Zambia: Internet censorship during the 2016 general elections?

Maria Xynou (OONI), Arturo Filastò (OONI), Moses Karanja (CIPIT), Arthur Gwagwa (CIPIT), Isaac Rutenberg (CIPIT)

2016-10-11 10:52 UTC

A research study by the Open Observatory of Network Interference

(OONI) and Strathmore University’s Centre for Intellectual Property

and Information Technology Law (CIPIT).

Table of contents

Key Findings

Out of a total of 1,303 websites that were tested for censorship in

Zambia during and following its 2016 general election period, only 10 of

those sites

presented signs of

DNS, TCP/IP and HTTP interference, while previously

blocked

news outlets appeared to be accessible throughout the duration of the

testing period.

No block pages were detected as part of this study that could confirm

cases of censorship. Yet, the

findings illustrate

that connections to the websites of the World Economic Forum, the

Organization of American States (OAS), and an online-dating site

(pof.com) failed consistently from Zambia’s MTN network across the

testing period, while failure rates from control vantage points were

below 1%, indicating that these sites might have been blocked.

Pornography and sites supporting LGBT dating also appeared to be

inaccessible throughout the testing period, and such blocking can

potentially be legally justified under Zambia’s Penal

Code

and Electronic Communications and Transactions Act

2009.

However, it remains unclear why connections to other websites, such as

that of Pinterest, may have been tampered with during Zambia’s 2016

general elections.

The network tests run in Zambia

aimed at identifying “middle boxes” capable of performing internet censorship,

did not reveal the presence of censorship equipment.

However, this does not mean that censorship equipment is not present in the

country, but just that these particular tests were not able to highlight it’s

presence.

Introduction

Zambia is known

for its relative political stability, having avoided conflict and

maintained a multi-party democratic presidential system since 1991. As

part of its

Constitution,

Zambia guarantees press freedom and various human rights, including

freedom of expression and the right to access information, which are

enshrined in its Bill of

Rights.

Several cases of censorship however have been reported over the last

decades, including the

ban of The Post, one

of Zambia’s few independent newspapers, leading up to the country’s 1996

and 2016 general elections. Other cases of censorship were

reported

between 2013 and 2014, when four independent online news outlets -

Zambian Watchdog, Zambia

Reports, Barotse

Post, and Radio

Barotse - were blocked

for their critical coverage of the ruling party. OONI

revealed at the time that

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) filtering tactics were used to block

Zambian Watchdog’s website.

In light of Zambia’s 2016 general elections, the Open Observatory of

Network Interference (OONI), in

collaboration with Strathmore University’s Centre for Intellectual

Property and Information Technology Law

(CIPIT), conducted a study to examine whether

internet censorship events occurred during the election period. This

study was carried out through the collection of network measurements

from a local vantage point in Zambia, based on a set of OONI software

tests designed to examine

whether a set of websites were blocked, and whether systems that could

be responsible for internet censorship and surveillance were present in

the tested network (MTN Zambia).

The aim of this study is to increase transparency about potential

internet controls in Zambia which might have interfered with the

democratic process of elections. The following sections of this report

provide information about Zambia’s network landscape and internet

penetration levels, its legal environment with respect to freedom of

expression, access to information and privacy, as well as about cases of

censorship and surveillance that have previously been reported in the

country. The remainder of the report documents the methodology and key

findings of this study.

Background

Zambia is a landlocked country in Southern Africa, bordering with

Tanzania, Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola,

Malawi, Mozambique, Botswana and Namibia. Unlike most of its neighbors,

Zambia is known

for its political stability.

Following the country’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1964,

the United National Independence Party (UNIP) ruled Zambia for 18

years under a one-party

state with the motto “One Zambia, One

Nation”.

Deadly riots,

however, and an attempted

coup

appear to include some of the factors that led to Zambia’s transition to

a multi-party democracy and presidential system in 1991. Zambia has

since held a number of general elections within this new framework.

This, however, was almost disrupted by another failed coup attempt in

1997, resulting in the

death sentence of 103 soldiers. Zambia’s last general elections were

held on 11th August 2016 which

resulted in

a victory for the Patriotic Front (PF), whose candidate Edgar Lungu was

elected President for a five-year term.

Zambia was one of the world’s fastest growing

economies

over the last decade, but the falling copper prices, exports and foreign

direct investment have

weakened the

economy in recent years, while the rate of

inflation

has increased. Corruption also appears to remain

pervasive in the country

despite anti-corruption

efforts,

such as the strengthening of legal and institutional frameworks.

Multiple ethnic

minorities live in Zambia,

the Bembe people being the largest ethnic group. The majority of the

population is

Protestant,

while smaller

percentages

of the population are Roman Catholic, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu and Bahá’í.

Despite the presence of diverse ethnic and religious groups, civil war

has been prevented in the country. Xenophobic violence however has been

an issue, recently resulting in the death of

Rwandans who were

accused of engaging in ritual killings in Lusaka.

Food shortages and HIV/AIDS are some of the main issues that have

affected Zambia in recent decades. Around 70% of the population is

estimated to live on less

than US\$1 per day. A national disaster due to droughts was

declared in 2005,

when the President appealed for food aid. While Zambia consists of a

population of around 16

million,

more than 1

million

people are estimated to be living with HIV/AIDS.

Network landscape and internet penetration

Zambia was one of the first countries in Sub-Saharan Africa to adopt the

internet, when satellite and dial-up technology were installed at the

University of Zambia in the early 1990s. Today, three operators provide

Zambia’s national fiber backbone: Zambia Telecommunications Ltd

(Zamtel) and Zambia Electricity Supply

Corporation Ltd (ZESCO) - both of which are

state-owned - as well as Copperbelt Energy Corporation

(CEC), which is privately-owned.

