

feminist.com

and

feminist.org),

as well as

AWID,

an international feminist organization

committed to achieving gender equality,

sustainable development and women’s rights. We also found

womeniniran.com to be

blocked,

even though the domain is currently

squatted.

LGBTQI rights

Both male and female homosexual activity is

illegal

in Iran under the country’s sodomy laws. Punishment for engaging in

homosexual activity can result in multiple lashes and, in some cases,

execution.

Several years ago, it was

reported

that an 18-year-old was falsely charged of sodomy and sentenced to

death. Earlier this year, Iranian police arrested more than 30 men

on sodomy charges.

Iranian ISPs were found to be censoring sites connecting LGBTQI

communities, as well as sites promoting LGBTQI rights.

Grindr, an internationally popular social

networking site geared towards gay and bisexual men, was amongst those

found to be

blocked.

One of the first major sites for lesbians

was also

blocked.

We found sites like ILGA, a worldwide federation campaigning for LGBTI rights since 1978, to be

blocked

as well.

While transexuality can be

legal

in Iran if accompanied by a gender confirmation surgery, transsexuals

still experience social intolerance, similarly to many other countries

around the world. This is also suggested by our findings, which show

that sites on transsexuality were amongst

those

blocked

in Iran.

Freedom of expression

Multiple sites promoting freedom of expression were found to be blocked

in Iran. These include the Free Expression Network (FEN),

an alliance of organizations

dedicated to combating censorship

and defending the right to free expression, as well as Free Speech TV,

a U.S-based, independent news network

committed to advancing

progressive social change. We also found the site of the Committee to

Project Journalists to be

blocked

as well.

Many sites run by international, non-profit, digital rights

organizations were amongst those censored in Iran. These include:

Freedom House: An independent watchdog organization that conducts research

and advocacy on democracy, political freedom, and human rights for

most countries around the world (including

Iran). It also monitors censorship, intimidation and violence against journalists, and public access to information. Both the HTTP

and HTTPS

versions of Freedom House’s site were found to be blocked.

Reporters Without Borders: An international non-profit, non-governmental organization headquartered in Paris that promotes and defends freedom of information and freedom of the press. Its mission includes combating censorship and laws aimed at restricting freedom of expression. Both the

HTTP

and HTTPS versions of Reporters Without Borders’ site were found to be blocked.

ARTICLE 19: An international non-profit, non-governmental organization defending freedom of expression. In collaboration with 90 partners worldwide, ARTICLE 19 carries out research and advocacy in support of

free expression. Both the HTTP

and HTTPS

versions of ARTICLE 19’s site were found to be blocked.

ASL19: An independent technology

group connected to both Iranians and technology actors in the West that aims to support civil society goals. To this end, ASL19 helps Iranians bypass internet censorship and more recently started providing support for circumvention tools in the broader Middle East and North

Africa region. The HTTPS version of ASL19’s site was found to be blocked,

but it remains unknown if the HTTP version is blocked as well because it hasn’t been tested (though the blocking of the HTTPS

version strongly suggests that the HTTP version is likely blocked as well).

The Citizen Lab: An interdisciplinary laboratory based at the University of Toronto, focusing on research, development, and high-level strategic policy and legal engagement at the intersection of information and communication technologies, human rights, and global security. The Citizen Lab is known internationally for having published numerous research reports exposing internet censorship and targeted malware attacks against civil

society members. Both the HTTP and HTTPS

versions of The Citizen Lab’s site were found to be blocked.

Herdict: A project under Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society which collects and disseminates real-time, crowdsourced information about internet filtering, denial of

service attacks, and other blockages. Both the HTTP

and HTTPS versions of Herdict’s site were found to be blocked.

Global Voices: An international community of writers, bloggers, and digital activists that translate and report on what is being said in citizen media worldwide. It started off as a project of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society and became an independent non-profit in 2008. Global Voices is known for its advocacy and reporting on digital rights issues, such as surveillance and internet censorship. The blocking of Global Voices appears to be limited to the HTTP version of the site. Our measurements show that while the HTTPS version of the site was accessible in Iran, block pages were served for the HTTP version.

Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF): The leading non-profit organization defending civil liberties in the digital world. EFF champions user privacy, free expression, and innovation through impact litigation, policy analysis, grassroots activism, and technology development. Both the HTTP and HTTPS versions of the EFF’s site were found to be blocked.

The Centre for Democracy and Technology (CDT): An international non-profit organization that defends online civil liberties and human rights, driving policy outcomes to keep the internet open, innovative, and free. Both the HTTP and HTTPS versions of CDT’s site were found to be blocked.

Freedom of expression though also appears to be limited in Iran through

the blocking of popular blogging platforms, such as

wordpress.com,

blogger.com,

blogspot.com,

and

persianblog.com.

All human rights sites found to be blocked in Iran can be viewed here.

Facebook Messenger was found to be blocked in Iran by means of DNS tampering.

This was revealed by OONI’s Facebook Messenger test, which

is designed to examine the reachability of the app by attempting to

perform a TCP connection and DNS lookup to Facebook’s endpoints over the

vantage point of the user. While the test was able to establish TCP

connections to Facebook’s endpoints, DNS lookups to domains associated

to Facebook did not resolve to IP addresses allocated to Facebook,

illustrating that the app was blocked in Iran during the testing period.