The State of Internet Censorship in Venezuela

Mariengracia Chirinos (IPYS Venezuela), Andrés Azpúrua (Venezuela Inteligente / VEsinFiltro), Leonid Evdokimov (OONI), Maria Xynou (OONI)

2018-08-16

A study by IPYS Venezuela, Venezuela Inteligente, and the Open

Observatory of Network Interference (OONI).

Update (2018-10-19): The section on Tor becoming accessible was added.

Probed ISPs: Most recent measurements collected from Digitel

(AS264731), CANTV (AS8048), Movistar (AS6306) and Movilnet (AS27889).

OONI tests: Web Connectivity

test, HTTP Invalid Request Line

test, HTTP Header Field Manipulation

test, WhatsApp test,

Facebook Messenger

test, Telegram test,

Vanilla Tor test,

Tor Bridge Reachability

test

Testing/analysis period: 20th February 2014 to 10th August 2018

Censorship methods: DNS tampering & HTTP blocking

Key Findings

Media censorship appears to be quite pervasive, as a number of

independent media websites were found to be blocked in Venezuela

(primarily) by means of DNS tampering. Blocked news outlets include El Pitazo

and El Nacional,

while La Patilla was temporarily blocked

in June 2018.

Walkie-talkie app Zello was reportedly blocked

during Venezuela’s 2014 protests and recent measurements suggest that

the service remains blocked

by state-owned CANTV. Other blocked sites include a number of currency exchange sites,

as well as

blogs

expressing political criticism.

Censorship circumvention has (possibly) become harder in Venezuela, as

CANTV

blocked

access to the Tor network and to public

obfs4

bridges two months ago.

Introduction

Media censorship was

reported

by Venezuelan civil society groups, IPYS Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente, back in early 2016. At the

time, they measured the blocking of websites across four states in

Venezuela through the use of OONI Probe, which is free and open source software designed

to measure internet censorship. They collected network measurement data

showing the DNS blocking

of numerous local media sites and other types of websites during

Venezuela’s 2015 parliamentary elections. Now, OONI has joined forces

with IPYS Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente.

The Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), IPYS Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente collaborated on a joint

research study to examine internet censorship in Venezuela. Our study

involves the analysis of hundreds of thousands of network measurements collected from

multiple local vantage points over the last four years.

The following sections of this report provide information about

Venezuela’s political and legal environment (with respect to censorship

and freedom of expression) and about previous cases of censorship that

have been reported in the country. The remainder of the report documents

the methodology and findings of our study.

Background

Political environment

Democratic freedoms have

deteriorated

in Venezuela. The government has been characterized as an authoritarian

regime, closing spaces for public discussions and free expression, while

systematic violations of human rights have intensified. According to

IPYS Venezuela, the elections held in

Venezuela in recent years have suffered from a lack of fair conditions.

The institutionality and the State of Rights have been broken, given the

lack of autonomy and independence of the public powers, all dominated by

the strength of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, which has

accompanied Hugo Chávez and currently maintains Nicolás Maduro.

Venezuela is experiencing a complex humanitarian emergency, intensified

by

hyperinflation,

the absence of transparency in public management, and the

weakness

of democratic institutions. These conditions have negatively impacted

the quality of life of citizens, as well as the conditions for the

protection of human rights. Within this context, Venezuelans have been

deprived of the right to decent housing and have very limited access to

public services.

Between January to July 2018, reporting on the transportation crisis,

power outages,

water shortages

and gas shortages

has increased. According to data provided by the Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict (OVCS) and the

Venezuelan Program of Education-Action in Human Rights (Provea), these issues affect the

quality of life of Venezuelans and their ability to exercise their basic

rights.

Internet blackouts in Venezuela have been documented by the Press and Society Institute of Venezuela (IPYS Venezuela), which have left citizens in

rural, suburban and urban areas of the country without internet

connectivity. According to IPYS Venezuela, these internet blackouts have

harmed citizens’ rights to access information and freedom of expression.

Freedom House scores Venezuela 6⁄25 in obstacles to access the internet

(where a lower ranking is worse).

Research conducted by Mariengracia Chirinos in terms of public policies

on internet access reveals that, between 2007 to 2017, a vision of

political and social control prevailed in Venezuela, in favor of the

defense of national sovereignty and the “defense of the country”. This

however, she notes, contradicts the principles of inclusion, diversity,

openness, competitiveness and freedom that should guide the process of

formulating internet access policies.

Public policies around internet access have been limited by regulatory

processes (which follow the model of a closed society), affecting market

competitiveness and incentives for investment. This has had a negative

impact on technological advancements in the telecommunications sector,

which are far from the standards of ECLAC (2016)

and the OECD (2016).

Between 2017 to 2018, this contributed towards connectivity issues

across Venezuela.

IPYS Venezuela

reports that

digital rights were at risk throughout 2017 in light of several

restrictive regulations. Police persecution manifested through arbitrary

arrests of citizens based on their opinions expressed online through

social networks, various portals of digital media and civil society

organizations were attacked, and web portals were selectively blocked.

Threats have been made against journalists, while official structures

for online surveillance and police monitoring have been proposed.