All internet and mobile service providers in Zambia are privately-owned,

with the exception of Zamtel, which is state-owned. Overall, Zambia has

16 different Internet Service Providers (ISPs), and 3 mobile operators:

Airtel, MTN and Zamtel.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 Q1-2 |

|---|

| Population-CSO Estimate | 13,092,666 | 13,721,498 | 14,156,468 | 14,605,555 | 15,068,792 | 15,545,778 | 16,037,474 |

| Number of Mobile Operators | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of PSTN Operators | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of Active ISPs | - | - | - | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

Source: Zambia Information and Communications Technology Authority

Zamtel has the largest share of internet subscriptions, but the smallest

share in the mobile phone market, where Airtel and MTN have the

largest

shares.

| Network Coverage | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 Q1 |

|---|

| Internet Points of Presence (Districts) | - | - | - | 99 | - | - | - |

| PSTN Area Coverage (%) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| National Network Geographical Coverage | | | | | | | |

| Airtel Zambia | - | - | - | 42.7% | 42.7% | 42.7% | 42.7% |

| MTN Zambia | - | 36.6% | 37.5% | 39.4% | 31.7% | 45.4% | 43.5% |

| Zamtel | - | 75.0% | 75.0% | 29.7% | 27.0% | 27.0% | 27.0% |

Source: Zambia Information and Communications Technology Authority

Internet penetration in Zambia is currently limited to about

21%

of the population, according to the International Telecommunication

Union

(ITU),

the World

Factbook,

and Internet World

Stats. The limited

amount of internet users in Zambia is due to a number of reasons,

including high costs of hardware, software and access to the internet,

poor network coverage, erratic and expensive electricity, and high

levels of illiteracy and poverty

(60% of the

population is estimated to live below the poverty line, and

42% are

considered to live in extreme poverty). Nonetheless, access to

information and communication technologies (ICTs) has been increasing

steadily over the last few years, growing from a penetration rate of

10% in 2010 to about 21% in

2016.

The vast majority of Zambian ICT users access the internet via mobile

phones, as 70.5% of

the population is estimated to have mobile phone subscriptions, while

less than 1% of

Zambians access the internet from their homes via fixed line

subscriptions. As of 2013, SIM card

registration

with an original and valid identity card is required for mobile phone

subscriptions.

Zambia’s Information and Communications Technology Authority

(ZICTA) estimates that

35.6% of Zambia’s

mobile phone subscribers use the internet in 2016, as illustrated below:

| Indicator | Number | Penetration Rate |

|---|

| Mobile Subscription | 11,309,494 | 70.50% |

| Fixed Line Subscription | 115,423 | 0.72% |

| Mobile Internet Users | 5,715,493 | 35.60% |

| Fixed Internet Subscription | 35,960 | 0.22% |

Source: Zambia Information and Communications Technology Authority

Blackberry devices appear to be used the most

due to their cheap subscription fees, while the increasing number of

mobile internet users and government cybercafe

regulations

appear to be some of the reasons leading to the decreased popularity of

cybercafes in recent years.

Legal environment

Zambia’s ICT sector is regulated by ZICTA,

which was established under the 2009 Information and Communications

Technologies

Act.

As part of its mandate, ZICTA manages the registration for the .zm

country code top-level domains, according to provisions under the 2009

Electronic Communications and Transaction

Act. The Independent

Broadcasting Authority is also responsible for

regulating some internet content.

Freedom of expression

Freedom of expression is enshrined in the Bill of

Rights

which is included in Part III of Zambia’s Constitution. According to

Article 21 of the Bill of Rights:

(1) A person has the right to freedom of expression which includes –

(a) freedom to hold an opinion;

(b) freedom to receive or impart information or ideas;

© freedom of artistic creativity;

(d) academic freedom; and

(e) freedom of scientific and technological research, as prescribed.

Clause 2 of Article 21 of the Bill of Rights specifies the conditions

under which freedom of expression is restricted:

(2) Clause (1) does not extend to –

(a) conduct or statements which incite war, genocide, crimes against

humanity or other forms of violence; or

(b) statements which –

(i) vilify or disparage others; or

(ii) incite hatred.

While freedom of expression is guaranteed under Zambia’s Constitution,

in practice this right can be limited by broad interpretations of laws

that restrict expression in the interest of national security, public

order and safety.

Press freedom

Zambia’s Constitution was recently

amended

to include significant protections for press freedom.

Freedom of the media (electronic, broadcasting, print, and other forms)

is guaranteed under Article 23 of the Bill of

Rights,

though “the State may license broadcasting and electronic media where

it is necessary to regulate signals and signal distribution.”

Clause 2 of Article 23 explicitly prohibits the State from exercising

control or interfering with the production or circulation of

publications, or with the dissemination of information through any

media.

Furthermore, clause 4 of Article 23 guarantees the independence of the

public media to determine the editorial content of their broadcasts and

communications, as well as the right to present divergent views and

dissenting opinions.

In practice, however, press freedom can potentially be limited by

various statutes. Zambia’s Penal

Code,

for example, includes clauses that criminalize the defamation of the

president and allow the president to ban publications that are

considered to be “contrary to the public interest”.

Article 22 of the Bill of

Rights

guarantees the right to access information. Specifically, clause 1 of

Article 22 states that individuals have the right to access information

held by the State or another person which is lawfully required for the

exercise or protection of a right or freedom.

While the process of drafting Zambia’s Access to Information (ATI) Bill

started in 2002, the Bill has still not been enacted into law, thus

limiting the right to access information from being exercised in

practice.

Various non-profit organizations, including

IFEX and

the Open Society Initiative for Southern

Africa,

have criticised the delay and have encouraged the Zambian government to

create a timeline for enacting the Access to Information (ATI) Bill into

law.

Privacy

The right to privacy is enshrined in Article 19 of Zambia’s Bill of

Rights,

which extends to the protection of a person’s communications privacy

from infringement.

Data protection is included in Part VII (“Protection of Personal

Information”) of the 2009 Electronic Communications and Transactions

Act,

and Article 42 of the Act specifies the principles for the electronic

collection of personal information.

While most of these principles include important provisions for data

protection, it is noteworthy that principle 9 enables data controllers

to “use any personal information to compile profiles for statistical

purposes and may freely trade with such profiles and statistical data,

as long as the profiles or statistical data cannot be linked to any

specific data subject by a third party”. This principle raises concerns,

as research

has shown that “anonymized datasets” can be de-anonymized by third

parties.

Censorship and surveillance

Zambia’s Electronic Communications and Transactions Act

2009

(Part XI, “Interception of Communication”) includes details about how

lawful interception is carried out, generally requiring a court order

(Article 66).

Article 65 of the Act establishes the Central Monitoring and

Coordination Centre, which manages and aggregates all authorised

interceptions of communications, and which is operated by the department

responsible for Government communications. According to Article 77,

service providers are required to install hardware and software

facilities and devices that enable the “real-time” and “full-time”

interception of communications upon request by law enforcement agencies.

Service providers are also required to provide interfaces for

transmitting all intercepted communications directly to the Central

Monitoring and Coordination Centre.

Part XIV (“Cyber Inspectors”) of the Act details the appointment and

powers of cyber inspectors. According to Article 94, a cyber inspector

may “monitor and inspect any website or activity on an information

system in the public domain and report any unlawful activity to the

appropriate authority”.

Pornography is prohibited under Article 102 of Part XV (“Cyber crime”)

of the Act, according to which a fine and/or imprisonment can be imposed

on any person that “procures any pornography through a computer system

for oneself or for another person”, or “possesses any pornography in a

computer system or on a computer data storage medium”.