Legal environment

A restrictive framework for expression on the internet was consolidated

in 2017 and internet censorship was legalized. Following a wave of

street protests, the President of the Republic, Nicolás Maduro, signed a decree

to extend the State of Emergency Exception and Economic Emergency, which

further expands internet censorship powers to avoid “destabilization

campaigns”.

The turning point came with the approval of the Anti-Hate law.

Last November, the National Constituent Assembly (ANC) - a body created

outside of the national constitution and which functions as a

“superpower” with all of the ruling parliamentarians - approved the “Law

against Hatred, for Peaceful Co-existence and Tolerance”.

This regulation empowers authorities to block websites

that are deemed to spread hate or incite violence. If messages that are

considered to “incite hatred” are not removed by website owners within 6

hours, they may be subjected to a fine. The law also includes prison

sentences, ranging from 10 to 20 years, for those who do not comply with

censorship requests by authorities.

Similarly, Article 27 of the

Law on Social Responsibility in Radio, Television and Electronic Media

sets conditions for the prohibition of content that does not acknowledge

the legitimacy of authorities or which fosters citizen anxiety.

Reported cases of internet censorship

Pervasive levels of internet censorship have been carried out in

Venezuela since 2014, largely monitored and documented by local civil

society groups IPYS Venezuela and

Venezuela Inteligente.

Their

study

(between 2015 and 2016) showed that 43 websites were systematically

blocked by one or more Venezuelan ISPs. The types of websites that

appeared to be blocked the most include: Sites related to the parallel

market of the dollar (44%), media (19%), blogs criticizing Chavez (12%),

games of chance and online bets (9%), collaboration tools or shorteners

(5%), personal communication tools (5%), gore (2%), anonymization and

circumvention sites (2%), and hosting services (2%).

Movistar was found to block sites the most,

with 41 blocked domains, corresponding to 35 different websites. The

types of sites blocked by Movistar - but which weren’t blocked by

CANTV - include: parallel dollar market, chavismo criticism blogs,

hosting services, collaboration tools or shorteners, and digital media.

Data presented in August 2017 by

Venezuela Inteligente, as follow-up to their previous study with IPYS

Venezuela,

shows that

of the blocked sites, 36% of them were related to currency exchange

rates, 32% were media, 16% games of chance and online bets, 12% social

networking or communications tools, and 4% of them were blogs critical

of the government.

24% of all

blocked sites were international with international audiences, while

76% of them

had (mostly) local audiences.

Between 2017 to 2018, IPYS Venezuela

documented seven

cases of internet censorship, involving news websites, currency exchange

websites and other sites discussing corruption and economic information.

Today, these seven news portals remain blocked by CANTV, Movistar and

Digitel, according to OONI Probe network measurement data collected by IPYS

Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente.

Last year, Venezuela Inteligente

reported,

through the VEsinFiltro project, how three private online streaming

broadcasters - Vivoplay,

VPI, and Capitolio TV (site now

defunct) - were blocked simultaneously by all major ISPs (primarily by

means of DNS) as a result of broadcasting live street protests. VPI and

Capitolio TV resorted to livestreaming on YouTube, instead of on their

own sites, to circumvent the block. The Maduradas portal was also

blocked

by means of DNS.

Media websites blocked in 2018 include El Pitazo,

El Nacional and La Patilla.

These censorship events were (temporarily) implemented by both private

and state providers, who blocked the sites at their own discretion

without a court order, violating due process. These media outlets were

blocked by means of DNS tampering and HTTP blocking, primarily by CANTV,

Movistar, Movilnet, and Digitel.

Authorities of the National Telecommunications Commission have

previously ordered the blocking of websites that disseminate

“destabilizing” information or form a “media war” against the

government. However, no court order or other legal justification was

provided for the censorship events that occurred over the last year.

Furthermore, the National Telecommunications Commission has repeatedly

ignored public information requests

regarding recent internet censorship events.

Methodology: Measuring internet censorship in Venezuela

To measure internet censorship in Venezuela, we ran OONI’s network

measurement software (OONI Probe) on a daily basis across

multiple local vantage points. OONI Probe is free and open source software designed to

measure various forms of network interference.

The main OONI Probe tests that we ran as part of this study include:

OONI’s Web Connectivity test is

designed to measure whether websites are blocked by means of DNS

tampering, TCP/IP blocking, or by an HTTP transparent proxy. This test

is automatically performed both over the vantage point of the user and

from a non-censored control vantage point. If the results from both

vantage points match, then the tested website is most likely accessible.

If the results however differ, then the measurement is flagged as

anomalous. OONI’s current methodology only confirms the blocking of a

website if a blockpage is served. In cases where ISPs do not serve

blockpages, the relevant network measurements are analyzed over time,

examining whether the specific types of failures persist and what causes

these failures (i.e. ruling out false positives).

The testing was mostly limited to the URLs included in the Citizen Lab’s

global

and

Venezuelan

test lists. These lists consist of a variety of different types of URLs

that fall under 30 categories

and that are tested for censorship by network measurement projects like

OONI. Throughout the course of this research, we updated the

Venezuelan test list

to ensure that reportedly blocked sites were being tested. Overall,

around 1,410 URLs, included in both the Citizen Lab’s

global

and

Venezuelan

test lists, were measured as part of this study.