Previous cases of internet censorship and surveillance

Africa’s first known case of internet censorship occurred in Zambia

twenty years ago.

Leading up to the 1996 general elections, the government of Zambia

banned edition 401 of

The Post, one of Zambia’s three

primary newspapers, and ordered its removal from the newspaper’s

website. This incidence of censorship

reportedly occurred

because edition 401 stated that the government was secretly planning to

hold a referendum on the constitution without providing the public with

much prior notice.

In addition to censoring the online version and distribution of The

Post’s 401 edition, the government also

threatened

to hold the site’s Internet Service Provider (ISP), Zamnet, criminally

liable for the content, and three of the edition’s editors were

arrested under the

Official Secrets Act on charges for receiving and publishing “classified

information”.

No other incidents of internet censorship were reported in Zambia for

more than a decade.

The first new censorship attempt started in late 2012 when Zambia’s

registrar of societies

threatened

to deregister the Zambian

Watchdog, an investigative online

media that focuses on corruption and other major crimes, for allegedly

failing to pay required fees and submit a postal address. While this

attempt was unsuccessful, the news website was blocked during the

following year.

Four independent online news outlets - Zambian

Watchdog, Zambia

Reports, Barotse

Post, and Radio

Barotse - were

reportedly

censored

for about nine months, from July 2013 until April 2014, for their

critical coverage of the ruling party under President Sata.

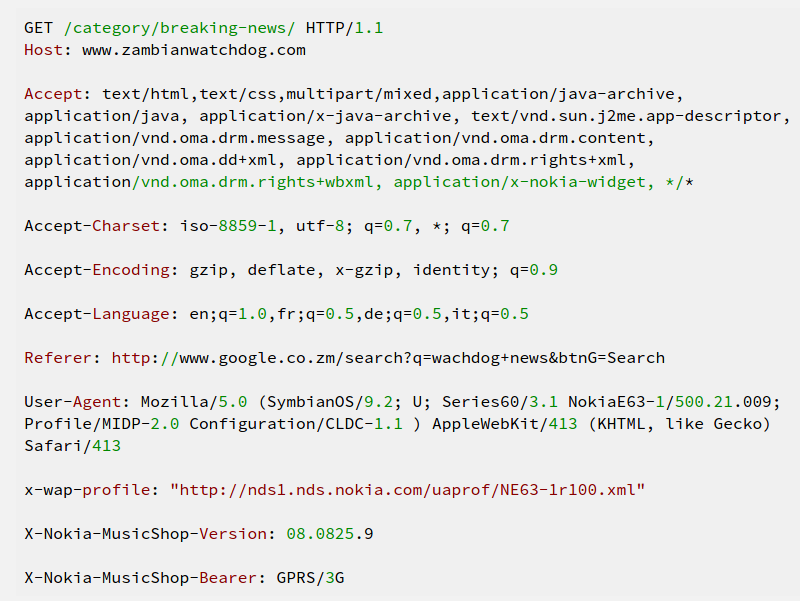

OONI revealed at the time

that Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) filtering tactics were used to block

Zambian Watchdog’s website. According to the collected data, “reset”

packets were being injected by DPI device to terminate connections to

www.zambiawatchdog.com, leading to

the site being inaccessible.

Source: Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), “Zambia, a

country under Deep Packet Inspection”

Initially, only unencrypted connections to Zambian Watchdog’s website

were found to be blocked, but further

testing

also revealed the blocking of encrypted SSL connections to the website.

The Zambian government did not officially claim any responsibility in

relation to this censorship, but Vice President Guy Scott reportedly

stated

that the Zambian Watchdog’s website deserved to be blocked because it

was “promoting hate speech” and its reporting was “malicious, vicious

and fictitious”.

During this period, several journalists suspected of working for the

Zambian Watchdog were

arrested

on charges that included the “possession of obscene material”. Two years

later, one of those journalists was acquitted after a court

ruled

that evidence used against him had been planted.

In an open

letter,

news outlet Zambia Reports claimed that access to its website was also

blocked completely, and that it had received no prior notification or

explanation from the government in regards to why its website was being

blocked. Zambia Reports also revealed that it had filed a complaint

regarding the blocking of their IP address to ZICTA.

Censorship in Zambia is

reportedly

enabled through collaboration with Chinese companies, such as

Huawei and ZTE,

that equip Zambian ISPs with DPI technology that can be used for the

purpose of blocking social media and “unfriendly” websites. The Zambian

government has

allegedly

spent about USD 1.8 million on its partnership with Chinese companies,

involving the installation of an internet monitoring facility and

possibly the development of backdoors within networks.

Zambian authorities might have also acquired sophisticated spyware,

known as Remote Control System

(RCS),

by an Italian surveillance company called Hacking

Team. According to one of Hacking Team’s

brochures,

RCS spyware can remotely monitor and log activity on computers and

smartphones, while being undetected by anti-virus, anti-spyware and

anti-keylogging software. After Hacking Team got

hacked

last year, leaked emails

revealed that the Zambian government intended to acquire spyware for

monitoring and intercepting communications. This, though, has not been

confirmed to date, and it remains unclear if the Zambian government is

indeed using such technologies.

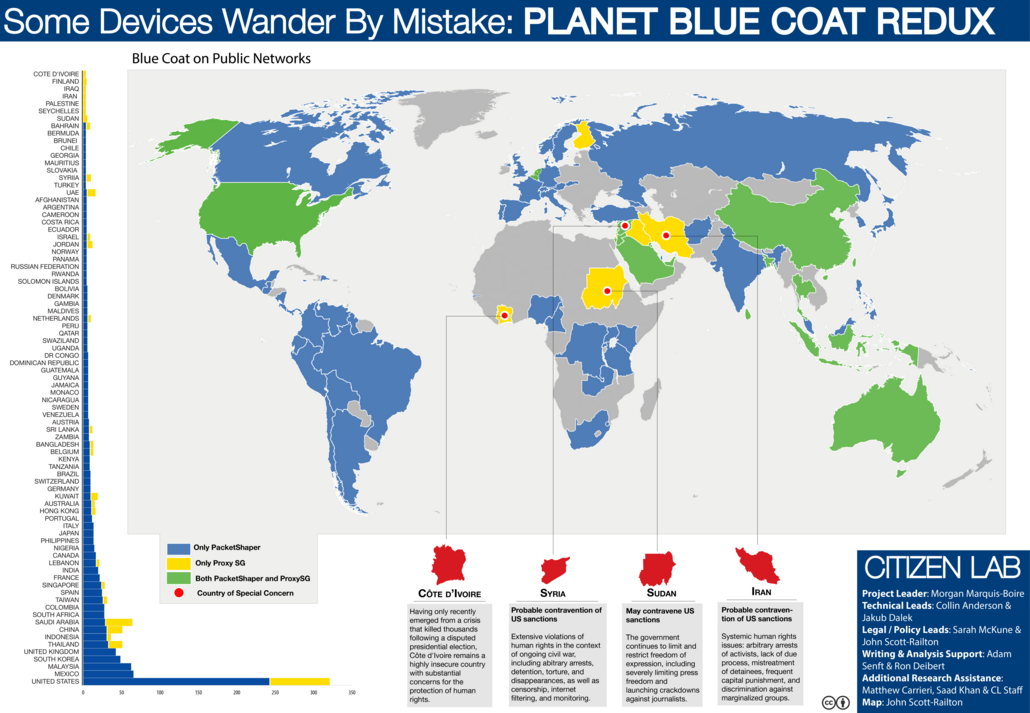

In 2013 Citizen Lab researchers

detected

the presence of a Blue Coat PacketShaper device in Zambia. Blue Coat

Inc. is a California-based company which is known for developing,

marketing, and exporting technologies that can be used to monitor

internet traffic, block websites, and track users’ online activities and

communications.

As part of its

study,

the Citizen Lab used a combination of network measurement and scanning

methods and tools to identify instances of Blue Coat ProxySG and

PacketShaper devices around the world. The research findings show the

presence of Blue Coat PacketShaper in Zambia, as illustrated below:

Source: Citizen Lab, “Some Devices Wander By Mistake: PLANET BLUE COAT

REDUX”

Numerous

reports

surfaced over the last years accusing the Zambian government of

extensive surveillance activities, some of which may have even

targeted cabinet

officials,

such as the foreign minister, and local leaders. Similarly, members of

the opposition have

accused

the Zambian government of eavesdropping on their phone conversations.

Last year, two journalists

petitioned

the High Court of Zambia to inquire into allegations of phone tapping by

Airtel - Zambia’s largest mobile service provider - under the previous

government.

Zambia’s 2016 general elections and constitutional referendum

Zambia has a reputation for political

stability, especially

in comparison to its neighbours, being governed by a unitary presidential

republic.

The 2011 elections

resulted in a

victory for the Patriotic Front (PF), whose candidate Michael Sata was

elected President for a five-year term. However, following the death of

President Sata in October 2014, early presidential

elections

were held last year to elect a successor to complete the remainder of

his term. This resulted in the election of PF candidate Edgar Lungu, who

beat Hakainde Hichilema of the United Party for National Development

(UPND) by a very narrow margin. The UPND did not

accept

the credibility of the 2015 election.

On 11th August 2016, Zambia held its general

elections to

elect the President and National Assembly. Leading up to the elections,

violent outbreaks occurred in Lusaka after the government

banned

The Post, one of Zambia’s few independent newspapers, on 10th June.

Due to the violence, the Electoral Commission suspended campaigning

activities in Lusaka and Namwala for ten days. During this period, the

government also took

action

against The Post on the ground of unpaid taxes of around USD 6

million. The ban on the newspaper was eventually

lifted

more than a month later.

This is not the first time that The Post was banned. This

previously occurred in

1996, leading up to the country’s general elections.

Members of the UPND, Zambia’s main opposition party, were

arrested

a few weeks before the 2016 general elections on the grounds that they

were trying to start a private militia. The police started off by

raiding the UPND Head

Office

and questioning staff members and volunteers of the party. According to

the UPND, this was part of the PF government’s persecution and abuse

towards them. The police subsequently raided the house of the UPND’s

Vice

President,

and a total of 28 people were arrested as part of the raid.

Further

controversy

emerged in the printing of the ballot papers, which had previously been

printed in South Africa. This time, the Electoral Commission of Zambia

awarded the contract to Al Ghurair Printing &

Publishing, a Dubai-based firm,

which prepared the ballot papers used for Zambia’s 2016 elections.

Opposition members and civil society groups

criticised

this move on the grounds that the contract with the Dubai firm was

significantly more expensive than previous contracts, and that it

increased the possibility of electoral fraud. Similar concerns were also

raised in regards to the transport and distribution of the ballot

papers.

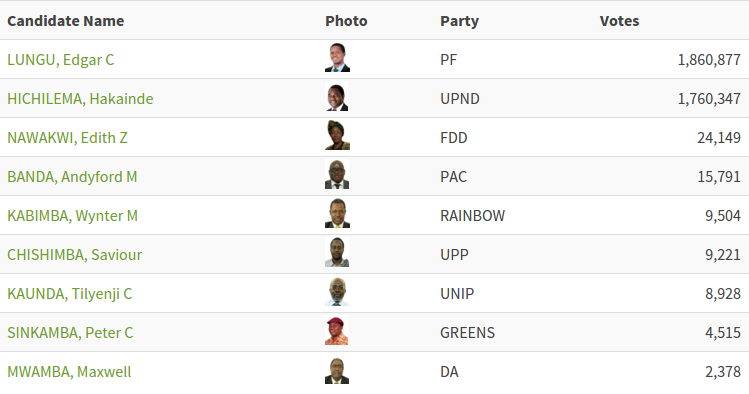

The 2016 elections presented a “large turnout” and were

characterized

as “calm and peaceful”, while including a tight competition between the

PF and the UPND. A total of nine candidates registered to run for the

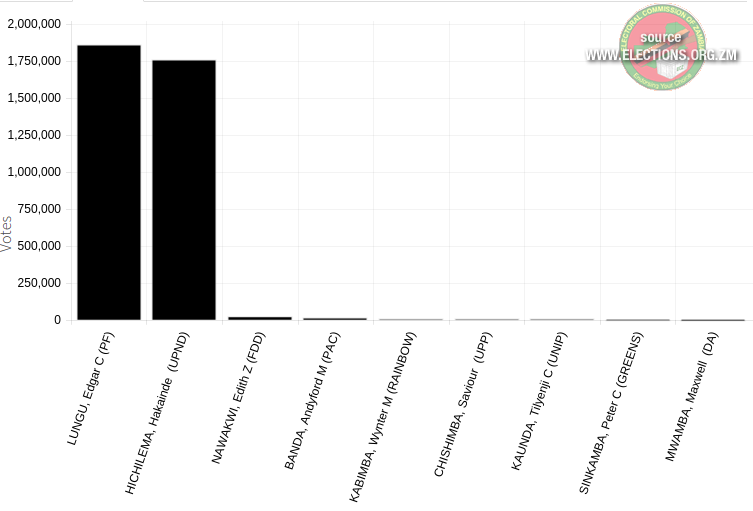

presidency, as illustrated below:

Source: Electoral Commission of Zambia, General Election of 2016

Edgar Lungu of the PF won the 2016 elections and was re-elected for a

five-year term, beating the UPND again with a very close margin. The

chart below illustrates that the PF and UPND acquired the vast majority

of votes within Zambia:

Source: Electoral Commission of Zambia, General Election 2016

While the PF and UPND each acquired a similar share of the total votes

in the presidential elections, the PF

won

a majority in the National Assembly, winning 80 of the 156 elected

seats. In spite of the pre-election violence, the 2016 elections were

generally

characterized

as “peaceful”. However, election observers in Zambia

reported

that the media biased the vote in favour of the ruling party.