In an attempt to identify which equipment was used to implement internet

censorship in Venezuela, we ran OONI’s HTTP Invalid Request Line

and HTTP Header Field Manipulation

tests. Both tests are designed to measure networks with the aim of

identifying the presence of middleboxes.

OONI’s HTTP Invalid Request Line test does this by sending an invalid

HTTP request line to an echo server listening on the standard HTTP port.

If a middlebox is present, the invalid HTTP request line will be

intercepted by the middlebox, potentially triggering an error that will

be sent back to OONI servers. In the past, this has enabled the

identification of censorship equipment in various

countries around the world. OONI’s HTTP Header Field Manipulation test,

on the other hand, attempts to identify middleboxes by sending HTTP

requests with non-canonical HTTP headers. If a middlebox is present, it

will likely normalize the headers or add extra headers, enabling the

identification of its presence in the network. In addition to OONI Probe

tests, we also performed additional network measurement tests via

Raspberry Pi deployments in Venezuela.

To monitor the accessibility of popular instant messaging platforms over

time, we ran OONI’s

WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger,

and Telegram tests.

These tests are designed to measure the reachability of the WhatsApp,

Facebook Messenger, and Telegram apps and web interfaces through DNS

lookups and by attempting to establish TCP connections to their

endpoints.

In light of increased censorship events over the last years, we decided

to monitor the accessibility of censorship circumvention tools as well.

Many circumvention tool sites were included in the Citizen Lab’s

global test list,

which we measured via OONI’s Web Connectivity test. But we

also ran OONI’s Vanilla Tor and Tor Bridge Reachability

tests, which are designed to measure the blocking of the Tor network and Tor bridges.

Once network measurement data was collected from all of these tests,

OONI data was subsequently

processed and

analyzed based on a standardized set of heuristics for detecting

internet censorship and traffic manipulation. We analyzed all OONI Probe

network measurements collected from Venezuela between 20th February 2014

to 10th August 2018.

The main findings though that we present in this study are based on:

Networks from which most of the recent measurements were collected from, namely: Digitel (AS264731), CANTV (AS8048), Movistar (AS6306) and Movilnet (AS27889).

Recent censorship findings that are currently more relevant.

Censorship findings that have been persistent over time (i.e. sites that remained blocked over time and which presented the highest ratio of anomalies).

Acknowledgement of limitations

The first limitation of this study is associated with the testing

period. This study includes an analysis of thousands of network measurements collected from Venezuela over the last four

years, between 20th February 2014 to 10th August 2018. Censorship events

that may have occurred before and/or after the analysis period are not

examined as part of this study.

Another limitation to this study is associated to the amount and types

of URLs that were tested for censorship. OONI’s Web Connectivity test was run to

measure the accessibility of 287 URLs

that are more relevant to the Venezuelan context and 1,123 internationally relevant sites.

All of these URLs were selected in collaboration with community members

over the last years. We acknowledge the URL selection bias and that the

testing sample of URLs might exclude many other sites that are blocked

in Venezuela. We therefore encourage researchers and community members

to continue reviewing and contributing to these test lists

to help improve future research and analysis.

Since block pages weren’t detected in Venezuela (at least for none of

the tested URLs), we present censorship findings with caution,

acknowledging that false positives may be present. This is the primary

reason why we mainly present findings that (a) presented consistent

anomalies over time (suggesting blocking) and (b) IPYS Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente were able to verify locally in

terms of (in)accessibility.

Finally, while network measurements were collected from multiple ASNs in

Venezuela, OONI’s software tests were not run

consistently across all networks. To share more recent and relevant

findings, we mainly focus on ASNs from which measurements were collected

the most over the last months: Digitel (AS264731), CANTV (AS8048),

Movistar (AS6306) and Movilnet (AS27889).

Findings

Recent OONI measurements

show the DNS blocking of local news outlets, sites expressing political

criticism, zello.com and currency exchange websites by (at least) four

Venezuelan ISPs. We also confirm the blocking of the Tor network

by state-owned CANTV.

Blocked websites

Following Venezuela’s 2015 elections, civil society groups IPYS

Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente

reported

(through the use of OONI Probe) on the blocking of a

number of websites, including currency exchange websites, blogs

expressing political criticism and media-related sites.

Our latest OONI findings show that such websites are currently blocked

by multiple Venezuelan ISPs and have remained blocked all along.

Measurements collected from Venezuela also suggest that a number of

other sites (such as el-nacional.com, lapatilla.com, elpitazo.com and

armando.info) have more recently been blocked as well.

As part of the following sections, we share OONI data pertaining to the

blocking of news outlets, sites expressing political criticism, currency

exchange sites and zello.com. The data we share is based on recent

measurements collected from four Venezuelan networks: Digitel

(AS264731), CANTV (AS8048), Movistar (AS6306) and Movilnet (AS27889).

Independent media websites are blocked in Venezuela (primarily by means

of DNS tampering), as illustrated in the following table (based on

recent OONI measurements).

El Pitazo is an independent news outlet run by Venezuelans that

started off as a YouTube

channel in 2014, expanded to a radio program, and eventually created a

media website. They aim to

share information with the most economically disadvantaged populations

of Venezuela and to shed light on issues that are otherwise censored by

state-owned media. El Pitazo is one of the few media outlets that has a

presence in all states in Venezuela, and whose news agenda is focused on

issues of community complaints, conflicts, and acts of corruption that

affect citizens and are of public interest.

A few months ago (in April 2018), Venezuela Inteligente and IPYS

Venezuela reported that two of El Pitazo’s domains

(elpitazo.com and elpitazo.info) were blocked by CANTV, Digitel,

Movistar, Movilnet and Intercable by means of DNS. Recent OONI data not

only shows that these domains remain blocked across ISPs, but that a

third domain of El Pitazo (elpitazo.ml) has been blocked as well.

Our findings pertaining to the recent testing of El Pitazo domains (over

the last two months) are aggregated in the following table (where

numbers represent the amount of measurements presenting each anomaly per

ISP).

| elpitazo.ml | elpitazo.info | elpitazo.com |

|---|

| CANTV (AS8048) | | | |

| DNS blocking | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| HTTP failures | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Digitel (AS264731) | | | |

| DNS blocking | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| HTTP failures | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Movilnet (AS27889) | | | |

| DNS blocking | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| HTTP failures | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Movistar (AS6306) | | | |

| DNS blocking | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| HTTP failures | 4 | 4 | 4 |

CANTV, Digitel and Movistar primarily appeared to block El Pitazo

domains by means of DNS, while most measurements collected from Movilnet

presented HTTP failures, suggesting potential HTTP blocking (though the

previous table links to some of the latest measurements presenting DNS

lookup errors).

The presence of both DNS lookup errors and HTTP failures may suggest

that ISPs employ both DNS and HTTP blocking techniques, or that HTTP

failures are caused as a result of DNS blocking techniques not being

implemented properly. Alternatively, they could be caused by a congested

network, server-side blocking, or if the site in question went down

during testing due to a DDoS attack. But we consider these possibilities

rather unlikely, as El Pitazo domains run behind Cloudflare, so they

should be quite resistant to failures.

Two months after El Pitazo domains were blocked, IPYS Venezuela

reported

that independent news outlets La Patilla and El Nacional were blocked as

well.

La Patilla was founded in 2010 by the

former CEO of Globovision (private Venezuelan TV channel) and is

ranked as one of the

most visited websites in Venezuela (ahead of other major news websites).

Currently, lapatilla.com is

accessible,

but was temporarily blocked

between 6th to 10th June 2018. OONI data collected on 6th June 2018

shows that the site was

accessible

on Movistar (AS6306), but

blocked

by state-owned CANTV (AS8048). Lapatilla.com was tested multiple times

on CANTV and all measurements presented the same HTTP failures and

“generic timeout errors”, suggesting HTTP blocking. CANTV though appears

to have

unblocked

the site by 11th June 2018, as corroborated by all subsequent

measurements.

El Nacional is Venezuela’s largest independent newspaper. Having run stories

on corruption, official brutality, electoral fraud, protests and other

stories critical of the government, the newspaper has received

significant government pressure over the last months. Similarly to La

Patilla, el-nacional.com primarily appears to be censored by means of

HTTP blocking, as suggested by HTTP failures (and “generic timeout

errors”) presented in recent OONI measurements. OONI data suggests that

the site’s blocked by CANTV

and

Movilnet,

but accessible on Digitel

and

Movistar.

HTTP failures indicative of blocking have been inconsistent or even

intermittent at times. This may suggest that internet censorship is not

implemented in a centralized way (i.e. by the same people) or in a way

that doesn’t affect all traffic.

A few days ago, Venezuela Inteligente

and IPYS Venezuela

reported that investigative journalism site armando.info was

inaccessible as well. This site is known for its critical and extensive

reporting on corruption and has been tested fairly regularly across ISPs

over the last two years. Most OONI measurements collected up until 12th

August 2018 suggested that the site was

accessible.

But on 13th August 2018, OONI Probe testing revealed that the site was

suddenly

inaccessible

on CANTV, presenting HTTP failures.

To investigate further, IPYS Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente

coordinated a measurement campaign, engaging locals across Venezuela to

test armando.info with OONI Probe

in various networks and regions of the country. In the evening of 13th

August 2018, armando.info was tested on CANTV, Movistar, CIX and Inter

in the following regions: Caracas, Carabobo, Táchira, Aragua, Bolívar,

Lara, Portuguesa and Monagas.

The table below summarizes the results of their testing.

What’s clear from recent OONI Probe measurements

(collected on 13th August 2018) is that the potential blocking of

armando.info is certainly inconsistent. We can see from the above table,

for example, that measurements collected from CANTV alternated between

being accessible and presenting HTTP failures. And these failures

weren’t triggered consistently over time and across regions.