Following the elections, the UPND

accused

the Electoral Commission of Zambia for participating in fraud due to its

significant delay in announcing the results and

stated

that the vote was rigged. The US-based Carter Center also expressed

concern

in regards to the delay of the announcement of the results, and stated

that the elections were characterized by significant inter-party

tensions and polarization.

Protests sprung against the reelection of President Lungu, resulting in

the arrest of 133

protesters.

About a week after the elections, subscribers on MTN Zambia, Airtel

Zambia, and Vodafone’s 4G service expressed

complaints

regarding an internet shutdown, some attributing this to state sponsored

censorship in an attempt to stifle opposing views towards the election

outcomes. MTN and Airtel acknowledged the disruptions, but it remains

unclear

if the outage was ordered by the government or not.

Alongside the elections, a constitutional

referendum was

also held in Zambia on 11th August 2016. Voters were asked to answer the

following question:

“Do you agree to the amendment to the Constitution to enhance the Bill

of rights contained in Part III of the Constitution of Zambia and to

repeal and replace Article 79 of the Constitution of Zambia?”

The referendum sought to enhance and amend Zambia’s Bill of

Rights

- a declaration of individual rights and freedoms, as issued by the

national government - by repealing and replacing Article 79, which

dictates the process of future amendments. Specifically, the

changes to the

Bill of Rights would include amendments to the “Civil and Political

Rights” section, and the addition of the “Economic, Social, Cultural and

Environmental Rights” and “Further and Special Rights” sections. For the

referendum to pass, a majority ‘yes’ vote was required, along with a

turnout of at least 50% eligible voters.

The referendum was criticised in advance by media organizations, who

questioned whether

the majority of Zambia’s voters understand the Bill of Rights and what

they were asked to answer through the referendum. The PF government was

also

criticised

for its delay in releasing the Bill of Rights, preventing voters from

reading in advance the contents that they were asked to vote for or

against. This was

characterized

as a ploy to deprive the people of Zambia from the opportunity to make

informed decisions in regards to the country’s constitution. Similarly,

the decision to combine the 2016 general election with a referendum was

characterized

as an undemocratic ploy by the PF government to acquire votes.

While the majority vote (71%) of Zambia’s 2016 constitutional referendum

was in favour, the turnout was below the 50%

threshold,

preventing the validation of the result.

Examining internet censorship during Zambia’s 2016 general elections

The Open Observatory of Network Interference

(OONI), in collaboration with Strathmore

University’s Centre for Intellectual Property and Information

Technology Law (CIPIT), performed a study of

internet censorship in Zambia during its 2016 general elections.

The aim of this study was to understand whether and to what extent

censorship events occurred during the election period, limiting voters’

rights to access and disseminate information.

The sections below document the methodology and key findings of this

study.

Methodology

The methodology of this study, in an attempt to identify potential

censorship events in Zambia during its 2016 election period, included

the following:

A list of

URLs

that are relevant and commonly accessed in Zambia was created, and such

URLs - along with other

URLs

that are commonly accessed around the world - were tested for blocking

based on OONI’s free software tests. Such tests were run from a local

vantage point (the ISP MTN) in Zambia (AS 36962), and they also examined whether

systems that are responsible for censorship, surveillance and traffic

manipulation were present in the tested network. Once network

measurement data was collected from these tests, the data was

subsequently processed and analyzed based on a set of heuristics for

detecting internet censorship and traffic manipulation.

The testing period started on 11th August 2016 - the day of Zambia’s

general elections - and concluded on 24th August 2016. During this

period, network measurements were collected every day through the use of

OONI’s software distribution for Raspberry

Pis.

Creation of a Zambian test list

An important part of identifying censorship is determining which

websites to examine for blocking.

OONI’s software (called

OONI Probe) is designed to examine URLs contained in specific lists

(“test lists”) for censorship. By default, OONI Probe examines the

“global test

list”,

which includes a wide range of internationally relevant websites, most

of which are in English. These websites fall under 30

categories,

ranging from news media, file sharing and culture, to provocative or

objectionable categories, like pornography, political criticism, and

hate speech.

These categories help ensure that a wide range of different types of

websites are tested, and they enable the examination of the impact of

censorship events (for example, if the majority of the websites found to

be blocked in a country fall under the “human rights” category, that may

have a bigger impact than other types of websites being blocked

elsewhere). The main reason why objectionable categories (such as

“pornography” and “hate speech”) are included for testing is because

they are more likely to be blocked due to their nature, enabling the

development of heuristics for detecting censorship elsewhere within a

country.

In addition to testing the URLs included in the global test list,

OONI Probe is also designed to examine a test list which is specifically

created for the country that the user is running OONI Probe from, if such

a list exists. Unlike the global test list, country-specific test

lists

include websites that are relevant and commonly accessed within specific

countries, and such websites are often in local languages. Similarly to

the global test list, country-specific test lists include websites that

fall under the same set of 30

categories,

as explained previously.

All test lists are hosted by the Citizen

Lab on

GitHub, supporting OONI

and other network measurement projects in the creation and maintenance

of lists of URLs to test for censorship. Some criteria for adding URLs

to test lists include the following:

The URLs cover topics of socio-political interest within the country

The URLs are likely to be blocked because they include sensitive

content (i.e. they touch upon sensitive issues or express

political criticism)

The URLs have been blocked in the past

Users have faced difficulty connecting to those URLs

The above criteria indicate that such URLs are more likely to be

blocked, enabling the development of heuristics for detecting censorship

within a country. Furthermore, other criteria for adding URLs are

reflected in the 30

categories

that URLs can fall under. Such categories, for example, can include

file-sharing, human rights, and news media, under which the websites of

file-sharing projects, human rights NGOs and media organizations can be

added.

As part of the study on whether censorship events occurred during the

2016 election period in Zambia, OONI and CIPIT created a

country-specific test list for

Zambia,

containing URLs to be tested for blocking. The added URLs are specific

to the Zambian context, and include a number of websites that express

political criticism towards the PF party and report on human rights

violations. Overall, 90 different

websites,

mostly grouped under the “political criticism” and “human rights”

categories, are included in the Zambian test list, and were tested for

censorship.