The first CANTV measurements (presenting HTTP failures) in the early

evening of 13th August 2018 were collected from Caracas, while the last

CANTV measurements presented in the table (showing accessibility) were

collected from Táchira. The other

accessible

CANTV measurement at 6:16 pm was collected from Carabobo. This is

particularly interesting, as it may suggest that CANTV doesn’t roll out

the same censorship across its network, or that network or configuration

issues impacted the accessibility of armando.info.

Venezuela Inteligente and IPYS Venezuela (who are based in Caracas)

report that their experience in attempting to access armando.info (on

CANTV, Movistar and Digitel) is also inconsistent. As of 13th August

2018, there are moments when they can access the site and there are

moments when they can’t. While the armando.info site was

inaccessible,

as documented by OONI Web Connectivity tests, the server was reachable

and accepted TCP connections even as the HTTP exchange failed.

It therefore remains unclear whether armando.info is (or was)

intentionally blocked. However, it’s worth highlighting that

armando.info uses Google Shield, so we believe that server-side issues

are unlikely a reason for the observed network anomalies. Further

monitoring and

testing

is required.

Political criticism

Back in 2016, IPYS Venezuela and Venezuela Inteligente

reported

that a number of blogs critical of the government were blocked. Our

recent testing shows that the following two sites are currently blocked

across ISPs, primarily by means of DNS tampering.

The first site listed in the table above (vdebate.blogpost.com) is the

blog of an organization whose mission

is to “work for the recovery of democracy in Venezuela”. In

collaboration with other organizations and volunteers, they defend the

human, political and civil rights of Venezuelans. The second site listed

above (ovario2.com) is a blog that covers Venezuelan issues,

expressing political criticism.

Previous measurements collected from CANTV show that

alekboyd.blogspot.co.uk (a blog covering corruption and other political

issues) was

blocked

by CANTV by means of DNS tampering, up until (at least) 5th April 2018.

The blog though has since been unblocked and is currently

accessible.

Zello

Zello is a mobile app that serves as a

walkie-talkie over cell phone networks. Over the last years, it has been

popular among protesters

in Venezuela, Ukraine and

Russia.

During Venezuela’s 2014 protests, the app was reportedly blocked

for enabling “terrorist acts”.

Our recent testing suggests that the service remains blocked by (at

least) three ISPs, as illustrated below.

Currency exchange

Venezuela is experiencing the worst economic crisis

in its history. The country heavily depends on its oil (it has the

largest oil reserves in the world), the revenue of which supported its

social programmes and food subsidies. But when the price of oil fell,

these programmes became unsustainable and the country plummeted into a

food crisis.

Venezuela has established different exchange rate systems for its

national currency (the bolivar), with government control on the price of

basic goods, which is very high. In light of hyperinflation, coupled

with the devaluation of the bolivar in the black market, many

Venezuelans are opting for dollars rather than bolivares. But according

to the Venezuelan government, this

deepens

the country’s economic crisis.

To limit currency exchange, the Venezuelan government restricted access

to dollars and banned currency exchange websites in 2013,

more than 100 of which have reportedly been blocked.

Our recent testing (based on a limited amount of tested URLs)

reveals the blocking of the following currency exchange sites.

Miami-based DolarToday is run by the Venezuelan diaspora and is widely

used to track the plummeting black market value of the bolivar. It was

first reportedly blocked

in 2013. In late 2015, Venezuela’s central bank filed suit

in the US against dolartoday.com, alleging that the site’s managers

“committed cyberterrorism” and “sowed economic chaos” in Venezuela.

According to recent OONI measurements, dollartoday.com remains blocked

on CANTV.

Blocking of Tor

About Tor

The Tor network offers online

anonymity, privacy, and censorship circumvention. By bouncing

communications across a distributed network of relays, Tor hides its

users’ IP addresses. In doing so, Tor users not only have online

anonymity, but they can also bypass the blocking of sites and services

(since they access them from IP addresses allocated to different

countries).

As a result, the Tor network has become a target of censorship in

several countries around the world (such as

Egypt

and

Iran),

where governments attempt to make circumvention harder and improve their

online surveillance capabilities. To bypass Tor censorship, Tor bridges have been built to enable

users to connect to the Tor network in censored environments. Tor

Browser offers built-in (public) bridges that users can enable. If such

bridges are blocked, users can

request for (private) custom

bridges.

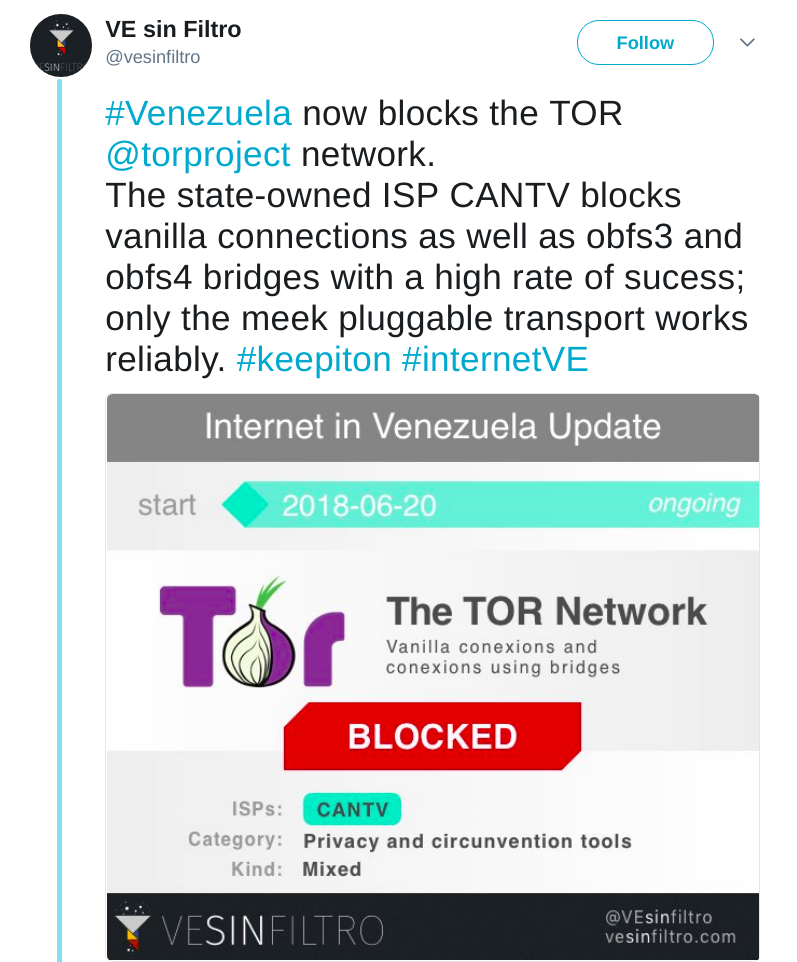

According to our recent testing and analysis, Venezuela now also

blocks

access to the major part of the Tor network and to many public obfs3 and

obfs4 Tor bridges. State-owned CANTV (AS8048) appears to have started

blocking the anonymity network around 20th June 2018, following months

of increased censorship, particularly targeting media websites.

Testing

OONI’s Vanilla Tor test is designed to

measure the reachability of the Tor network from the local vantage point of

the user. If the test does not manage to bootstrap a connection within

300 seconds, access to the Tor network is likely blocked. Similarly,

OONI’s Bridge Reachability test

measures the reachability of (public) Tor bridges by attempting to successfully

bootstrap a connection to them. To confirm the potential blocking with

more confidence (and rule out false positives), it’s useful to examine

measurements collected from the same network over time.

All measurements collected up until 6th June 2018 were successful,

showing that the Tor network was

accessible

in Venezuela. On 20th June 2018, however, Tor testing started to

fail

and civil society group Venezuela Inteligente reported the blocking of the

Tor network and Tor bridges by CANTV.

Most other measurements collected from 20th June 2018 onwards (from the

same network on an almost daily basis) have failed as well, strongly

suggesting that state-owned CANTV (AS8048) has been

blocking

access to the Tor network over the last two months. According to our

recent mid-August scans from CANTV, around 75% of the Tor network

appears to be blocked.

The lack of measurements between 6th to 20th June 2018 prevents us from

determining the exact date when Tor first got blocked. It’s worth noting

though that the blocking probably started on 20th June 2018, since

that’s when local civil society group, Venezuela Inteligente (who’s been monitoring internet

censorship in Venezuela over the last years), first

reported

on it.

To investigate further, OONI ran tests from a Raspberry Pi connected to

CANTV (AS8048) and performed some experiments examining the blocking of

Tor relays. Based on the following, we were able to successfully confirm

that connections to 74% of well-known IP:Port entities of the Tor

network were blocked (data:

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9).

The blocking was implemented on the reverse path,

so it was hard for the client to distinguish it from server-side

blocking:

The client could perform a TCP traceroute to all of the hops except for the last one; the client therefore got ICMP TTL Exceeded responses all the way long, but did not receive SYN-ACK.

The server sees SYN and sends SYN-ACK.

If the server rejects SYN with ICMP Port Unreachable - instead of RST - then the client gets the packet and the Linux TCP stack returns the “connection refused” error.

The server can perform a reverse TCP traceroute back to the client’s IP without anomalies.

Anomalous packet loss is observed on “parasitic” reverse TCP traceroutes, when the traceroute is executed using 5-tuple of existing connection. The anomaly seems to be located within the GlobeNet network, a US-based company that provides one of the backbone internet links to Venezuela’s state-owned CANTV.