A core limitation to the study is the bias in terms of the URLs that

were selected for testing. As the testing period covered Zambia’s 2016

general elections, the URL selection criteria included the following:

Websites that were more likely to be blocked, because their content

expressed political criticism towards the ruling PF party.

Websites of organizations that were known to have previously been

blocked (such as zambiawatchdog.com) and were thus likely to be

blocked again.

Websites reporting on human rights restrictions and violations,

reflecting criticism towards the ruling PF party.

The above criteria reflect bias in terms of which URLs were selected for

testing, as one of the core aims of this study was to examine whether

and to what extent websites reflecting criticism towards the ruling

party were blocked during the election period, limiting open dialogue

and access to information across the country. As a result of this bias,

it is important to acknowledge that the findings of this study are only

limited to the websites that were tested, and do not provide a complete

view of other censorship events that may have taken place during the

2016 election period.

OONI network measurements

The Open Observatory of Network Interference

(OONI) is a free software project that

aims to increase transparency about internet censorship and traffic

manipulation around the world. Since 2011, OONI has developed multiple

free and open source software

tests designed to

examine the following:

Blocking of websites.

Detection of systems responsible for censorship and

traffic manipulation.

Reachability of circumvention tools (such as Tor, Psiphon,

and Lantern) and sensitive domains.

As part of this study, OONI’s distribution for embedded

devices (called

Lepidopter) was run from a local vantage point in Zambia, including

the following software tests:

The web connectivity test was run with the aim of examining whether a

set of URLs (included in both the “global test

list”,

and the recently updated “Zambian test

list”)

were blocked during the testing period and if so, how.

As the presence of Blue Coat filtering technology had previously been

detected

by the Citizen Lab in Zambia (see section on “Cases of internet

censorship and surveillance”), the HTTP invalid request

line

and HTTP header field

manipulation

tests were run for the purpose of examining whether such systems were

present in the tested network during the testing period.

The sections below document how each of these tests are designed for the

purpose of detecting cases of internet censorship and traffic

manipulation.

Web connectivity

This test

examines

whether websites are reachable and if they are not, it attempts to

determine whether access to them is blocked through DNS tampering, TCP

connection RST/IP blocking or by a transparent HTTP proxy. Specifically,

this test is designed to perform the following:

Resolver identification

DNS lookup

TCP connect

HTTP GET request

By default, this test performs the above (excluding the first step,

which is performed only over the network of the user) both over a

control server and over the network of the user. If the results from

both networks match, then there is no clear sign of network

interference; but if the results are different, the websites that the

user is testing are likely censored.

Further information is provided below, explaining how each step

performed under the web connectivity test works.

1. Resolver identification

The domain name system (DNS) is what is responsible for transforming a

host name (e.g. torproject.org) into an IP address (e.g. 38.229.72.16).

Internet Service Providers (ISPs), amongst others, run DNS resolvers

which map IP addresses to hostnames. In some circumstances though, ISPs

map the requested host names to the wrong IP addresses, which is a form

of tampering.

As a first step, the web connectivity test attempts to identify which

DNS resolver is being used by the user. It does so by performing a DNS

query to special domains (such as whoami.akamai.com) which will disclose

the IP address of the resolver.

2. DNS lookup

Once the web connectivity

test

has identified the DNS resolver of the user, it then attempts to

identify which addresses are mapped to the tested host names by the

resolver. It does so by performing a DNS lookup, which asks the resolver

to disclose which IP addresses are mapped to the tested host names, as

well as which other host names are linked to the tested host names under

DNS queries.

3. TCP connect

The web connectivity test will then try to connect to the tested

websites by attempting to establish a TCP session on port 80 (or port

443 for URLs that begin with HTTPS) for the list of IP addresses that

were identified in the previous step (DNS lookup).

4. HTTP GET request

As the web connectivity

test

connects to tested websites (through the previous step), it sends

requests through the HTTP protocol to the servers which are hosting

those websites. A server normally responds to an HTTP GET request with

the content of the webpage that is requested.

Comparison of results: Identifying censorship

Once the above steps of the web connectivity test are performed both

over a control server and over the network of the user, the collected

results are then compared with the aim of identifying whether and how

tested websites are tampered with. If the compared results do not

match, then there is a sign of network interference.

Below are the conditions under which the following types of blocking are

identified:

DNS blocking: If the DNS responses (such as the IP addresses

mapped to host names) do not match.

TCP/IP blocking: If a TCP session to connect to websites was

not established over the network of the user.

HTTP blocking: If the HTTP request over the user’s network

failed, or the HTTP status codes don’t match, or all of the

following apply:

The body length of compared websites (over the control server

and the network of the user) differs by some percentage

The HTTP headers names do not match

The HTML title tags do not match

It’s important to note, however, that DNS resolvers, such as Google or a

local ISP, often provide users with IP addresses that are closest to

them geographically. Often this is not done with the intent of network

tampering, but merely for the purpose of providing users with localized

content or faster access to websites. As a result, some false positives

might arise in OONI measurements. Other false positives might occur when

tested websites serve different content depending on the country that

the user is connecting from, or in the cases when websites return

failures even though they are not tampered with.

HTTP invalid request line

This

test

tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”) which

could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

Instead of sending a normal HTTP request, this test sends an invalid

HTTP request line - containing an invalid HTTP version number, an

invalid field count and a huge request method – to an echo service

listening on the standard HTTP port. An echo service is a very useful

debugging and measurement tool, which simply sends back to the

originating source any data it receives. If a middle box is not present

in the network between the user and an echo service, then the echo

service will send the invalid HTTP request line back to the user,

exactly as it received it. In such cases, there is no visible traffic

manipulation in the tested network.

If, however, a middle box is present in the tested network, the invalid

HTTP request line will be intercepted by the middle box and this may

trigger an error and that will subsequently be sent back to OONI’s

server. Such errors indicate that software for traffic manipulation is

likely placed in the tested network, though it’s not always clear what

that software is. In some cases though, censorship and/or surveillance

vendors can be identified through the error messages in the received

HTTP response. Based on this technique, OONI has previously

detected the use

of BlueCoat, Squid and Privoxy proxy technologies in networks across

multiple countries around the world.

It’s important though to note that a false negative could potentially

occur in the hypothetical instance that ISPs are using highly

sophisticated censorship and/or surveillance software that is

specifically designed to not trigger errors when receiving invalid HTTP

request lines like the ones of this test. Furthermore, the presence of a

middle box is not necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as

they are often used in networks for caching purposes.

This

test

also tries to detect the presence of network components (“middle box”)

which could be responsible for censorship and/or traffic manipulation.