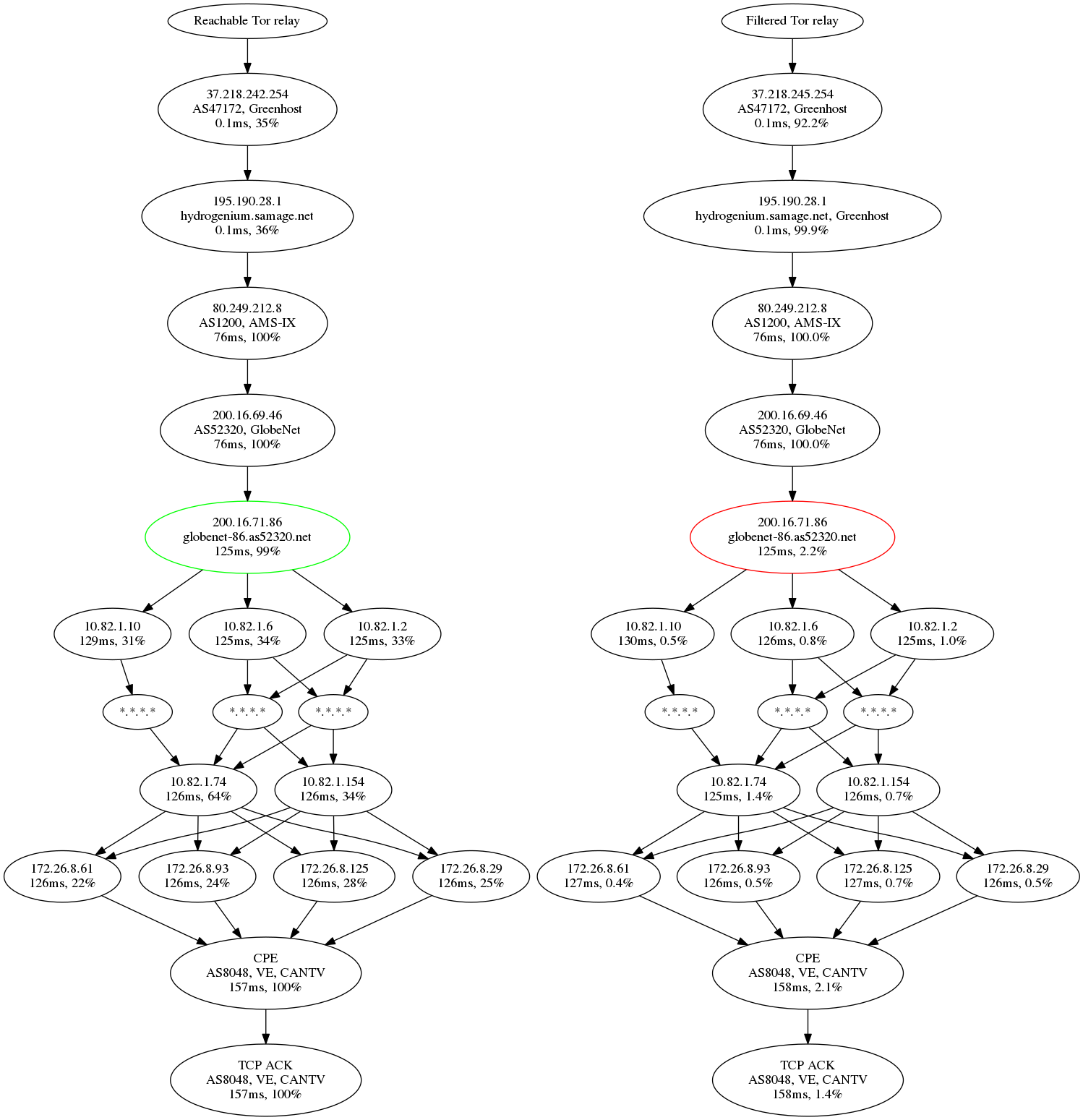

The “parasitic reverse traceroute” experiment was designed in the

following way: a) the client tried to establish 1000+ connections to the

TCP port of Tor relay, b) both “blocked”

and “non-blocked” relays were

tested, c) the relay was replying with a batch of marked SYN-ACKs with

varying TTL fields.

The following chart summarizes the percentage of

replies from specific routers and latency to them. It highlights that

the network anomaly occurs between two GlobeNet routers.

In addition to Tor blocking, Venezuela Inteligente also

reported

that access to a large amount of obfs3 and obfs4 bridges (i.e. Tor bridges enabling Tor censorship

circumvention) was blocked as well, making it practically impossible to

circumvent Tor blocking with built-in bridges. OONI’s bridge reachability

measurements corroborate these reports, showing the blocking of many Tor endpoints.

Bridge reachability tests run from CANTV (AS8048) in late June 2018 show

a failure rate of around 94% to known Tor bridges. Not all of these

failures are necessarily caused by blocking, as some bridges might be

offline or unreachable at any given moment. The high percentage of

connection failures though is highly indicative of blocking targeted to

well-known bridges. Repeated testing in mid-August 2018 showed a similar

percentage: 88% of running bridges were unreachable from a CANTV

vantage point.

The data from our scans is available via the following files: 1,

2, 3,

control.

Venezuela Inteligente tested a random sample of unlisted, publicly

available bridges from BridgeDB,

revealing that the failure rate is around 26% and that all testing to

private Tor bridges resulted in successful connections, regardless of

the type of bridge (including vanilla, obfs3 and obfs4 bridges). Forward

TCP traceroutes towards various accessible Tor relays go via GlobeNet,

Level3, Telia and Seabone. This also refutes the hypothesis that Tor

blocking depends on uplink (assuming that forward and reverse paths

match).