HTTP is a protocol which transfers or exchanges data across the

internet. It does so by handling a client’s request to connect to a

server, and a server’s response to a client’s request. Every time a user

connects to a server, the user (client) sends a request through the HTTP

protocol to that server. Such requests include “HTTP headers”, which

transmit various types of information, including the user’s device

operating system and the type of browser that is being used. If Firefox

is used on Windows, for example, the “user agent header” in the HTTP

request will tell the server that a Firefox browser is being used on a

Windows operating system.

This test emulates an HTTP request towards a server, but sends HTTP

headers that have variations in capitalization. In other words, this

test sends HTTP requests which include valid, but non-canonical HTTP

headers. Such requests are sent to a backend control server which sends

back any data it receives. If OONI receives the HTTP headers exactly as

they were sent, then there is no visible presence of a “middle box” in

the network that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance

and/or traffic manipulation. If, however, such software is present in

the tested network, it will likely normalize the invalid headers that

are sent or add extra headers.

Depending on whether the HTTP headers that are sent and received from a

backend control server are the same or not, OONI is able to evaluate

whether software – which could be responsible for traffic manipulation –

is present in the tested network.

False negatives, however, could potentially occur in the hypothetical

instance that ISPs are using highly sophisticated software that is

specifically designed to not interfere with HTTP headers when it

receives them. Furthermore, the presence of a middle box is not

necessarily indicative of traffic manipulation, as they are often used

in networks for caching purposes.

Data analysis

Through its data

pipeline, OONI

processes all network measurements that it collects, including the

following types of data:

Country code

OONI by default collects the code which corresponds to the country from

which the user is running OONI Probe tests from, by automatically

searching for it based on the user’s IP address through the MaxMind

GeoIP database. The collection of

country codes is an important part of OONI’s research, as it enables

OONI to map out global network measurements and to identify where

network interferences take place.

Autonomous System Number (ASN)

OONI by default collects the Autonomous System Number (ASN) which

corresponds to the network that a user is running OONI Probe tests from.

The collection of the ASN is useful to OONI’s research because it

reveals the specific network provider (such as Vodafone) of a user. Such

information can increase transparency in regards to which network

providers are implementing censorship or other forms of network

interference.

Date and time of measurements

OONI by default collects the time and date of when tests were run. This

information helps OONI evaluate when network interferences occur and to

compare them across time.

IP addresses and other information

OONI does not deliberately collect or store users’ IP addresses. In

fact, OONI takes measures to remove users’ IP addresses from the

collected measurements, to protect its users from potential

risks.

However, OONI might unintentionally collect users’ IP addresses and

other potentially personally-identifiable information, if such

information is included in the HTTP headers or other metadata of

measurements. This, for example, can occur if the tested websites

include tracking technologies or custom content based on a user’s

network location.

Network measurements

The types of network measurements that OONI collects depend on the types

of tests that are run. Specifications about each OONI test can be viewed

through its git

repository,

and details about what collected network measurements entail can be

viewed through OONI

Explorer or through

OONI’s public list of

measurements.

The OONI pipeline processes the above types of data with the aim of deriving

meaning from the collected measurements and, specifically, in an attempt to

answer the following types of questions:

Which types of OONI tests were run?

In which countries were those tests run?

In which networks were those tests run?

When were tests run?

What types of network interference occurred?

In which countries did network interference occur?

In which networks did network interference occur?

When did network interference occur?

How did network interference occur?

To answer such questions, OONI’s pipeline is designed to process data

which is automatically sent to OONI’s measurement collector by default.

The initial processing of network measurements enables the following:

Attributing measurements to a specific country.

Attributing measurements to a specific network within a country.

Distinguishing measurements based on the specific tests that were

run for their collection.

Distinguishing between “normal” and “anomalous” measurements (the

latter indicating that a form of network tampering is

likely present).

Identifying the type of network interference based on a set of

heuristics for DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and HTTP blocking.

Identifying block pages based on a set of heuristics for

HTTP blocking.

Identifying the presence of “middle boxes” (such as Blue Coat)

within tested networks.

However, false positives and false negatives emerge within the processed

data due to a number of reasons. As explained previously (section on

“OONI network measurements”), DNS

resolvers (operated by Google or a local ISP) often provide users with

IP addresses that are closest to them geographically. While this may

appear to be a case of DNS tampering, it is actually done with the

intention of providing users with faster access to websites. Similarly,

false positives may emerge when tested websites serve different content

depending on the country that the user is connecting from, or in the

cases when websites return failures even though they are not tampered

with.

Furthermore, measurements indicating HTTP or TCP/IP blocking might

actually be due to temporary HTTP or TCP/IP failures, and may not

conclusively be a sign of network interference. It is therefore

important to test the same sets of websites across time and to

cross-correlate data, prior to reaching a conclusion on whether websites

are in fact being blocked.

Since block pages differ from country to country and sometimes even from

network to network, it is quite challenging to accurately identify them.

OONI uses a series of heuristics to try to guess if the page in question

differs from the expected control, but these heuristics can often result

in false positives. For this reason OONI only says that there is a

confirmed instance of blocking when we have manually added a known

blocking page to the list of blockpages we support.

However, this means that when a block page is not presented by the

censor we are not able to confirm with absolute certainty that blocking

is occurring. For the purpose of this study we have extended our

methodology to also take into account unusual failures that could be

triggered by the censor. In particular, we have looked at sites that

appear to fail consistently (that is in the same way) and constantly

over the testing period, therefore most likely not due to transient

networking errors.

OONI’s methodology for detecting the presence of “middle boxes” -

systems that could be responsible for censorship, surveillance and

traffic manipulation - can also present false negatives, if ISPs are

using highly sophisticated software that is specifically designed to

not interfere with HTTP headers when it receives them, or to not

trigger error messages when receiving invalid HTTP request lines. It

remains unclear though if such software is being used. Moreover, it’s

important to note that the presence of a middle box is not necessarily

indicative of censorship or traffic manipulation, as such systems are

often used in networks for caching purposes.

Upon collection of more network measurements, OONI continues to develop

its data analysis heuristics, based on which it attempts to accurately

identify censorship events.

Findings

As part of this study, 38,598 network

measurements were

collected on a daily basis from a local vantage point (MTN) in Zambia,

starting on the day of the general elections (11th August 2016) and

concluding twelve days later. Such network measurements were collected

via OONI’s software distribution for Raspberry

Pis, which is

designed to examine whether a set of URLs are blocked (and if so, how),

and whether systems (“middle boxes”) that could be responsible for

censorship, surveillance and traffic manipulation are used within a

tested network.