It’s worth highlighting that Tor’s website (torproject.org) has remained

accessible

in CANTV (and other networks),

even though access to the Tor network and obfs4 is blocked.

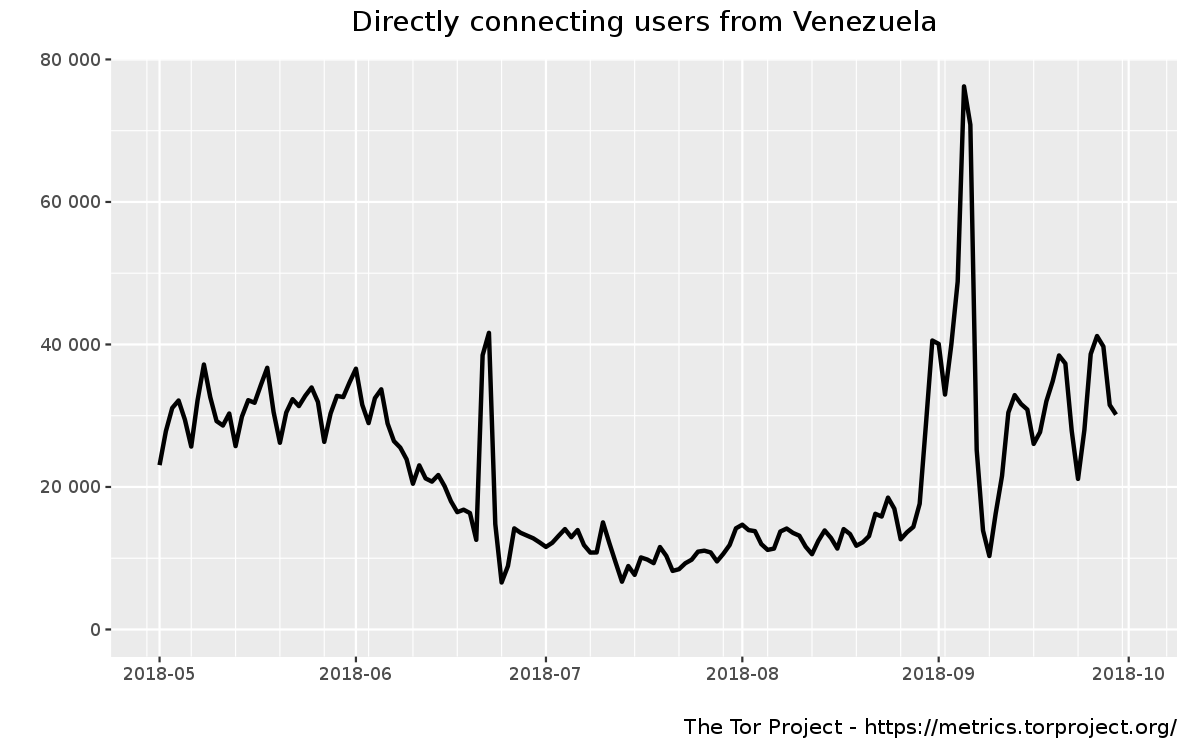

Tor unblocking

Further testing on 2nd October 2018 revealed that around 97% of public Tor nodes were reachable with TLS handshake from

the vantage point of CANTV. This corroborates local reports on Tor being accessible again.

While the precise date of unblocking is quite unclear, Tor Metrics suggest that Tor may have been unblocked on 30th August 2018, since we observe a spike in Tor usage, as illustrated below.

Conclusion

Censorship in Venezuela appears to be a symptom of its deep economic and

political crisis, which is considered the most severe crisis

in the country’s history. This is strongly suggested by the blocking of numerous currency exchange websites,

as well as by the blocking of independent news outlets

and

blogs

that discuss corruption and express political criticism.

The recent blocking of the Tor network

(which followed the blocking of news websites El Pitazo

and El Nacional)

may signify that internet censorship is becoming more dynamic in

Venezuela, as ISPs are taking extra steps to reinforce censorship and

make circumvention harder. The blocking of the Tor network - which offers online

anonymity, in addition to circumvention - might also suggest that the

government is attempting to improve its online surveillance

capabilities.

While Venezuelan ISPs primarily block sites by means of DNS tampering,

they also appear to be implementing HTTP filtering, suggesting a

variance in the filtering rules adopted by ISPs. And the variance, both

in terms of censorship techniques and censored platforms, across regions

and ISPs also indicates that internet censorship is not implemented in a

centralized way.

The censorship events identified as part of this study (particularly the

blocking of news websites and blogs) contradict the rights outlined by

the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in its

report

on Standards for a Free, Open and Inclusive Internet. Media censorship

and the blocking of blogs limit press freedom and the right to freedom

of thought and expression. In examining each right

outlined

by IACHR, questions around the necessity and proportionality of these

censorship events are inevitably raised, particularly in terms of how

they relate to human rights.

Venezuela’s political and economic environment is fragile and as events

unfold, its internet censorship apparatus may evolve. Continuing to

monitor censorship events in Venezuela is therefore essential. This

study can be reproduced and expanded upon through the use of OONI Probe and OONI data.