Upon analysis of the collected data, the

findings illustrate

that 10 different websites were consistently inaccessible during the

testing period based on DNS tampering, TCP/IP blocking, and various

forms of HTTP blocking. These findings are summarized in the table

below:

| Tested site | DNS | HTTP-diff | HTTP-failure | TCP/IP blocking | CTRL failure rate |

|---|

| drugs-forum.com | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.0% |

| wzo.org.il | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.0% |

| cidh.org | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.06% |

| pof.com | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.36% |

| gayromeo.com | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 2.9% |

| pinterest.com | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 7.12% |

| weforum.org | 1.0 | 0.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 | 7.11% |

| pornhub.com | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 13.9% |

| online-dating.org | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17.57% |

| proxyweb.net | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 65.3% |

The failure rate column in the table above shows the percentage of

failed requests to the sites in question from OONI’s control vantage

point from 2016-07-01 to 2016-09-01. Since no block pages were found in

testing the accessibility of sites in Zambia, OONI extended its

methodology to take into account the failure rate of sites during the

testing period compared to the overall failure rate from control vantage

points. In short, OONI considers a website to be blocked if connections

to it consistently fail across the testing period and if it exhibits a

low overall failure rate from control vantage points.

Based on this methodology, sites with low failure rates (from control

vantage points) - such as drugs-forum.com, cidh.org, and pof.com - are

more likely to have been blocked during the testing period than other

sites, such as proxyweb.net, which present higher failure rates.

The

inaccessibility

of gayromeo.com, an online dating website for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual,

and Transgender (LGBT) communities around the world, might potentially

be attributed to the prohibition of same-sex activity in Zambia.

Sections 155 through 157 of Zambia’s Penal

Code

prohibit homosexual activity and impose a penalty of up to fourteen

years of imprisonment. Similarly, both online-dating.org and pof.com

may have been blocked for supporting homosexual dating, though

online-dating.org also presents a high level of global failures.

Pornography is

prohibited

in Zambia under Article 102 of Part XV (“Cyber crime”) of the Electronic

Communications and Transactions Act 2009, which might explain why

pornhub.com was

found

to be inaccessible throughout the testing period. It’s worth pointing

out, however, that other pornographic websites were found accessible

during the same testing period.

The inaccessibility of other websites appears to be less justifiable.

The World Economic Forum’s website, for

example, was

found

to be consistently inaccessible based on DNS tampering and HTTP

failures, but the motivation or legal justification behind this remains

unclear. Quite similarly, it also remains unclear why the

website of the Organization of American States

(OAS), which is responsible for the promotion and protection of human

rights in America, was found to be

inaccessible

in Zambia during the 2016 election period. While the website of the

World Economic Forum also presented a failure rate of about 7%

(indicating that it might not actually have been blocked by Zambian

ISPs), the website of the OAS presented a failure rate of less than 1%,

indicating that it might have been blocked.

Other websites that raise questions include the

website

of the World Zionist Organization, which aims at establishing a legally

assured home in Palestine for the Jewish people. Interestingly enough,

this website presented 0% failure rates from control vantage points, but

connections to it failed consistently throughout the testing period.

It’s unclear though if this is due to TCP/IP blocking implemented by

Zambia’s MTN, or if the website itself rejected connections coming from

Zambia. Photo-sharing platform Pinterest also

appeared

to be inaccessible, presenting HTTP failures consistently across the

testing period, but the website’s failure rates (around 7%) indicate

that this might not actually be a case of censorship.

Multiple other websites, beyond the ones included in the above table,

also presented signs of network interference. However, upon examining

these websites across the testing period, connections to them appeared

to be successful in most cases, indicating that many of the cases of

network interference were likely false positives due to transient

failures.

On a positive note, the websites of Zambia’s opposition members and the

news outlets (such as zambiawatchdog.com/) that were previously censored

between 2013 and 2014 were not

found to be blocked

during this testing period. Out of a total of 1,303 websites that were

tested for censorship in Zambia, only 10 of those websites presented

signs of network interference.

The above cases, as detected through the use of OONI’s

software, indicate the

presence of censorship equipment within the tested network. However,

OONI’s HTTP invalid request

line

and HTTP header field

manipulation

tests did not detect the fingerprints of such equipment, preventing

the identification of the specific types of equipment being used.

Acknowledgement of limitations

The findings of this study present various limitations, and do not

necessarily reflect a comprehensive view of internet censorship in

Zambia during the 2016 general election period. The first limitation is

associated with the testing period, which started on the day of the

general elections (11th August 2016) and concluded only twelve days

later, without covering the pre-election period when other censorship

events might have occurred. This limitation is associated with safety

concerns and challenges in regards to probe deployment.

Another limitation to this study is the amount and type of URLs that

were tested for censorship. As mentioned in the methodology section of

this report (“Creating a Zambian test list”), the criteria for selecting

URLs that are relevant to Zambia were biased. This URL selection bias

was influenced by the core objective of this study, which sought to

examine whether websites reflecting criticism towards the ruling party

were blocked. Furthermore, while a total of 1,303 different URLs were

tested for censorship as part of this study, not all the URLs on the

internet were tested, indicating the possibility that other websites not

included in test lists might have been blocked.

Furthermore, this study was limited to one local network vantage point

(MTN Zambia) and therefore does not include measurements from other

networks, where more and/or other censorship events might have occurred.

This limitation is associated to safety concerns and challenges in terms

of engaging volunteers in Zambia to run tests.

Finally, the heuristics used as part of OONI’s methodology present

limitations. This is due to the fact that many false positives and false

negatives occur within collected data (as explained in the methodology

section of this report), limiting OONI’s ability to confirm cases of

censorship with confidence in many cases. Moreover, OONI’s heuristics

are limited to a sample of censorship equipment fingerprints, limiting

the ability to identify other types of equipment that may have been used

within tested networks.

Conclusion

This study highlights the possibility of DNS, TCP/IP and HTTP

blocking of 10

different websites during Zambia’s 2016 general election period. As no

block pages were detected, none of these cases can be confirmed with

confidence.

Sites that support LGBT dating and pornography were found to be

inaccessible throughout the testing period. Under the provisions of

Zambia’s Penal

Code

and Electronic Communications and Transactions Act

2009,

the blocking of such sites can potentially be legally justified.

Pinterest was also

found

to be inaccessible, as well as the websites of the World Economic Forum, the

Organization of American States (OAS) and the World Zionist Organization.

However, the motivation and legal justification behind these possible

censorship events remains unclear. On a positive note, the websites of Zambia’s

opposition members and the news outlets that were previously censored between

2013 and 2014 were not found to be blocked during this testing period.

OONI and the CIPIT

encourage transparency around internet controls, particularly during election

periods, to help enhance the safeguard of human rights and democratic

processes.